From above

Looking like an astronaut

Our world is, in fact, a small, fragile blue marble in an immeasurably vast universe. To truly see that, you have to look like an astronaut—from a new dimension.

‘I brought my sharpest right angle into violent collision with the Stranger and pressed against him with a force that would have crushed any ordinary Circle. Yet I felt him slowly but surely slip away from me. Not that he dodged left or right, but somehow, he moved out of the world and disappeared into nothingness.’

This passage comes from the curious but beautiful book Flatland by Edwin Abbott Abbott—a mathematician and also a satirical novelist, published in 1884. The speaker is A. Square, a square who lives in a flat world along with lines, triangles, and circles. At least, that’s what he thinks. One day, however, a sphere comes to visit him and tells him that there is a third dimension. Initially, A. Square reacts with skepticism, and then—as described above—he attacks the sphere. It’s only when he’s lifted upward and views his land from a new perspective that he realizes the world is entirely different from what he had always believed.

What A. Square experiences here is known as the overview effect—the emotional shock that occurs when you see something from a distance for the first time. It’s especially familiar to astronauts who suddenly see Earth from space. They abruptly realize that our vast world is actually a small, fragile blue marble in a boundless universe. Why is this effect so powerful for otherwise level-headed astronauts? Because not only do they go to a place no other human has gone, they also—like A. Square—enter, in a sense, a new dimension.

A Step Back

But first, let’s return to the inhabited world. We’ve all experienced how taking a step back can help give us a clearer view. When you look at a large painting, you step back to take in the whole image. And even if ten motorbikes with cameras are weaving through the cyclists, the Tour de France remains hard to follow without the helicopter footage.

However, taking a step back doesn’t always bring clarity. If you’re too close to a painting and just step sideways, your view won’t improve. And when the Tour caravan enters the Champs-Élysées in Paris, the TV helicopter doesn’t fly off to the Eiffel Tower for a more distant view. You have to move in the right direction, or you lose the image entirely.

The Right Direction

From a physics point of view, that “right direction” is another dimension. Cyclists move forward and sideways. To gain a clear view of that, a helicopter has to move in a different dimension—straight up. The same was true for the sphere that lifted A. Square upward. A painting is also two-dimensional, but in width and height. To get a proper overview, you shouldn’t move sideways or up, but backward.

But what if you want to gain an overview of a three-dimensional space? Not a painting, but a sculpture? Or if you want to study the whole world—or even the entire universe? Following the same logic as with the painting and the cycling race, you would gain clarity by moving into another, fourth dimension. Is that possible? Technically, time is a fourth dimension, but we can’t move through it freely like we can in space. You can’t just look at a situation from the year 1969 or 2069. As far as we know, there’s no fourth spatial dimension we can move through. So unless a “hypersphere” suddenly appears and drags us into a new direction—however reluctantly—we’ll have to make do with the three dimensions we’ve got.

'We are trapped in a more or less two-dimensional world. Not that the Earth is flat, but our living environment is.'

A New Perspective on the Future

Because we can’t enter another dimension, our perspective on three-dimensional things is never perfect. It gets even worse when we’re trapped inside the thing we want to see. Take our own galaxy, for instance. We know exactly what many other galaxies look like—but not our own Milky Way. It’s likely a spiral, as most others are, but the precise pattern remains unclear. Because we’re inside the Milky Way, we can’t see it properly—just as you can’t see your own face without a mirror.

Smaller three-dimensional objects can be observed well from a distance. If you move around a sculpture, you can usually get a good view of it. But even then, you’re not really entering another dimension. It’s that combination—of stepping outside and moving into a new dimension—that’s essential for seeing the whole picture in a single glance.

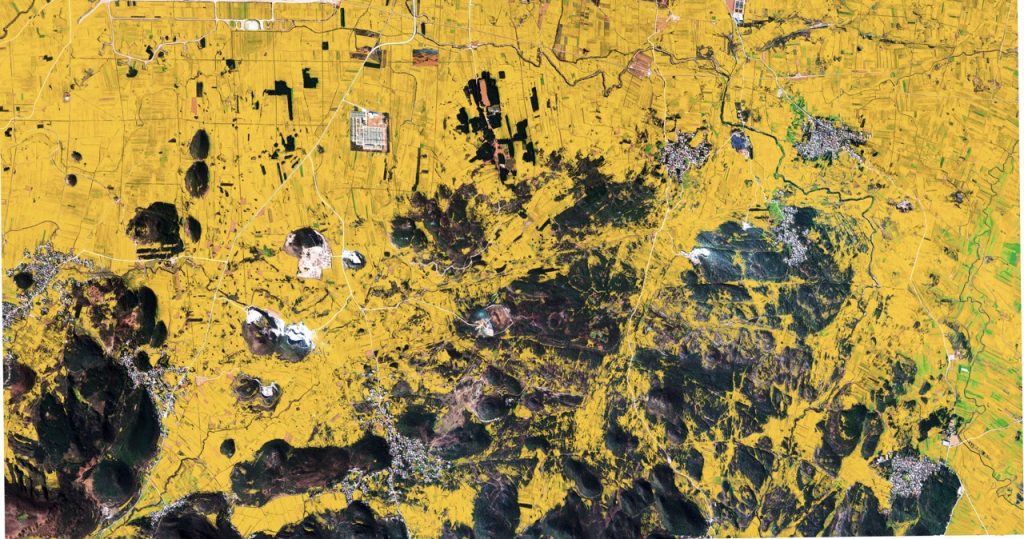

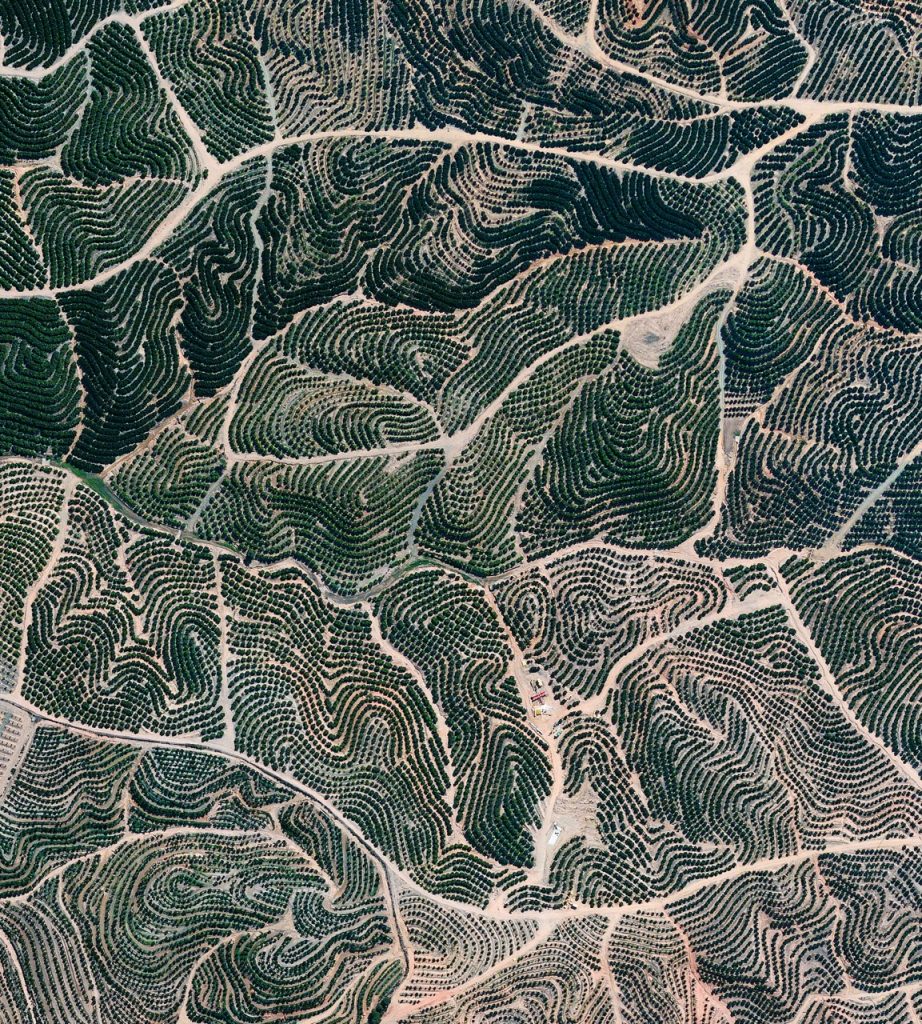

And you can achieve that combination—by taking a step back from the entire world. The Earth, after all, isn’t really three-dimensional. Not that I’m claiming the Earth is flat—though it’s alarming how many still believe this—but our living environment effectively is. We live almost entirely on the surface, and two coordinates (like longitude and latitude) are usually enough to specify where we are. We move kilometers every day from front to back and side to side, but when it comes to height, we usually only gain a few meters using stairs or elevators.

So when we do go a little higher, the effect is immediate. On top of a hundred-meter tower, we marvel at how tiny people look—yet a goalkeeper on a football field is never surprised by how small the other keeper looks across the pitch. In a plane, we’re completely awestruck by the view, even though we’re only about ten kilometers up—which is a distance you could drive in five minutes. So, compared to the other two, we barely use the third dimension. Our world isn’t quite Flatland, but I wouldn’t call it fully three-dimensional either.

Beautiful but Fragile

So there’s a lot of ground to gain in the third dimension. So far, only astronauts have managed to venture a bit further. They were the first to realize we’re trapped in a small, two-and-a-bit-dimensional world. As Apollo 8 astronaut William Anders put it: “We came all this way to explore the Moon, and the most important thing we discovered was the Earth.”

Our planet turns out to be breathtakingly beautiful—but also fragile. The true impact of deforestation, for example, is much more visible from space than from the ground, where the lack of trees makes it hard to see the scale of the loss. A new perspective on Earth also brings a new perspective on our future.

Through their photographs, astronauts help pass the overview effect on to others. So we all get carried along, just a little, into a new dimension—not a mysterious fourth one, but the third dimension. The dimension we use so little, but which is essential to keeping our rapidly changing world even just a little bit comprehensible.