The Secret to a Longer, Happier Life: Art

How the Arts Transform Us

New groundbreaking research by Susan Magsamen and Ivy Ross, published in their book Your Brain on Art, confirms what we have long suspected: art proves to be just as essential to our survival as sleep, movement and nutrition. For See All This, they reveal the key findings of their research.

‘Humanity began with firelight,’ evolutionary biologist Edward O. Wilson told us before his death in 2021. ‘Our lives as we know them come courtesy of lightning.’ Arcs of electricity six times hotter than the surface of the sun sparked trees and brush to flames on the African savanna where early Homo erectus and Homo sapiens captured this magic and carried it with them from place to place. Our prehistoric ancestors learned to harness wildfires into controlled campfires, bringing them back to shelters and camps.

During the day, language developed to address the basic daily needs of the group, from the logistics of tracking animals to caring for children and preparing food. At night, though, something remarkable happened. Fires were built, wood crackled into flame, and woodsmoke, heady and fragrant, filled the air. A honeyed glow warmed faces and illuminated the dark for the first time, offering warmth and protection from predators. So began the lasting human desire to make a circle, stare into the flickering fire, and commune.

The pragmatism of the day made way for the mystery and evocative nature of night, as fire fostered new forms of coming together. We created stories. We sang. We danced. We drew. We developed myths and metaphors that passed on the moral and ethical values of the group. We celebrated and we mourned.

Through the centuries, these creative expressions forged layers of meaning-making. Tribes around the world formed, and a sense of belonging emerged between individuals, families and groups. It was through these repetitive creative acts, that humans developed strong social bonds, created trusting relationships and a collective feeling of transcendence and communal need emerged.

Fire sparked the birth of community. More than 250 million years of evolution have favored social development and the core imperative to thrive in community by honing our unique ability to creatively share our thoughts, ideas, and emotions with one another. Today, there are still over 5,000 indigenous tribes on the planet, many of whom don’t have a word for art because it is simply entrenched in how they live.

Since the industrial revolution, we have been optimizing for productivity, and with that we have put fundamental human needs aside, because the arts are not only our birthright: science is discovering that we are evolutionarily and physiologically wired for them. The arts turn out to be as essential to our survival as sleep, exercise, and nutrition.

what artists already knew

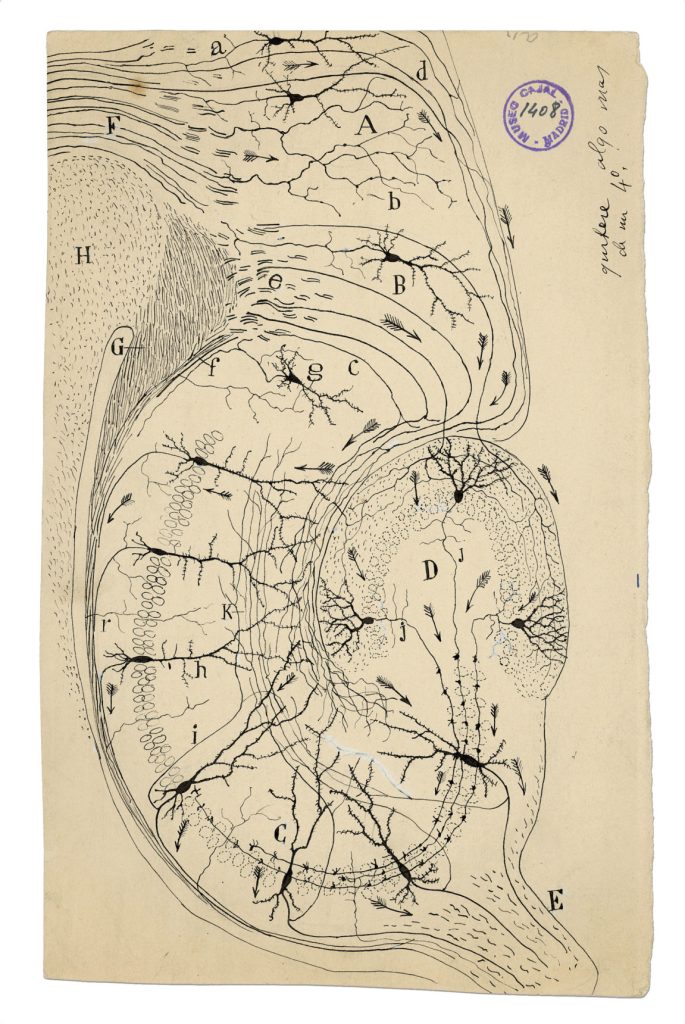

Over the last 25 years, technology has enabled us to non-invasively get inside our head, and researchers are catching up with what artists have always intuitively known. Research is confirming that arts and aesthetic experiences alter a complex physiological network of interconnected neurological and biological systems including cognition, immune and endocrine, circulatory, respiratory, reward and motor systems – to name just a few.

Many of these discoveries have been made through neuroaesthetics, an emerging interdisciplinary field. The goal is to understand how the arts and aesthetic experiences measurably impact our brains, bodies and behavior, and how this knowledge can be translated into practice in health and wellbeing.

A key to understanding the transformative power of the arts and aesthetics is found through our sensory systems. We literally bring the world in through our senses and these mechanisms are fascinating.

Smell is one of the oldest senses in terms of human evolution. Your nose can detect 1 trillion odors with over 400 types of scent receptors whose cells are renewed every thirty to sixty days. In fact, your sense of smell is so good that you can identify some scents better than a dog can.

Microscopic molecules released by substances around you stimulate your scent receptors. They enter your nose and dissolve in mucus within a membrane called the olfactory epithelium, located a few inches up the nasal cavity from the nostrils. From here, neurons, or nerve cells, which are the fundamental components of your brain and nervous system, send axons, which are long nerve fibers, to the main olfactory bulb. Once there, they connect with cells that detect distinct features of the scent.

Like scent, taste is also a chemical sense: The foods you eat trigger your 10,000-plus taste buds, generating electrical signals that travel from your mouth to an area of the brain called the gustatory cortex. This part of the brain is also believed to process visceral and emotional experiences, which helps to explain how it is that taste is among the most effective sensations for encoding memory.

Our ability to hear is intricate and precise. Sound from the outside world moves into the ear canal, causing the eardrum to vibrate. These sound waves travel through the ossicles to the cochlea and cause the fluid in the cochlea to move like ocean waves. There are thousands of small hair cells inside of the cochlea, and when the fluid moves, these cells are activated, sending messages to the auditory nerve, which then sends messages to the brain. The auditory cortex, also located in the temporal lobe, sits behind your ears, where memory and perception also occur. Music is the most researched art form.

Our ability to see requires us to process light through a complex system. Your eyes work similarly to a camera. What you see is converted into electrical signals by photoreceptors. The optic nerve then sends these signals to the occipital lobe in the back of the brain and converts them into what you see. It’s here that we perceive, recognize, and appreciate objects, and neuroscientists are discovering that it is one part of this lobe – the lateral occipital area – that contributes to how we process and create aesthetic appreciation of art.

Touch is one of the more powerful cognitive communication vehicles. It was one of our first sensory systems to evolve. Your fingers, hands, toes, feet, and skin are extraordinarily sensitive, picking up minute cues that trigger physiological and psychological responses. In each of your fingers, you have more than 3,000 nerve endings that are constantly taking in physical sensation. Touch receptors in your skin connect to neurons in the spinal cord by way of sensory nerves that reach the thalamus in the middle of the head on top of the brain stem.

We share our feelings and emotions through the simple act of holding a hand or sharing a hug. Touch rapidly changes our neurobiology and mental states of mind by releasing the neurotransmitter oxytocin, which is also attributed to feelings of trust, generosity, compassion, and lowered anxiety.

always making new connections

Your smell, taste, vision, hearing, and touch produce biological reactions at staggering speeds. Hearing is registered in about 3 milliseconds. Touch can register in the brain within 50 milliseconds. Your entire body, not just your brain, takes in the world, yet much of this is outside of your awareness. Cognitive neuroscientists believe we’re conscious of only about 5 percent of our mental activity. The rest of your experience – physically, emotionally, sensorially – lives below what you are actually thinking.

Your brain is processing stimuli constantly, like a sponge, absorbing millions of sensory signals. But not all of the information that your brain is processing reaches your consciousness. You can’t process all the sensory stimuli that you are exposed to every day, but the most salient information that enters your body has an unlimited capacity to change your biology and behavior. Your brain pays attention to what is important to you either because it is practical or emotionally relevant. Turns out, the arts and aesthetics are some of the most salient experiences we have.

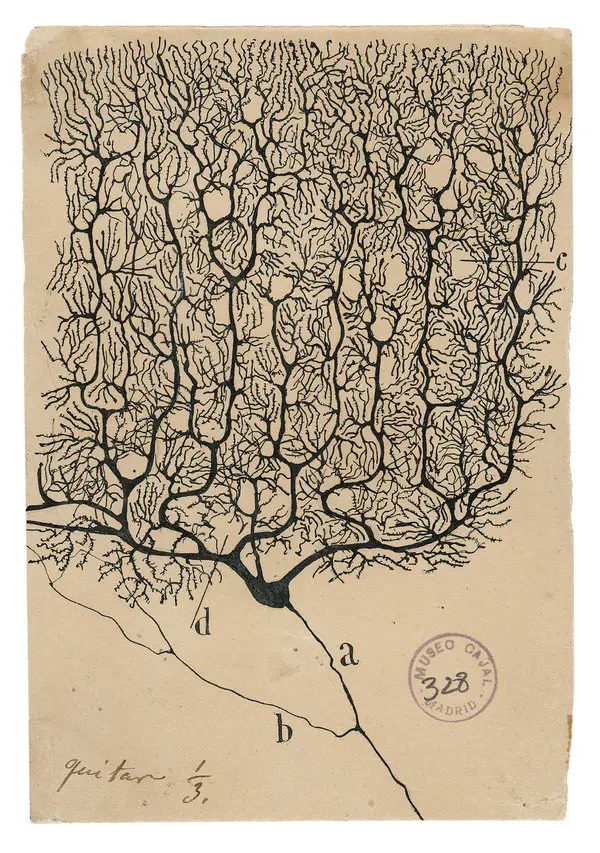

These arts and aesthetic experiences ignite your brain’s neuroplasticity. Each of us are born with 100 billion neurons that connect at a synaptic level. You have quadrillions of these connections in your brain, creating endless neuropathways. These pathways underlie your body movements, emotions, memory – basically, everything you do. When you are making a memory or learning something you are actually making some synaptic connections stronger and some weaker through the saliency of your experiences. And that is neuroplasticity.

You are always making new connections and pruning old synapses. This is why by continually putting yourself in new places and experiences, like going to museums and galleries, and performing and visual arts – including viewing beautiful publications such as See All This changes your brain in positive ways.

becoming you

Becoming aware of what you like and don’t like, and better understanding how you are influenced, informed, and changed by arts encounters, creates opportunities for you to apply your own perceptual preferences to almost every area of your life. Using arts and aesthetics in this personalized way is so powerful because of your default mode network.

The default mode network is now believed to be where the neurological basis for the self is housed. Your responses to the arts and aesthetics are as individual as the geometry of a snowflake. The sonatas of Mozart or the sounds of traditional Portuguese fado music might transport some, while others feel uplifted by the Persian calligraphy of Mir Ali Tabrizi or the smell of ink made from henna. Still others get into the flow by being immersed in a film or reading a poem. One person’s cacophony is another person’s symphony. And your perception is your reality.

Your experiences with the arts and aesthetics are so singular because your brain-connectivity patterns are distinctive. Through your experiences, billions of new synapses form in your brain and these conduits build a repository of stored knowledge and responses as unique as your fingerprints. No one else, not a single person on this planet, has your exact brain.

microdosing Aesthetics

Many of us tend to think of the arts as either entertainment or as an escape. A luxury of some kind. But they are so much more. Beyond prevention and brain health support, they can help address serious physical and mental health issues, with remarkable results. And they can help you learn, flourish and build community.

Around the world, doctors are prescribing museum visits. Schools are bringing music, studio art and performing arts back to enhance learning. And because research shows that sensory-rich environments help us learn faster and retain information better, workplaces, galleries and public spaces are being reimagined and redesigned with both function and feeling in mind.

We each have the agency to take actions that move us toward experiences that give us meaning and purpose and help us heal, learn, and thrive. It is in this way that simply daily habits become our lives. Simple, quick, accessible ‘acts of art’ can enhance your life.

Already we see a rise in microdosing of aesthetics as people use specific scents to relieve stress, calibrate light sources to adjust energy levels, and use specific tones of sound to alleviate anxiety. In the same way you might exercise to lower cholesterol and increase serotonin in the brain, just twenty minutes of doodling or humming can provide immediate support for your physical and mental state. Immersing yourself in aesthetic experiences from being in nature to visiting a gallery, lowers cortisol, the stress hormone. Playing music increases synapses and gray matter in the brain which helps support cognitive skills, while just one or more artist experiences a month, as a marker or a beholder, can extend your life by ten years. And researchers have debunked a huge myth, which is that you don’t have to be a skilled artist to have a significant impact on your health and wellbeing.

We invite you to build your aesthetic mindset. Engage your natural curiosity. Try more playful explorations, suspend judgment and simply experiment. Open yourself up to the sensorial experiences throughout your day. And be a maker and a beholder with even more intention.

It’s been said, the world is full of magic things, patiently waiting for our senses to grow sharper.

about the artist

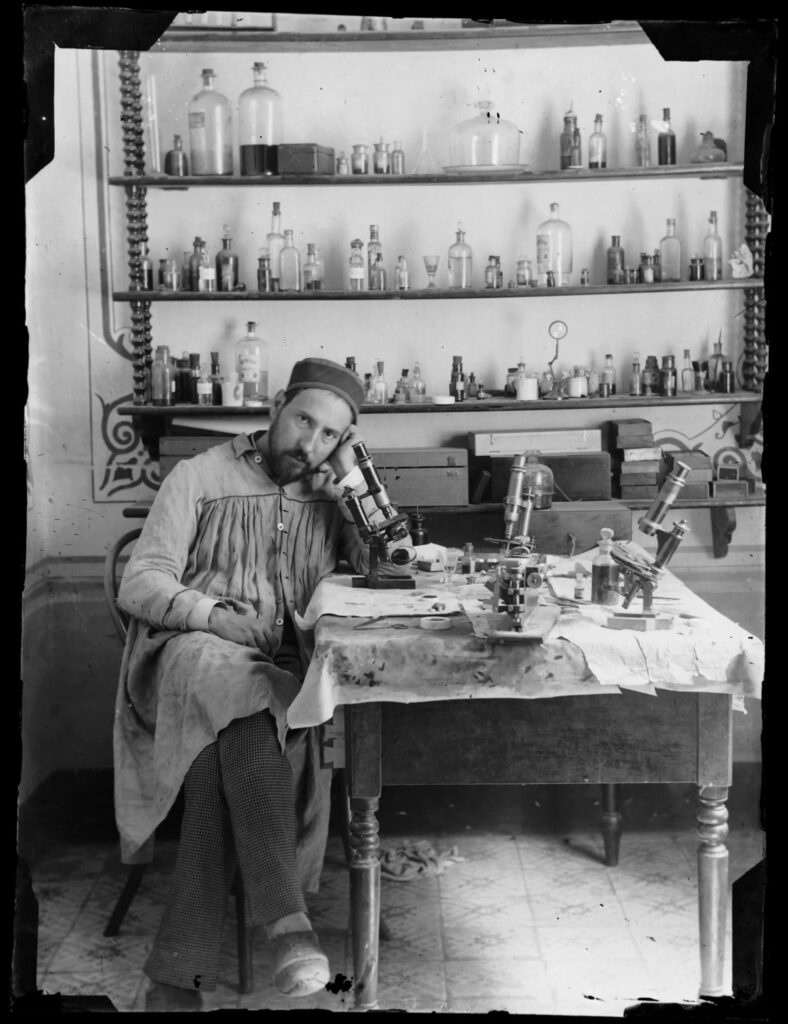

‘As long as our brain remains a mystery, the universe, a reflection of the brain’s structure, will also remain a mystery.’

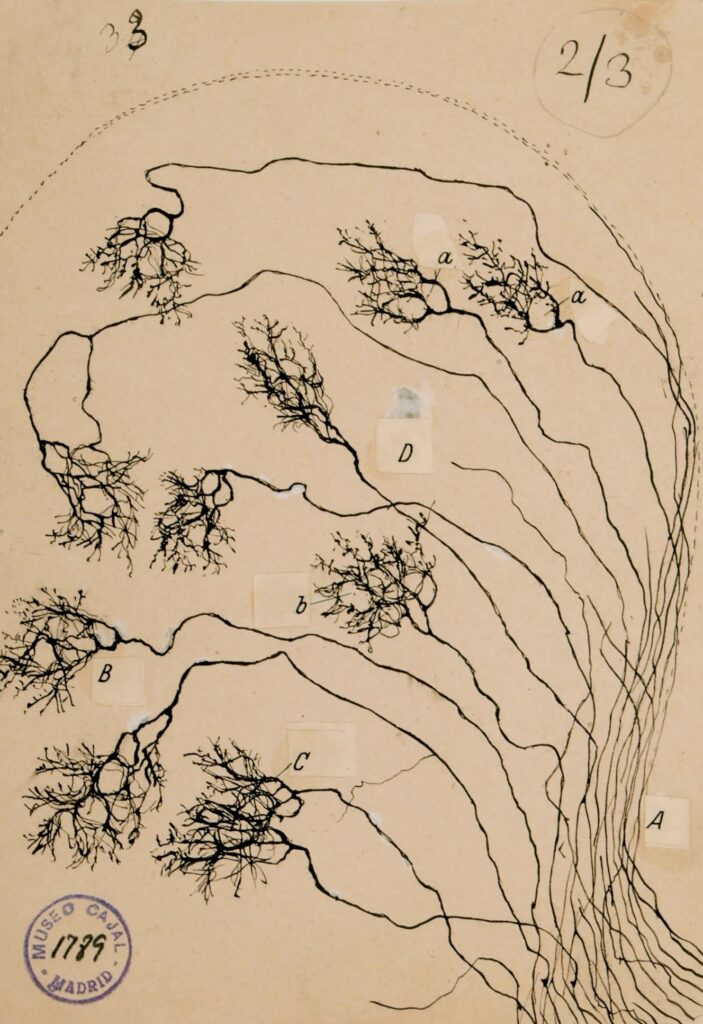

Santiago Ramón y Cajal (1852-1934) was an artist, photographer, physician, bodybuilder, chess player and publisher, but above all a pioneer of modern neuroscience. Although he himself would have preferred to spend his hours in the studio, his father insisted that he become a doctor. He went on to devote himself to the fascinating anatomy of the brain, translating his discoveries into spectacular drawings.