Just not perfect

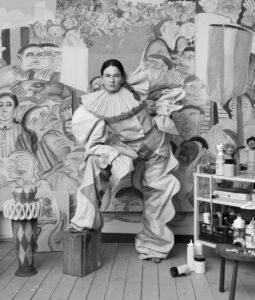

Callum Innes

It is sometimes said of Callum Innes that he does not actually paint, but “unpaints”. A conversation about paint, turpentine and dots that are just off-centre.

Anyone who wants to understand Callum Innes’ paintings should look for the unevenness. In Innes’ paintings, we often see multiple evenly coloured, quadrangular areas of colour. Perfect, geometric shapes, it seems at first. Only when you carefully scan the edges of those colour areas do you see the frayed edges, the unevenness – and thus the key to the canvases’ genesis.

Anyone talking to Callum Innes (Edinburgh, 1962) talks first and foremost about his technique, his way of working. About paint and putty knives, the quality of paper and canvas, about turpentine and dots that are just off-centre. Innes likes to talk about how a work is created, the stages he goes through. And those irregularities, Innes says, are created as follows: on the canvas, he applies one colour, with a broad brush. Then he partly paints a second colour over it. While the work is still wet, he then removes most of the paint again, with a sponge or a large putty knife. Which colours he has used can then only be seen at the edges, where an irregular stripe of the original paint peeks out from under the coloured surface. The end result, the combination of the two mixed and partly erased colours, is different each time. ‘What the two colours do to each other is always a surprise. It can’t be predicted. That’s what I find interesting.’

The act of painting, of adding and then taking away, of “doing and stripping,” is essential to Innes. ‘Unpainting,’ some critics call it. But the Scottish artist cannot agree with that. After all, by first applying the paint and then partly removing it again, something new is created: the paper or canvas changes under the influence of the paint.

Innes is brief about the meaning of his abstract paintings: the viewer must discover it for himself. He prefers to leave out titles altogether; sometimes he uses a short, factual description of the technique, such as “Exposed,” a term from photography, or of the color of paint he uses, such as Carmine Light / Windsor Yellow or Opera Rose / Gold Green. Sometimes a painting is given only a number: Untitled No. 19. Innes: “As soon as you give a painting a title, Landscape for example, as a viewer you start looking for recognition. I don’t want to predetermine the way you can look at the work. As a viewer, you can decide for yourself what you see in it.’

'What those two colors do to each other is always a surprise. It can't be predicted. That's what I find interesting.'

Coincidence often plays a role in Innes’ work. Although he now employs several assistants to prepare papers and canvases, he paints everything himself. Sometimes he lets drops of turpentine run down the sides of an oil painting so that the colors blend together and form shaky streaks. In the Exposed series, paintings with four or five planes next to and under each other, he has always made one of the edges between the planes just barely straight. Your eye automatically corrects that “mistake”. This is even more extreme in Isolated Form (Cadmium Red Deep) from 1995. We see a very small, white square, exactly in the middle of a large, red plane. At least, so it seems. Because if you look more closely, you see that the dot is just off center. Innes: “Such a small shift makes such a simple image complex; it keeps it exciting.