Los Angeles, lust and light

David Hockney 80

All David Hockney wanted as a child was to draw. The simple British boy left for California. He grew to Sunshine Superman ‘Painters make the world incredibly exciting.’

It was the most successful crowd-puller in the history of Tate Britain: the retrospective exhibition of David Hockney, organized by the museum in collaboration with the Centre Pompidou in Paris and the Metropolitan Museum in New York. Even before the opening this past February, 35,000 tickets had already been sold. Weekend opening hours were extended until 10 p.m., and by the end of May, the Tate was even open until midnight for the first time in its history. Director Alex Farquharson, ‘delighted’ by the overwhelming response, wrote in a press release: ‘David is without a doubt one of the greatest living British artists. His influence on art and culture is immeasurable. We expect this to be one of the most visited exhibitions in the museum’s history.’

The occasion is Hockney’s eightieth birthday on July 9, and the traveling exhibition is the most extensive retrospective of his work to date. Curators assembled over one hundred works, created over a period of nearly sixty years. There are early paintings that hover between figurative and abstract—which, according to The Guardian, belong to his best work; of course, the iconic California swimming pools with their intense acrylic colors; the Polaroid collages; the iPad drawings; the stunning portraits; and Hockney’s recent landscape works, which, despite their dazzling colors, carry a hint of melancholy.

The Centre Pompidou, which is staging an even larger exhibition with 162 works starting on June 21, also expects record visitor numbers, says head of communications Anne-Marie Pereira from Paris.

JOY AND EXUBERANCE

It took years to gather everything for the traveling exhibition. However varied Hockney’s oeuvre may be, however versatile the techniques, however dizzying his output, the common thread in his work is what Hockney himself calls perspective: how we look at the world, with what eyes, with what instruments, and how that gaze influences the image that is created.

About fifteen years ago, after years of experimenting with different techniques, the artist arrived at an almost humanistic conclusion: that the hand that draws will always win out over the camera or the computer. Those blossoms in the rolling landscape of East Yorkshire, he once remarked as his assistant was photographing them on a spring day, looked far more magnificent in real life than in the photos. The camera simply couldn’t capture their joy and exuberance. The psychology behind the human eye, and the drawing hand, could.

“What a boring world photography actually produces,” Hockney thought, after being granted early-morning access to the breathtaking Matisse/Picasso exhibition at Tate Modern in August 2002, together with painters Lucian Freud and Frank Auerbach. While walking toward the exit, he encountered a series of photographic works. What was that so-called “realism” worth? “Matisse and Picasso made the world unbelievably exciting. Photography makes it all very, very flat.”

“Has photography made painting obsolete, as is so often claimed in art circles?”

As far as Hockney was concerned: “Far from it!

ANTI-ESTABLISHMENT

You could safely say that Hockney was successful from the moment he, as a 23-year-old student at the Royal College of Art in London, was selected to participate in the Young Contemporaries exhibition, which annually showcased the best work of young British artists. The press was full of praise—not only for the new movement that came to be known as the beginning of British pop art, and which critics saw as a sign that post-war British art was finally moving on from the drab Kitchen Sink realism to liveliness, hope, and flair—but especially for the work of the young Hockney, who exhibited paintings that explored his homosexuality, featuring texts on the canvas by poets Walt Whitman and Cavafy, who openly celebrated love for the male body.

Photographer Cecil Beaton sought out the student after the exhibition and was among the first to buy one of Hockney’s works.

It had been clear long before that Hockney possessed exceptional talent. He was drawing before he could even go to school—on the edges of newspapers, with white chalk on the linoleum floor in the kitchen, in the flyleaves of hymn books in the Methodist church.

David was the fourth child of Methodist parents—bright, progressive people who might have gone far in different times, but who, during and after the Second World War, struggled to get by in the northern textile city of Bradford with five children. In the summer, the children foraged for wild berries and leaves to add to their salads, and on Sundays they took turns inviting a friend over, when Mrs. Hockney and her daughter Margaret would bake cakes and pies. Together with their father, David and his brother built a tandem bicycle that would carry the boys on light summer mornings to York or Leeds—four hours cycling there, four hours back.

It was a modest life, but not at all narrow-minded. Hockney’s father, Kenneth, was a radical pacifist, a teetotaler, and a vegetarian who refused to enlist or work for any company that profited from the war effort. To earn money, he opened a stroller repair shop. There, David developed a fascination with manual work. “Such a marvellous thing, to dip a brush into paint,” he told his biographer Christopher Simon Sykes.

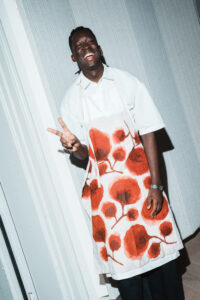

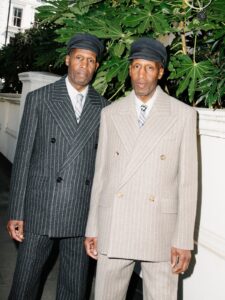

From his father, David inherited not only his anarchistic streak, but also a love of dandyish clothing. Hockney, like his father before him, has always dressed carefully and somewhat flamboyantly. In 2005, Christopher Bailey, creative director at Burberry, based the entire men’s spring collection on Hockney’s style. In 2012, fashion designer Vivienne Westwood named a checked jacket after the artist.

It is likely that the loving devotion of his parents—despite their at times downright impoverished circumstances—is the reason why Hockney has remained so unpretentious and anti-establishment, despite his fame and long-lasting friendships with well-known artists and writers. He has always sought—and still seeks—the company of people who prefer to mock self-importance rather than embody it.

ABSOLUTE DEDICATION

Young Hockney was a bright student, and at the age of ten, he earned a coveted scholarship to a prestigious academic preparatory school: Bradford Grammar School, one of the oldest in the country. But when he realized that art was a negligible part of the curriculum, he deliberately failed his exams—to the astonishment of his teachers—so that he could be transferred to the section for less gifted pupils, who did receive art lessons. “Am no good at science,” wrote the ten-year-old, who was actually among the brightest in his class, “but can draw.” That absolute dedication to art—or “work,” as he calls it—has stayed with him his entire life. He sketched wherever he went, in watercolor or pen: at Lake Como, on a rainy Parisian bridge, in the Spanish Alhambra, in a courtyard in Seville, or at a Chinese airport—dark green palms in simple strokes, blue mountains behind them. To this day, Hockney works from morning to night, seven days a week. His life is simple, as he has often told journalists. He gets up at eight, goes to bed at nine, and works all the hours in between.

Friends and colleagues, in Christopher Simon Sykes’ two-part biography A Rake’s Progress, speak of the unique mix of humility, determination, and boldness that the young artist displayed in the early years of his fame. He was shy, looked at his feet when he spoke, and had a heavy northern accent. His art dealer, John Kasmin (b. 1934), recalls the first time he took 24-year-old Hockney—already laden with art prizes—out to lunch to discuss a contract. At Hockney’s suggestion, they went to his favorite restaurant, Vega, near Leicester Square. Kasmin, used to lavish meals in upscale restaurants, could hardly believe the modest bill when it came. Noticing Kasmin staring at it, Hockney asked nervously, “Oh Mr. Kasmin, is it too much?”

But he had nerve too—he unabashedly painted themes of homosexuality and, beneath his modest demeanor, carried an unshakable conviction about what he wanted to do with his life. He also loved playing the clown; he was cheeky, old friends say, and full of bravado.

GOLDEN DAYS, BLOND HAIR

In the late 1960s, Hockney moved from London to Los Angeles. Unlike the British capital, it was “sexy, sunny, and spacey.” These were golden days for the California art scene. The painter met Ed Ruscha and Dennis Hopper, and became close friends with British writers Christopher Isherwood and Stephen Spender. Hockney bleached his hair—he thought it looked more American—and got himself a signature owl-shaped pair of glasses to appear more professorial for a teaching post at the University of Iowa.

During those years, Hockney traveled back and forth across the United States with friends and beautiful lovers, from New Orleans to Colorado, Iowa, New York, and back to Hollywood. In New York, his first solo exhibition was an instant sell-out. Among the guests were Paul Newman, Diana Vreeland, Andy Warhol, and The Velvet Underground. Hockney had made it, and in 1970—at just 33 years old—he was honored with a retrospective at London’s Whitechapel Gallery.

From this era come Hockney’s famous “swimming pools.” In these pastel-hued works, now celebrated worldwide, he not only aimed to capture the glossy spirit of California but also to solve a formal problem: how to depict water. “It can be any color, it moves, it has no visual description,” he said. The most famous, though not necessarily the best, of these works is A Bigger Splash (1967)—a title that has since been repeatedly used to symbolize the scale and fame of Hockney’s life and work.

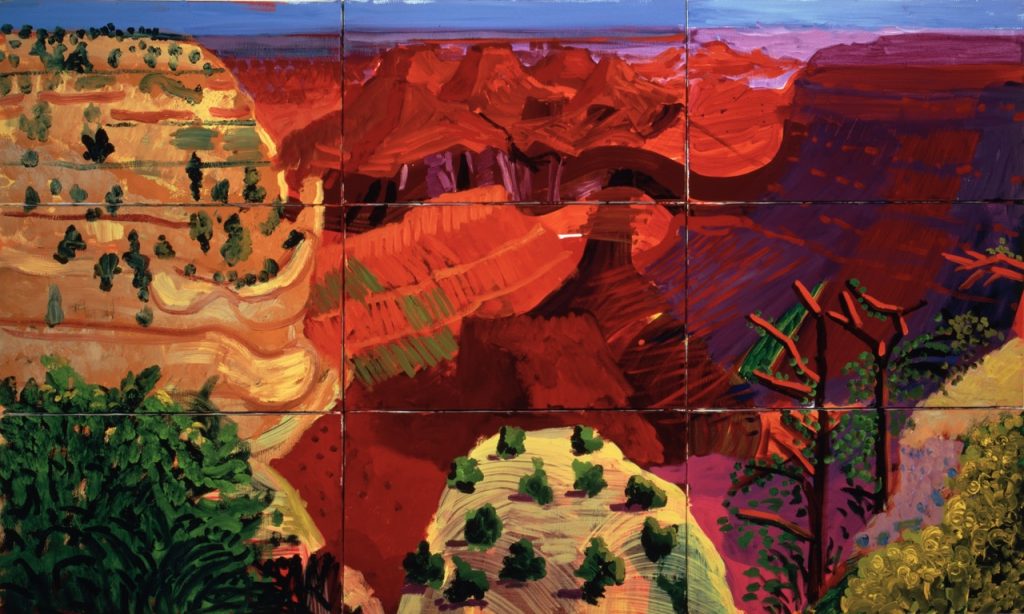

The open landscapes, the clear sunlight, his new friendships, and his bohemian lifestyle kept the artist anchored on the U.S. West Coast for a quarter of a century. He owned homes in Malibu and on the edge of the Grand Canyon. The idea of representing space became increasingly important to him. His immense, vividly colored Grand Canyon works from the late 1990s sometimes span as many as sixty individual canvases.

But more than anything, Hockney sought to remain contemporary. To make use of the techniques of his time. Throughout his life, he went through periods of doubt—wondering if his work was still modern and relevant. Time and again, he experimented with new media—Polaroids, the fax machine, Photoshop, the iPad—only to return, ultimately and with utter confidence, to drawing and painting as the most superior forms of expression.

GENTLE MELANCHOLY

Around the age of 65, Hockney settled with his regular entourage of assistants and friends in the northern British coastal town of Bridlington, not far from where he was born. “People don’t just pass through here,” he explained to art historian and curator Hans Ulrich Obrist. “Here, I have the peace to truly look at things.”

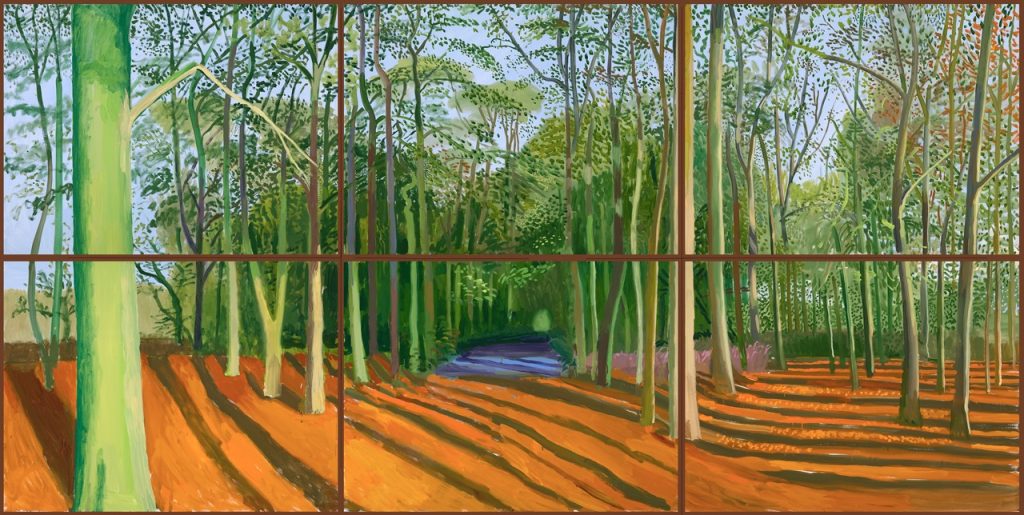

From Bridlington, he focused on depicting the quintessential British landscapes of East Yorkshire—preferably as early as five or six in the morning, when the rising sun cast long shadows across familiar ground. It was the same hilly countryside where Hockney had once worked as a farmhand in his youth, returning home weeks later bronzed and strong after cycling seventy kilometers.

These are breathtaking oil paintings composed of multiple canvases, each one painted based on digital photography. A gentle melancholy seems to have settled over the artist. “The more you know about history, the more you realize how much we love violence and destruction,” he told Obrist. “Deep down, I think we all know we’re going to blow ourselves up.” Powerful words from the man who had always strived to infuse his work with joy.

Hockney has always drawn inspiration from the geography surrounding his studios and from the most ordinary objects around him. Countless sketches bear titles like Ladder and Broom, Hole in the Studio Floor, Ashtray on the Studio Floor, Hat on a Chair.

The people he paints are almost always part of his close circle. Inspired by Van Gogh’s Old Man in Sorrow (On the Threshold of Eternity) from 1890, he began a portrait gallery back in Los Angeles in which he painted a series of acquaintances all seated in the same chair. His brother, his assistant, his manager—he painted them silently, fifteen to eighteen hours at a time, trying to capture them.

“Why don’t you paint famous or wealthy people?” Obrist once asked him. “It’s not a problem I want to deal with,” Hockney replied. “If you don’t know someone well, how can you tell if the portrait resembles them?”

It’s that sense of the everyday, the ordinary, that makes Hockney so popular. You don’t need a degree to understand his work.

“Hockney has an infectious ability to bring new ways of seeing to life,” says assistant curator Helen Little of the Tate exhibition in an email. “His response in a TV interview years ago to the question ‘What makes you so popular?’ kept running through my head while putting this show together. He said: ‘I’m interested in ways of seeing, and in translating those into very simple means. If you can communicate that, then you reach a wide audience.’”

After his young assistant Dominic was killed in a tragic accident in 2013, Hockney sold his house in Bridlington and returned to the United States—the country that had embraced him, reflected him, and lifted him far beyond himself. Wealthy, world-famous, still that boy from Bradford whom everyone cheers for—happiest, above all, under the bright Californian sun.