Haute Couture from the Printer

Advanced techniques in fashion

Iris van Herpen was the first to send a printed dress onto the catwalk. Advanced techniques are increasingly used in fashion. From lasered lace to solar panels in a T-shirt.

Iris van Herpen is the winner of the 2016 Culture Fund Fashion Stipend, which consists of a sum of 50,000 euros. The stipend was established by an anonymous patron at the Prince Bernhard Culture Fund.

Image editor/graphic designer Julie Peeters created a pictorial essay featuring Iris van Herpen’s unique creations for this issue.

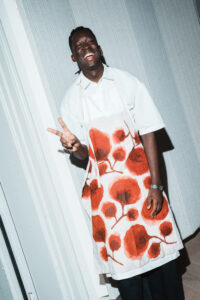

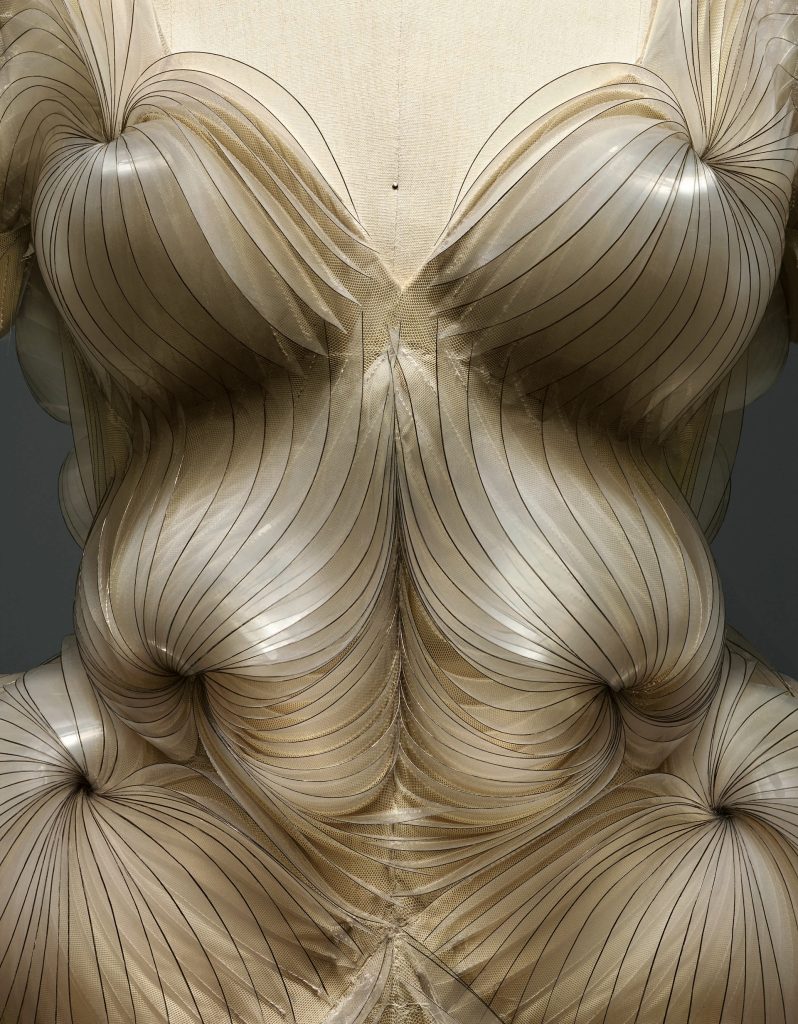

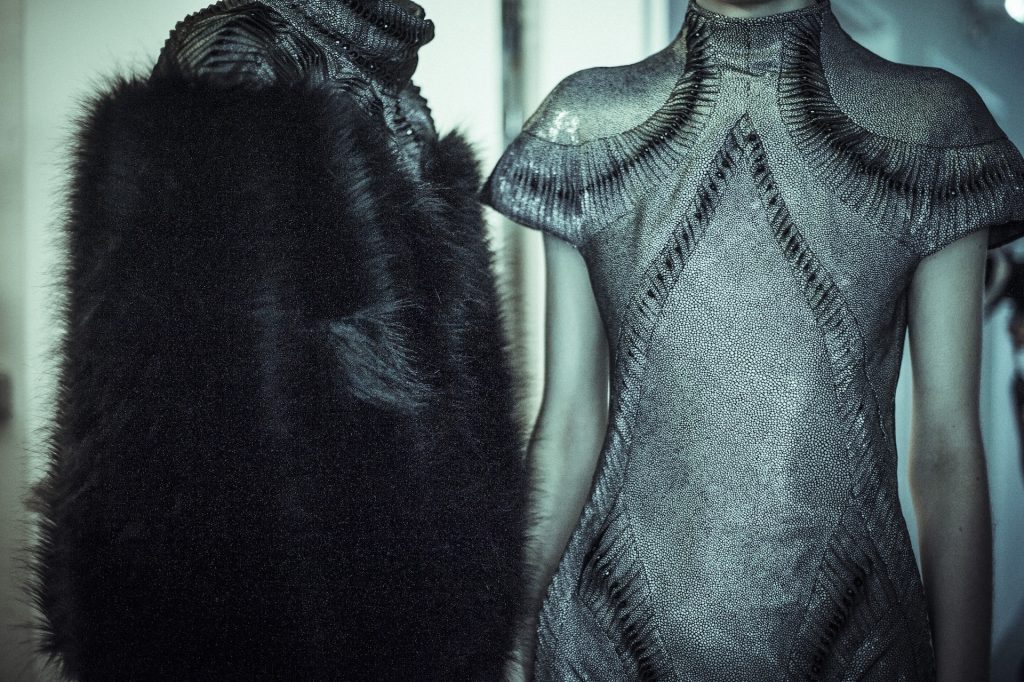

It already exists on the catwalk: a dress whose top layer dissolves when it comes into contact with water. Innovative designer Hussein Chalayan demonstrated this new technique during fashion week in Paris, where the summer 2016 fashion was shown. Two days later, Dutch designer Iris van Herpen presented her new collection. Before and during her show, British actress Gwendoline Christie lay on a platform on the catwalk while futuristic-looking robotic arms produced a woven dress around her on the spot; meanwhile, models walked by in close-fitting garments made of punched and lasered lace.

In 2010, Van Herpen was the first designer to send a 3D-printed dress onto the catwalk. That dress allowed her to join the Chambre Syndicale de la Couture parisienne, the highest fashion body in France, and in 2014 she won the ANDAM Award, a prestigious international fashion prize worth €250,000 and a year of coaching by François-Henri Pinault, the big boss of luxury company Kering. She has since worked with architects such as Julia Körner and Daniel Widrig, and her designs have been worn by Daphne Guinness, Lady Gaga and Björk.

Fashion has been incorporating more technological applications into clothing in recent years, including by other Dutch designers. For instance, Anouk Wipprecht works together with major companies such as Google, Audi and Intel, and last year, during fashion week in Berlin, she presented a number of 3D-printed dresses in which she incorporated LED lights and sensors from the Audi A4. Wipprecht recently became creative director of CODAME Labs, a brand-new research & development studio in San Francisco. There, she works on the development of high-tech fashion, together with various designers from all over the world. One of them is the Dutch Maartje Dijkstra, who combines traditional craft techniques with interactive technologies; her work can now be seen in an exhibition at museum Landgoed Verhildersum in Groningen.

Another Dutch fashion-tech pioneer is Pauline van Dongen, who founded her own studio in 2010 and works on wearable technology. Her best-known project is ‘Wearable Solar’ from 2013, a series of dresses incorporating solar panels that you can use to charge a portable phone, for example. She also made a luminous jacket in collaboration with Philips, this Mesopic / Light Jacket incorporates textile straps with LED lights on them in tunnels of fabric – good for visibility in the dark, but also simply beautiful. And in collaboration with interactive designer Martijn ten Bhömer, she made Vigour for a care institution: a vest that can monitor the wearer’s body movements through electrodes embedded in the yarn.

HAndcraft and The machine

There are currently two major exhibitions in America dedicated to fashion and new technological applications. Tech-style at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston shows how fashion designers and consumers are influenced by technology. And in Manus x Machina: Fashion in an Age of Technology at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the role of handwork (manus) and machine work (machina) in fashion is explored.

According to Andrew Bolton, curator of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, handwork is wrongly seen as superior to machine work. According to him, most fashion designers do not make such a clear distinction at all. For them, to arrive at creative solutions, traditional craft techniques are as valuable as technological developments. Bolton is just saying: the traditional dichotomy between haute couture as synonymous with exclusive handwork and prêt-à-porter as synonymous with cheap machine work is outdated. One of the examples Bolton cites to underline his theory is a Chanel wedding dress from the winter 2014-2015 collection. The pattern on the train of that dress was drawn by hand, worked on with a computer, printed with a machine and, finally, pearls and gemstones were put on by hand; in total, it involved over 450 hours of work.

Among the over 100 designs on show at The Metropolitan is the aforementioned dress by Chanel, as well as futuristic 3D-printed dresses by Van Herpen and antique couture pieces by Charles Frederick Worth (1825-1895), the founding father of haute couture, who was the first to sew his brand name into garments. But there is also work by other contemporary designers using rare craft techniques and cutting-edge technological production methods. Think of the designs by Lazaro Hernandez and Jack McCollough of popular New York fashion brand Proenza Schouler: for one of the dresses in the summer 2016 collection, they went to work with machine-knitted viscose combined with white and red feathers that were put on by hand.

Where does the new tech fashion trend come from? The most obvious answer is the state of current technological developments. More and more is possible. The forerunners are applying the new techniques to differentiate themselves and optimise the production process. Think of Van Herpen, which has found a clear niche with its futuristic fashion. Or the graduation collection of Karin Vlug, who won the 2014 Frans Molenaar Couture Prize: in her search for a new way to assemble clothes, she researched the fusibility of synthetic materials and fused together several layers of fabric into garments.

In this sense, contemporary designers are not so different from their predecessors. The rise of haute couture in the 19th century paralleled that of the sewing machine, introduced by Barthélemy Thimonnier in 1829 and improved by Elias Howe in 1846. The already-mentioned couturier Worth used the perfected version of the machine introduced by Isaac Singer in 1851. So new technologies have always been an important tool in fashion. Fashion brands tempt consumers to buy as much as they can despite the crisis. There is nothing sustainable about that – consumers are starting to realise that has been.

But it is too easy to attribute the current boom only to the availability of such advanced technologies. The penchant for tech fashion is also a counter-reaction, related to a changing perception of fashion in response to a number of social developments. ‘The fear around technology has become less and less in the last decade,’ says Anneke Smelik, professor at Radboud University, who writes in the book I, cyborg. Man-machine in popular culture writes about the changing attitude towards technology. ‘Many people sleep with their mobiles in bed, for example. And most mobiles and iPads you have to stroke to operate them. I think that stroking is almost a material expression of the way we have come to look at technology. We are now to the point where a larger group of people are slowly becoming receptive to wearable tech.’

Ecological and financial crises are also affecting the application of technology in fashion. The consequence of the ecological crisis is a scarcity of raw materials such as cotton, which more or less forces designers to do more material research. Due to the financial crisis, many consumers have less to spend and fashion brands are under pressure.

'Many people sleep with their mobiles in bed. And most mobiles and iPads you have to stroke to operate them. I think that stroking is almost a material expression of the way we have come to look at technology. We are now to the point where a bigger group of people is slowly becoming receptive to wearable tech.'

Always something new

The pressure is currently so high that collections are succeeding each other faster and faster: fashion brands are pulling out all the stops to entice consumers to buy as much as possible despite the crisis. Many brands – both expensive and cheap – have adopted the model of fast-fashion chains such as H&M and Zara: new items hang on the shelves every week. There is nothing sustainable about that, and more and more consumers are starting to realise this.

Trend guru Lidewij Edelkoort even goes so far as to declare the current fashion system dead. She did so last year in her ‘anti fashion’ manifesto, a lecture with which she caused quite a stir. According to Edelkoort, who en passant predicts a revival of couture, fashion should again be about the garment itself, about fabric and cut, instead of marketing and show.

With her manifesto, the trendwatcher articulates a sentiment that is more widely felt. The leading fashion blog businessoffashion.com also regularly writes about how the fashion world could operate more sustainably. For example, Marie-Claire Daveu, ‘chief sustainability officer’ of luxury group Kering, wrote that every fashion brand should embrace sustainability as a guiding and central value rather than just using it as a marketing tool. And in contrast to the brands that produce ever faster and ever more, there is now a growing group of designers who consciously focus on making innovative products that enable them to contribute to a sustainable fashion industry.

Because it is precisely in the field of sustainability that new technologies can be of great significance. Imagine that it will soon be possible for everyone to have flexible material come out of the 3D printer. Then the entire fast-fashion industry might be overtaken by the possibility of downloading digital files for clothes, shoes and jewellery and then printing those designs themselves at home.

In the field of material use, too, new technologies allow great leaps forward towards a more sustainable fashion industry. Consider fibre recycling: textiles and other materials can be decomposed down to the fibre, thanks to current technology, so that the raw material can be reused.

This has led, for example, to the designs launched by fashion brand G-Star in collaboration with pop artist Pharrell Williams. Under the name ‘RAW for the Oceans’, they are creating a denim collection that incorporates stray plastic from the ocean.

Another clever technology: laser technology, which is increasingly used these days. Logical, as laser cutting is more efficient than cutting and therefore leads to less waste. Laser technology is also widely used for decorations; for example, Van Herpen’s 2016 summer collection includes a number of dresses made of lasered lace.

Yet the most advanced techniques – such as 3D printing and integrating solar panels – still make it to the catwalk only sparsely, let alone the shop floor. This is due to the speed of the current fashion system. Many projects that focus on the application of new techniques remain stuck at the prototype stage. This is because it takes a long time to develop them into clothes that can actually be worn and are affordable for a large group of people.

And so, for the time being, many of these designs carry couture price tags: the first ‘Wearable Solar’ designs were bought by museums and so were a number of Van Herpen’s garments; they can be seen in museums or worn by a limited number of people. Integrating new techniques takes time. A lot of time, and there is hardly any in the fashion world at the moment because trends follow each other at an enormous pace.

The new tech fashion may not be handmade, but it is just as labour-intensive and exclusive, and just as expensive: in fact, it is the new haute couture.