5x Hosting Like an Artist

From Judy Chicago to Salvador Dalí

A great host is a universe: a connector who brings people together and holds space for something to be born that wasn’t there before – for moments that may one day enter history, like the legendary dinner parties of Judy Chicago, Cleopatra, Salvador Dalí, Henri Rousseau and Gertrude Stein.

1. JUDY CHICAGO

Artists have long used dining together as a narrative tool: the shared meal in Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper symbolises fellowship and betrayal; leisure and friendship gather round the table in Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s Luncheon of the Boating Party; and Edward Hopper’s Nighthawks uses the near-empty restaurant – eating alone – to convey isolation and loneliness. But few artists have used the layered symbolism of the dinner table, consumption, and historical representation more powerfully than Judy Chicago with her seminal work The Dinner Party, created to address the erasure that eclipsed the achievements of women.

First exhibited at SFMOMA in March 1979, The Dinner Party elevates female achievement in Western history to a heroic scale traditionally reserved for men. The installation is a massive ceremonial banquet laid on a triangular table measuring 48 feet (about 15 metres) on each side. Chicago represents thirty-nine notable women – goddesses like Ishtar; ancient queens and pharaohs like Hatshepsut and Eleanor of Aquitaine; and modern icons like Virginia Woolf, Georgia O’Keeffe, and Sojourner Truth. Each woman is honoured with an elaborately designed place setting, often featuring raised central motifs based on vulvar or butterfly forms – which Chicago framed as ‘central core’ imagery.

2. CLEOPATRA

Cleopatra was the queen of dinner-party diplomacy. A woman who knew how to make an entrance, she would arrive at her parties on a gilded barge, reclining beneath a gold-spangled canopy, perfumed purple sails leaving her scent on the breeze. That’s how she arrived at the Tarsus reception in 41 BCE, an elaborate occasion that won her the political support of Mark Antony. Together they revelled in public pageantry, hosting events like the ‘Inimitable Livers’ – a society devoted to feasting in inimitable style.

As pharaoh, Cleopatra understood the earthly concepts of power and control, but as goddess and divine intermediary it was her task to maintain cosmic order, and she did this by performing rituals and making offerings to the gods and ancestors. Ancestral feasts – serving the favourite foods of loved ones who have passed – are an ancient practice across the world. These spiritual dinner parties are used as tools for healing, connecting and maintaining intergenerational bonds, making them perhaps the most impactful type of dinner party there is.

3. SALVADOR DALÍ

Salvador Dalí – artist, author, critic, impresario, provocateur – knew how to take a seat, usually at the head of his own table. Perhaps his most elaborate was ‘A Surrealistic Night in an Enchanted Forest’, a 1941 charity ball at the Hotel Del Monte in Monterey, California, to aid refugee artists during the Second World War. Dalí’s shopping list read like theatre: 2,000 trees; 4,000 hessian bags; newspapers; animal heads; headless mannequins; high heels; the largest bed available in Hollywood; as many gourds as possible; a wrecked car; a sedated nude woman and live animals from the San Francisco Zoo. Dalí’s wife, Gala, wore a unicorn head and fed a lion cub from a Coca-Cola bottle with a giant nipple. Guests ate avocado and crab served out of stilettos, and live bullfrogs sprang off silver platters when the lids were removed. The dinner party was a spectacle and brought a lot of attention to Dalí, but it cost so much to produce that he didn’t raise any money – a fundraising failure.

4. HENRI ROUSSEAU

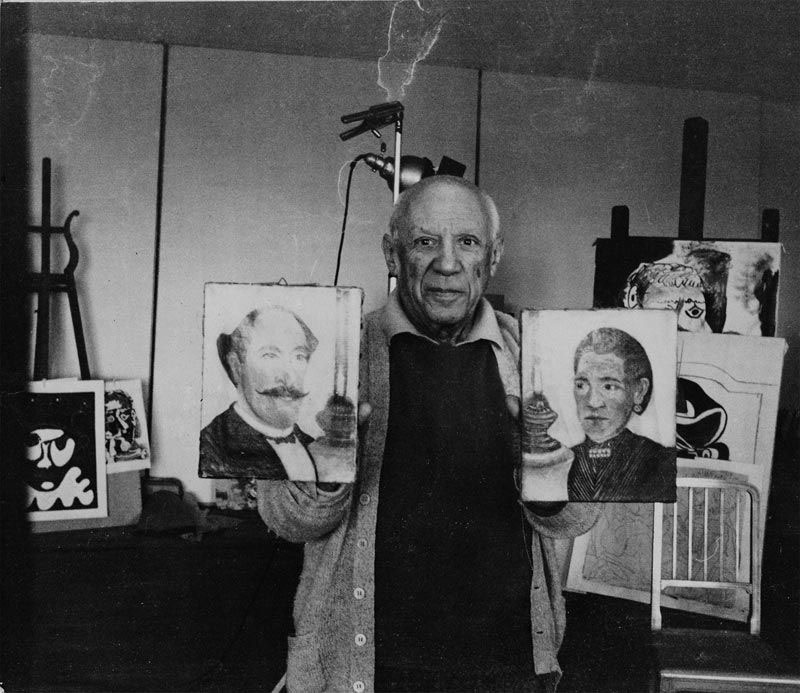

It was 1908, and Picasso had just bought a cheap painting by Henri Rousseau. Then sixty-four and widely denigrated, Rousseau became the pretext for a joke: Picasso and Guillaume Apollinaire planned an over-the-top dinner party for him. They invited Gertrude and Leo Stein and Marie Laurencin. A guest list that raucous doesn’t assemble for a nobody; the night proved Rousseau mattered. The party teemed with mishaps: catering didn’t show, forcing Gertrude Stein to wander the streets for sardines and camembert. Rousseau arrived, violin in one hand, cane in the other, serenaded by pumping accordions and a poetic toast ending with ‘Long Live Rousseau!’ Within hours, gate crashers arrived. Someone brought a donkey; Marie Laurencin did a striptease and fell into a mountain of desserts. Poets punched each other, and Rousseau, delighted, told Picasso, ‘You and I are the greatest painters!’ Everyone heard it, and believed. Rousseau left with the Steins, the rest slept on the floor.

With Picasso’s endorsement of Rousseau, public perception shifted and he was from that moment treated as a major talent. This makes me wonder how arbitrary ‘talent’ is, and how far it rests on being at the right time, right place and at the right dinner table.

5. GERTRUDE STEIN & ALICE B. TOKLAS

A great host is a universe: a connector who brings people together and holds space for something to be born that wasn’t there before. No couple did this better than Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas. At 27 Rue de Fleurus, a few steps from the Luxembourg Gardens, their apartment was the central nervous system of art and culture in Paris. Toklas would design the menu and have the cook prepare the food for the guests, sometimes with a custom menu for a particular guest. She designed ‘Fish for Picasso’: cold sea bass decorated with stripes of red mayonnaise, sieved eggs, truffles, and herbs, or served her classic show piece, poulet demi-deuil – a dinner party centrepiece that looks like a chicken wearing the veil of a woman in mourning.

Painters and writers like Picasso, Matisse, Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and Thornton Wilder dropped in regularly. But there were also regular folks and travellers who would stop by – curious and engaged in the culture of the time. Front-facing, Stein entertained the artists, while Toklas designed the menu, tended to the wives, and made these weekly parties happen.