Steve McQueen: ‘There is cinema before and after Robby Müller’

Interview Steve McQueen

Dutch cameraman Robby Müller, who was honoured at Eye Filmmuseum in 2016, is the muse of a number of great filmmakers. Dana Linssen spoke to director Steve McQueen about Müller: ‘a man who chases clouds and writes poems with light.’

There is cinema before and after Robby Müller, says Netherlands-based Steve McQueen (London, 1969), director of award-winning films as Hunger (2008), Shame (2011) and 12 Years a Slave, which was awarded three Oscars in 2013. We sit in an old-fashioned Amsterdam lunchroom and talk about Robby Müller, friend and cameraman, who will be honoured with a retrospective at the EYE Filmmuseum in Amsterdam this summer.

There is no film lover who has not seen one of Müller’s films at some point. You only have to close your eyes or the images loom up: Nastassja Kinski’s red jumper in Wim Wenders’ Paris, Texas (1984), the thousands of colours of black and white in Jim Jarmusch’s Down by Law (1986) and the dancing digital cameras in Lars von Trier’s Dancer in the Dark (2000). The memory alone brings you back to the here and now of the there and then of those films. What exactly were they about? No idea. Why that man was walking through the desert in Paris, Texas? What those three escaped convicts in Down by Law were up to? Why you had to cry so much at the tragic fate of singer Björk in Dancer in the Dark? The stories were forgotten, but the images remained. A shot of a man walking for so long that you yourself get blisters on your feet and sand between your lashes squeezed shut against the blinding sun. Three men in a black and white swamp who themselves became strange growths taking root in the wetland. Björk’s face, ever elusive, as if she were the one dancing and not the dozens of cameras around her.

That’s what those films were about.

How time moved.

We talk to Steve McQueen, who has just returned from Chicago, where he is working on a new film with writer Gillian Flyn (Gone Girl). By that ‘before and after Robby Müller’, he means this: ‘Just look at the films Wenders, Jarmusch and Von Trier made before, after and with Robby. Robby is like Mick Taylor, who played with the Rolling Stones in the 1970s. Brian Jones had just died, and everyone thought the Stones would be finished. And then came Mick Taylor, with whom they made their best albums.’

You could call the 1940 Willemstad-born Müller the muse of great filmmakers like Wim Wenders (with whom he made some 20 films), Jim Jarmusch and Lars von Trier. A muse behind the camera. Who encourages directors to let go of fixed ideas about film and thus inspires them to the beauty of transience and casualness. A painter with light, he has been called. His shots have been compared to the street photography of Walker Evans, the paintings of Hopper, Breitner and Vermeer. He received the Bert Haanstra Oeuvre Prize from the Dutch Film Fund in 2009 and an award from The American Society of Cinematographers three years later. What was praised was his versatility – and his modesty. All this may also say that there is no such thing as a typical Robby Müller film. That it is perhaps more about how he looks, and how he lets you see and experience that as a spectator in the cinema, more than about what exactly comes in front of the lens.

Yet atmosphere is not the first thing that appeals to him in a script, he told me when I interviewed him in 2007 on the occasion of the exhibition Someone Makes a Call and the Sun Goes Down in Den Bosch, when his ten favourite film clips were shown simultaneously in an exhibition space. It was the beginning of Müller’s rediscovery in the Netherlands. He must also have a click with the story. Filmmaking for him is reacting, he said at the time. You can react to a story. Then the atmosphere follows naturally. That is also why he prefers to film actors rather than empty spaces, he said when I presented him with the choice between people and locations. Philosophically: ‘The light has to be able to fall on something. With light, you pass space.’

McQueen and Müller have been friends for 20 years. McQueen: ‘I was just in the Netherlands and wanted to meet him.’ It was shortly before he would win the prestigious Turner Prize. At the time, McQueen was best known as a video artist, had studied film in New York after art school in London, and the thought of a feature film had been playing through his mind for some time. Müller had just shot Breaking the Waves for Lars von Trier and was making school with his moving camera. McQueen: ‘I just called him bluntly. At first I couldn’t find the address, so I called him again and then we agreed to meet at Café Wenders, which of course is a nice coincidence. I was nervous and excited, rattling on and on about all my ideas and plans. I really wanted to work with him, but I didn’t yet know exactly what. I saw him as someone who makes poems with light.’

He describes how their conversations since then: ‘With Robby, it’s all about listening. Even though he doesn’t say much himself. So you have to listen very carefully. And someone like me, in order to fill the silence, starts talking through that enormously. But he just sits there, with his cigarette, his coffee, and every now and then he says something amazing.’ When his wife later asked him how that first appointment had gone, he said: ‘I have no idea what the guy was all about, but I do want to work with him.’

‘I have no idea what the guy was all about, but I do want to work with him.’

The call of light

There is a paradox in Robby Müller’s work. More than once, he has said he is not interested in beauty. ‘He doesn’t care about style, that’s his gift,’ Wim Wenders once described it. Müller himself said: ‘It is easy to make a beautiful image. It is much more difficult to make an image that does not look composed.’ And: ‘Don’t make it more beautiful than necessary. Beauty destroys drama.’ But meanwhile, his images are always of a comforting beauty. There may be drama, but at least there is redemption.

Müller developed his searching, observational style, written in natural light, more or less by necessity. In an interview with the US trade magazine American Cinematographer, he once said that in the 1960s, when he had just come from the Film Academy in Amsterdam, the film industry in the Netherlands was so under-developed that, as a cameraman, you had almost no opportunities to play with light. Because you couldn’t make the light, you had to wait for it, or after it. He learned not only to look at the light, but also to listen to it. He followed the call of light.

McQueen: ‘He functions best when he doesn’t have to work with big crews, not too much paraphernalia, no restrictions from the American unions, which don’t allow Europeans on set. In the early years he worked in America, all that was not so tightly regulated. After that, it became harder for him to keep his individuality in it. Robby taught himself to improvise at the beginning of his career; at the same time, you might also think that he was always like that, he thrives in circumstances where he can follow his feelings, his intuition, without too many restrictions. Later, he once told me that filmmakers often came to him with a great well-defined plan, but then there was, he described it, no more room for him.’

Weightless

The work Steve McQueen and Robby Müller made together is full of space. Having found the right project to work on together, they moved to the Caribbean island of Grenada, where McQueen’s parents are originally from. The film shot there for the video installation Carib’s Leap (2002) takes its title from a rock point where the last resistance fighters against the European colonisers chose death in 1651. Small images of mundanity are intersected with the image of a man floating in the air, somewhere between leaping and landing. Never do we see him drop off, never come down. Just before death, everything is weightless.

Ten years later, McQueen discovered a forgotten piece of film that Müller had shot with him there, but which had not made it into Carib’s Leap: dreamy shots of a beautiful, proud boy on a boat. Back in Grenada, he asked where he could find this boy, Ashes. Turned out he was deceased. The film material still found a way into the installation Ashes (shown at the Venice Biennale in 2015).

‘When I think about that film now, I realise that what happens in front of the camera is just as important as what happens behind the camera. It was an unexpected, unplanned momentum of two people who were in their optimum. Ashes full of life force, and which is now no longer there. Robby who had the intuition to put him on that boat and out to sea, and who is now no longer who he was.’ There is a short silence. ‘Surely that’s very strange.’

For McQueen, Müller is a kindred soul. ‘I think for me the process of filmmaking is as important as it is for him. It’s about freedom. Possibilities. There are so many cameramen where the frame seems to be fixed in advance. With Robby, I never think about frame, but about flow. That’s why you really shouldn’t watch stills of his films, because they are not made to stand still.’

‘I see Robby as a musician, a jazz guitarist. He listens to what you have to say and interprets it. He fills it in, improves it. Robby is a musician with a camera. He feels things. He is like a tai chi cameraman: he knows where the energy is, and he follows it. There is a fantastic anecdote from the time of Paris, Texas, that he saw a sky he wanted and jumped in a car with Wim Wenders to chase the clouds. You can only do that if you can let go of control. Did you know that butterflies are Robby’s greatest passion? As a cameraman, he is always butterfly hunting. What is going on? What is happening? It’s about the thrill of being in the moment.’

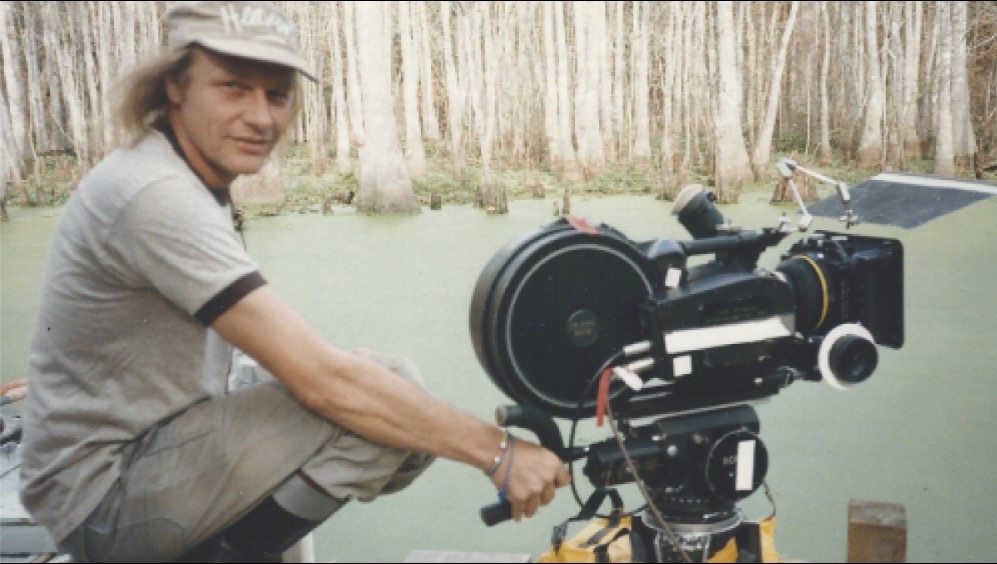

Robby Müller on the set of Jim Jarmusch’s Down by Law (1986). They met at the 1980 Rotterdam Film Festival during a boat trip for festival guests through the harbour. The anecdote about their meeting is classic: Jarmusch asked Wenders where he could find Müller, Wenders said: at the bar, next to the peanut machine. Jarmusch: ‘And there he was, at the bar, next to the peanut machine.’ It characterises the dry humour of the films they would make together.