Gardens of Eden

Noma

Chef of the world’s best restaurant, René Redzepi, found his equal in Piet Oudolf. Both being radical pioneers in their exploration of the natural world, Noma’s kitchen and Oudolf’s garden are closely intertwined. ‘His mission has been to rediscover ingredients most of us didn’t know were edible.

‘Beautiful winter landscape – again it’s amazing that the garden works in all seasons,’ reads one of René Redzepi’s notes, scribbled on a post-it stuck between the pages of the book Oudolf Hummelo. Another, a few pages earlier, beside a photo of a summery Oudolf landscape full of waving grasses and a boisterous expanse of purple flowers, reads: ‘Incredible. Would be amazing for Noma landscape (with edibles).’

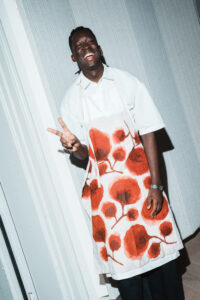

The book sits in a large wooden bookcase at Noma – between shelves housing dozens of awards and Michelin star certificates – in a long corridor linking the restaurant’s kitchen to its ‘back office’. Pantries and fridges, the canteen (where two trainee chefs produce meals every day for the 85-strong staff), the head sommelier’s office and the fermentation lab. Parallel to the corridor is the long path traversing the Piet Oudolf garden adjacent to the restaurant. This is where, for the restaurant’s guests, the Noma adventure begins. ‘Losing everything you have from the outside and coming into a new world… The walk down this path to the restaurant gives you exactly that, it’s sort of a ritual,’ says Liv Linea Holm, who is showing me around the garden where she spends her days. Once a volunteer and summer help, she has been head gardener since 2020 and knows the ground beneath our feet like no other: ‘I spent the first three weeks of my summer job weeding and mulching,’ she laughs. ‘I didn’t know Piet before I started working here; I have a background in biology and I’m still doing my master’s in agriculture. It has been super interesting to get to know Piet’s work and to discover the restaurant world, which was totally new to me.’

The calm of the garden remains outside as you set foot in the building. The sounds from the speakers reverb through the kitchen as preparations are being made for the 16-course menu of the evening. Some of the staff have already gone to Kyoto, where they are doing a pop-up in the spring. Something they have been doing in recent years, in Australia and Mexico, in order to soak up impressions of foreign places and cultures, and to bring them back to their own kitchen in Copenhagen.

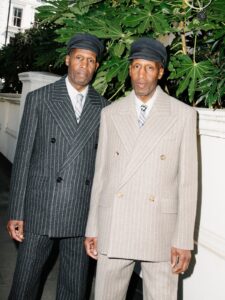

Danish chef René Redzepi opened Noma twenty years ago. He is now one of the most influential chefs today, with a three-star restaurant, that was awarded the title best in the world five times. In 2018, Redzepi moved his team to the current location, a former ammunition bunker on the edge of the city, with enough land around it to create a garden. Redzepi had seen Oudolf’s work at the World Exhibition and knew he had to have him at Noma.

The most important condition was that the new garden had to be interesting all year round – after all, people come from all over the world to visit the restaurant, even in the winter, which can be long, bleak and barren. And who other than Oudolf, would be able to achieve that? Oudolf: ‘The aim was to maximize colour and bloom for as long as the climate permits. Allowing a plant to grow and flower, to die and decay in full view, invites us to discover the beauty of structure, the sculptural intricacy of a seed head, the way a plant’s skeleton appears etched against the sky.’

Discovering beauty in the unexpected and living in harmony with the seasons are part of Noma’s philosophy too. Like Oudolf, Redzepi was a pioneer in his limitless exploration of the natural world. Wild and local ingredients are at the heart of his cuisine. Experimentation with unorthodox techniques and methods of preparation became his trademark. ‘René’s mission has been to rediscover and elevate ingredients most of us didn’t know were edible,’ says Oudolf. And in that way the chef was as radical as the landscape designer. ‘Much of my work has been with plants that until not long ago were considered unworthy of gardens. Grasses became a way for me to create more spontaneity than I saw in the stiff, decorative gardens of the past, with their clipped boxwood hedges. Grasses have more staying power and start flowering late. They bring sensual movement to a landscape. More importantly, they remind you of the wild and where we come from. They evoke the prairie and other untouched landscapes.’

Redzepi and Oudolf created a plan for a garden divided into three sections, each with its own identity: first, the oneiric perennial garden; then the ever-changing experimental garden, featuring edible plants; and finally the shaded fern garden at the rear.

The garden and restaurant are a single entity, with the changing seasons determining the aesthetics and the menu. ‘There’s a strong collaboration between the garden and the kitchen,’ Holm says. ‘Especially in the summer, when it’s all plant-based. We use Piet’s garden for the bouquets on the tables and the decorations of the dishes. We use flowers and leaves that are hard to get a hold of. Some things we pick three hours before service. And with the kitchen, we have to plan all this out and adjust to changes like the weather.’ Because when you’re dependent on the garden, you sometimes need a back-up plan. Redzepi: ‘A week of rain might nix your cherished asperagus dish.’

At the same time, both garden and kitchen have their own rhythm and routine. ‘After the garden was planted, Piet had a talk with the staff and he spoke about how in the kitchen you get to change things and make adjustments all the time, but in a garden, you have only one shot, one chance to plant or change things, and then you have to wait and see how it evolves. So it’s a different rhythm; in the restaurant you also work with the seasons, but in the garden you need to have a more long-term vision. That’s interesting about working with the restaurant as a gardener, we learn a lot from each other’s way of thinking and working.’

The fast pace of the kitchen allows greater experimentation and endless modification. Holm: ‘That’s typical Noma: trying out crazy things and seeing what happens.’ That evening, I witness this first hand when, at some point during the sixteen incredible courses of the ‘Game & Forest’ menu, a fluorescent yellow drink was poured. When I ask about the origin of the brew, a member of front of house comes back with a large glass jug containing what looks like a piece of pale orange rubber, preserved in formaldehyde. It turns out to be scoby: a culture of yeasts and bacteria that is used to make a fermented tea drink called kombucha. Like this, the scoby looks rather tough and unattractive, but Redzepi thought: why don’t we try eating it? A bit later, paper thin triangular slices of ‘kombucha mother’ – now looking rather like sashimi – appear on a plate, accompanied by rosehip berries, apple and a quince broth. The remainder of the menu features the glorious pumpkin with white currant leather and a sauce of fermented barley and jasmine, a typical Danish æbleskive, with herbs and crispy bear fat, and the final small but showstopping dish: a chocolate and reindeer caramel presented in the form of a lit candle, edible in its entirety once it is extinguished.

‘Creativity, for some strange reason… It’s having complete order and at the same time complete chaos and freedom,’ says Redzepi. The kitchen is a controlled sanctuary, as is the garden: ‘Piet is very good at finding that balance, making it look wild but not messy,’ says Holm. ‘We have a continuous conversation about the garden. Piet gives me a lot of advice, but sometimes the plants behave differently here than what he’s used to in other places. The garden is very much allowed to evolve as it wants, but we also have to make decisions about what to do when certain plants seed for example, or when some plants become more aggressive and take over.’

My evening at Noma is almost over when someone tells me to hang on for a final guided tour. Even as the last guests linger at their table, aluminium pans glint in the kitchens as if nothing has happened, and transparent containers of forest broth are being stored away in the cool room. It is not hard to see why this relentless rhythm and incomparable quality have an expiry date. Early this year, Redzepi announced the restaurant as we know it will be closing at the end of 2024. It is time for Noma 3.0, conceived as a kind of vast laboratory or ‘factory of nature’: a test kitchen devoted to food innovation and the development of new flavours. ‘Serving food to guests will still be part of what we do, but being a restaurant will no longer define us,’ says Redzepi. ‘We have to completely rethink the industry. This is simply too hard, and we have to work in a different way.’

The garden will continue to exist, also in relation to Noma, although – as Holm explains – its function will change somewhat, since it will primarily serve to supply the test kitchen, and research and product development, rather than a day-to-day menu. ‘We’ll see what happens. For me, it has always been such an honour and a privilege to work in a garden like this. Everywhere, resources are precious, and to be allowed to work on something beautiful is very fulfilling. But most of all… I just like the daily act of working in the garden. So I’m glad that we can go on working in the garden like we’re used to, at least for a while. For me, the most important thing is that the garden will continue to be taken care of, and I hope that far more people will be able to visit it in the future.’

Meanwhile, the culinary world anxiously waits to see what form Noma will take when it returns to the scene – does this mean the end of ‘fine dining’, of 20-course menus, and what will replace it? But before something new can emerge, space must be created. ‘To continue being Noma, we must change’, says Redzepi. He wants to create a place of unconstrained learning. A playing field in which taking risks is encouraged.

Back in the long corridor with the bookcase, beside the framed sketches of Oudolf’s garden, my eye falls on a drawing by David Shrigley, one of Redzepi’s favourite artists. Every departing member of staff receives a print to take home. The work, featuring Shrigley’s handwritten red letters, expresses both a hope and a promise: ‘Knock everything down. Build new stuff. I will help (with both)