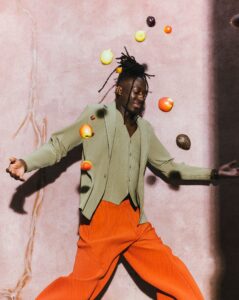

‘I have always been good at adapting.’

Interview Iwan Baan

A suitcase and a child-buggy are perhaps the perfect symbols of his working life. The Dutch-born photographer Iwan Baan (b. 1975) has spent the last fifteen years travelling all over the world to capture the places we call our own. National borders were mere lines in the sand; every city was a stop on the way to somewhere else.

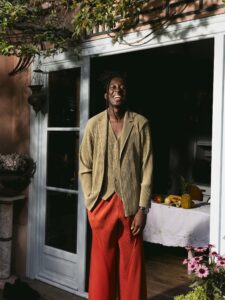

Sitting across from Iwan Baan in his corner house in Amsterdam’s historic Jordaan district, I feel like a birdwatcher with some rare migrant species in his sights, just alighted and about to take flight again. In the background, chugging away like an electric coffeemaker, a computer loads Iwan’s latest set of photos. Beside us, next to the front door, stands a baby buggy, together with two camera bags and an in- destructible-looking steel suitcase. In the last 30 days, Iwan has made 21 flights, often doing his postproduction on the plane to save time. His commissions all come to him by e-mail.

A suitcase and a child’s buggy – perhaps the perfect symbols of Iwan Baan’s working life. The Dutch- born photographer (who grew up surrounded by Dudok-designed buildings) has spent the last fifteen years travelling all over the world photographing the work of leading architects. National borders were mere lines in the sand; every city was a stop on the way to somewhere else. When a strange accident led to his Amsterdam home burning out in 2011, it was actually a relief: it meant he had no excuse to stop travelling. And his immediate family – his Canadian wife Jessica and two kids (aged two and six) – invariably travel- led with him, assisted by an au pair. The usual pattern was two months in the United States followed by two months in the Netherlands – they had a special agreement with the schools in both countries to be able to take them in and out and move back and forth, he calls it the ‘nomad exemption’. The children are being brought up bilingually.

When he arrives in a place, local people frequent- ly don’t realize he’s a photographer. He built his own camera at the age of sixteen but these days, with his handy 35mm digital camera, Iwan looks more like a tourist than a professional photographer. No assistants, no tripod. But he does frequently hire in helicopters or, where it’s impossible to hire aircraft, use a small drone to get his renowned aerial shots.

And then came 2020: the year of the great caesura, when the skies suddenly emptied and globetrotters like him found themselves confined to home. ‘Actually, you could feel it coming right from January’, Iwan recalls. ‘Jobs were postponed, then put off again. New commissions came with no dates attached. People were nervous, you could hear it in their voices. And in February the world started to go into lock-down, our freedom of movement was gradually reduced.’ He gives me a cup of coffee, spat out by the Nespresso machine in the kitchen. His voice is soft and friendly, the sort used in wildlife films. He wears a shirt and sweater. As always, he is unshaven, his short black beard stippled with grey. We are in his office on the ground floor of the house. Black tables pushed together, Apple monitors, and shelves holding Iwan’s latest books. The family lives upstairs, in what used to be its pied- à-terre. Prior to the lock-down. ‘In March, the dominoes began to topple. I was in Sweden. I got on the last flight to Amsterdam before the whole country closed down.’

Once back in the Netherlands, the family faced a difficult decision. ‘Should we go to America, where we’ve got another house, in upstate New York? We have got lots of space there, surrounded by woodland. But, against that, here we’ve got a support network of friends and relatives. We were a bit chary of rural America. We thought, if things go pear-shaped over there, everything will shut down. And we were right: two weeks after we decided to stay in the Netherlands, the only local hospital near our home in America clo- sed its doors.’ The au pair returned to the US but the family remained at base in Amsterdam.

Wasn’t it depressing, suddenly having his wings clipped like that? He smiles. ‘I’ve always been good at adapting. Circumstances change, people adjust.’ If you had to identify any one leitmotif in his work, that would be it. For perhaps the first time in his career, he was forced to travel in a different way; not so much from place to place as backwards in time, through his past work, creating a paper trail that would end in this edition of See All This. A journey to places that give Iwan hope. What does he mean by hope? I’ll come back to that later.

But first the question of how an architectural photographer could turn himself into a travel guide. Because the term ‘architectural photographer’ has never quite covered what he does. What Baan documents is not so much architectural edifices as the people who move around within them, stand next to them or live in their vicinity. People adjusting to change. The face of the building is visually attractive, but not so much as that of the old man gazing at it. The viaduct is striking, but not as striking as the tent city that has sprung up below it. Somewhere, in a French-language description of his work, I read that ‘Sous la pierre d’Iwan Baan, il y a toujours un coeur qui bat’: beneath the stones he photographs, there is always a beating heart.

And that’s a refreshing change. For decades, architectural photography has been all about producing coldly aesthetic images that present buildings not as the setting for people and their lives, but as perfect and inviolable monoliths that stand in the landscape awai- ting admiration and reverence. That was how Baan’s predecessors, legendary photographers like Julius Shulman and Ezra Stoller, approached their subject. But perfection has never really interested Baan. By his own admission, he doesn’t ‘know anything about ar- chitecture.’ The real world is messy, he’s sure of that; cities are messy; people are messy. And given that buildings are not monoliths but an integral part of their environment (which they also help to shape), they should be depicted as messy.

Footsteps on the stairs. Jessica comes into the room. The office printer also serves the household; she fiddles with it, then goes back upstairs. Somewhere in the distance the slurred gibberish of a man stum- bling through the narrow, centuries-old streets of the Jordaan. Iwan smiles.

Perhaps his iconoclastic attitude is due to his atypical background. He studied for a while – photography at the Royal Academy of Art in The Hague – but never completed his degree. He’d gone to do a placement in New York and the department agreed to a digital presentation of his final year project, then changed its mind at the last minute. The staff, all traditionalists in love with analogue, felt that photographs should be printed; viewing them on a monitor or projected on a screen was beneath their dignity. His submission was turned down. Stuff it, thought Iwan, who was just launching his career. In retrospect, it was the perfect moment: digital photography was taking off, its quality was improving with every new model, and globalization was rampant. History was on his side.

Since then, he has worked with illustrious architects like Rem Koolhaas (with whom he began to work when CCTV Tower, headquarters of the Chinese state television service, was under construction: a process he followed closely). Other big names followed: Herzog & de Meuron, SANAA, Frank Gehry, Toyo Ito, Steven Holl, Zaha Hadid, Sou Fujimoto and Selgas Cano. ‘It all happened quite naturally. I was travelling a lot, bumping into these architects and hearing about their fascinating new projects. It was a unique moment in time: architects like them were suddenly starting to operate worldwide; China was opening up to them. It all went very quickly. As a result, I could more or less say no to projects that didn’t really interest me and stick to my own style without making compromises. I’m not interested in propaganda.’ He was free not just to work without strict client specifications or blueprints, but to pursue his interest in a documentary approach, showing how such major structures are built, how people live in and around the built environment, and how architecture forms a background to everyday life.

He once said in a lecture that things only really get interesting once the architects and town planners leave and local people take over a project. For example, when people in Venezuela decide to occupy a large unfinished bank building in Caracas – abandoned by the developers because of the economic collapse of the country – and create homes in its half-finished spaces. When Chinese labourers brought in to construct some high-tech architectural masterpiece set up camp in wretched conditions around the building site: twenty men huddling around an open fire and eating out of tins, against the background of the edifice they are erecting at the risk of their lives and with no chance of their names ever being recorded in the history books. Or when people in Lagos (Nigeria) – driven by pure necessity – build a complete neighbourhood over encroaching water, creating a kind of Venice where men paddle their canoes from one shack to another. When the concept of a building gives way to the reality of human life. Circumstances change, people adjust.

In the last year he’s seen it time and again. In the spring of 2020, when he started making a few trips again – around Europe, via Mexico to the United States, in Africa – it struck him how unequally Covid was impacting on places around the world and how differently people were responding to it. Until the inauguration of Joe Biden, the United States was in the grip of disinformation and fear. ‘Half the country was

‘It gets interesting when the concept of a building gives way to the reality of human life’ scared to death, the other half thought ‘Fuck your masks, we’re having a barbecue’. The country was tearing itself apart. Mexico was interesting too: the only country in the world where absolutely no Covid-related restrictions or entry requirements have been introduced. There, it was every man for himself. It still is. The schools have been closed for a year now; only the elite can afford any kind of education. The school buildings have been plundered by gangs.’

And Africa? ‘In Africa, they’re actually doing very well. Because of their long history of infectious diseases and vaccinations, people really stick to the rules. I was in Rwanda, and there everyone is masked. On every street corner there’s a policeman checking your QR code or whether you’ve got permission to be there at that time. The population of Rwanda is almost as big as that of the Netherlands, but they’re getting only seventy cases a day. People there don’t really worry about restrictions on personal freedom. They think getting sick is the real loss of liberty.’

But what motivates this incessant travelling? I once read a suggestion by a travel writer that people who travel a lot do it not so much because they are eager to go, but because they are keen to arrive somewhere new. ‘That’s exactly it. When you step into another world, you’re completely open to it; you look at everything with new eyes; you go from one revelation to the next. When you’ve been somewhere for a while, you start to get blind spots. It’s like developing cataracts and it’s very hard to shake off. Why wouldn’t you want to travel? There’s so much to discover, so many new worlds out there.’ When he was a child, his parents never took him further away than France or Switzerland; he was twenty the first time he boarded a plane. Maybe that’s where his appetite comes from; as if he’s still making up for lost time. ‘Maybe, yes. I can get pretty restless. I’m addicted to discovering beauty.’

Addicted to beauty, or addicted to discovering it? ‘The latter’, he admits with a wry grin. ‘And actually right now is a extraordinarily interesting time to travel. Everyone’s stuck at home, and every place is different. Rather than all following World Health Organization recommendations, every individual country is trying to reinvent the wheel. Countries, states and cities are all coming up with their own rules.’

Where does the idea of ‘hopeful places’ come from? ‘I’ve always been fascinated by unique, site-specific solutions. Globalization has produced a certain same- ness, hasn’t it? A kind of monoculture that means that many countries now look identical. The same shops, the same architecture, the same way of life. What inte- rests me are those places that have embarked on a third phase. After the first phase of authenticity and the second of globalization, we are now entering a phase in which an authentic new life is emerging within the globalized setting, where the local is returning and co-existing with the international. Take Fogo Island, off the most easterly point on the American continent. In the past, before the development of general transatlantic flights, people used to fly from there, from Gan- der Airport, to Europe and vice versa. From Gander to London took three and a half hours. In the past, it was a major travel node and also the centre of a huge cod fishing industry. It was an international hub. Now it’s an airfield in the middle of nowhere. As the economy of the once busy islands waned, the young people moved away. The fishing disappeared. Life got more and more impoverished. But in the last few years, new life has emerged. Artists can now get residencies there. Splendid new buildings have appeared, all built with loving care. Experiments are being conducted with microcredits. There are little local bakeries again, and small shops. That combination of past and future, of desolation and high-end architecture, is what I find hopeful. Even in the midst of decline, new life can emerge.’

Sea Ranch in California is another example, he goes on enthusiastically. ‘Over the twentieth century, thousands and thousands of redwood trees were felled, the whole coast was stripped bare and the land lost its value. But in the mid-sixties a group of designers and architects settled there: Charles Moore, Joseph Esherick, William Turnbull Jr., Donlyn Lyndon, Richard Whitaker and landscape architect Lawrence Halprin. Working in a site-specific way and drawing on local experience, they began to restore the landscape and build distinctive homes for themselves. The result is a kind of commune and the restoration of ecological balance.’

‘It’s the fusion between local and universal that offers hope. Human inventiveness and resilience.’

He mentions Makoko, which was actually a kind of copy of Ganvie, a lake village in Benin created four hundred years ago by people fleeing from the slave trade. The epitome of a place entirely created by its inhabitants. To his mind, that’s what sustainability is all about. About a new appreciation of local solutions, of inventiveness.

‘It’s fashionable to talk about CO2 emissions, but sustainability goes further than that. It’s invariably about ‘fixes’, about technology brought from China and implemented in any part of the world, panels, batteries. But it’s not about the number of new bike tracks, for example: it’s about changing the whole car culture. And to do that, we all need to take a good look in the mirror.’ Yes, that includes him. ‘I have to be honest about it, I contribute to global warming. Each time I fly, I pay CO2 compensation under the KLM scheme, but that’s really like buying forgiveness for sins. I admit, it bothers me.’

Because his ideal lifestyle is still nomadic. It’s on the move that he’s most at peace. His future travel plans? ‘No idea. This coming year I’ll be more in America, I think. The country’s opening up again and there will be more for me to do there in the near future. There’s greater optimism again since Biden and the Democrats took power, even though the country is still completely divided.’ And, as always, he’ll be there to document it.