herman de vries

A mind-altering life

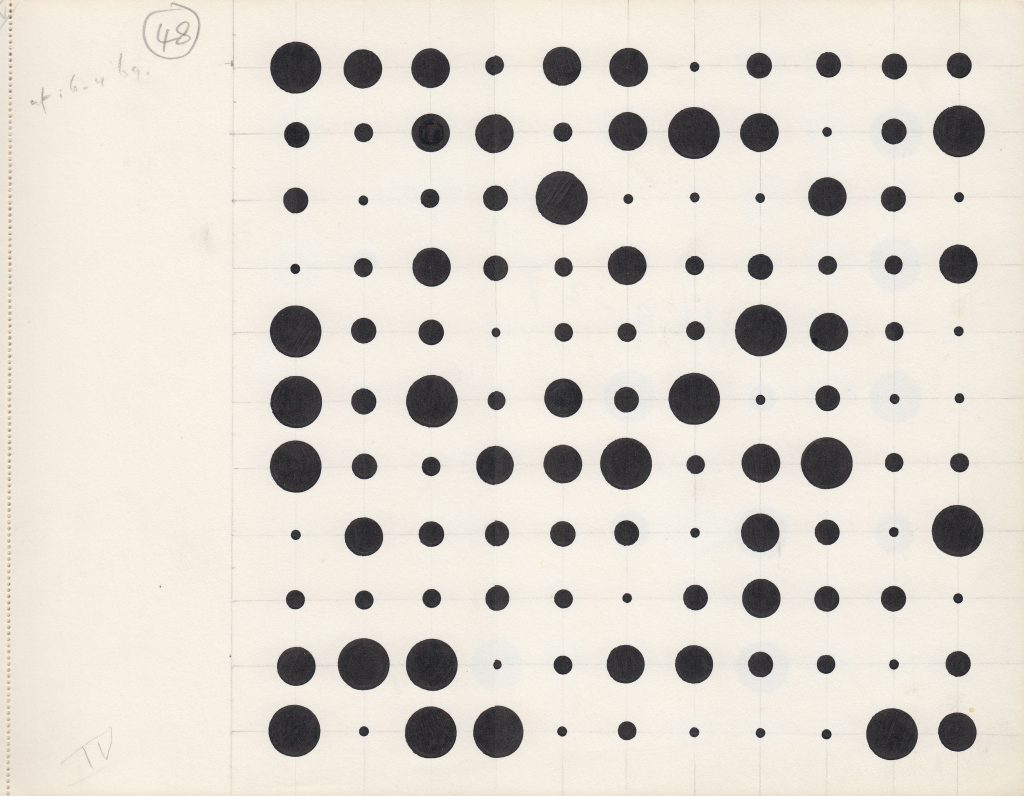

In a German village, one of the last ZERO artists on earth continues to work on his oeuvre for half a century. Without capital letters, hierarchy or fuss. From nature. ‘The greatest quality of visual art is that it can formulate something that cannot be captured in language. This allows art to make the basic principle of the world tangible: unity.’

Snow had been forecast in Bavaria – three consecutive days of it – so the photographer and I imagined a landscape like a gently white sheet. But when we arrived in Eschenau, it was raining. At first glance, the dusk-grey hills, forests, and fields made us wonder how the former biologist and artist herman de vries (b. 1931) had ended up in this place – a village of just 180 inhabitants, with a main road, a crossroads, and a hotel: the Gasthof run by the Löbl family.

‘Chance,’ he would say the next day. In 1970, de vries was on the verge of moving to Ireland. He liked the idea of living there, in a little house with a plot of land, far from the Dutch art scene and in the footsteps of his great hero, the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein. It would have marked a break from the life he had led up to the age of forty – a radical choice for a life of silence and freedom. But when he happened to pass through Eschenau that summer, there was a woman standing by the roadside. He asked her, just like that, whether there might be a house for rent nearby. Had she not been standing there, he says, he would have driven on and gone to Ireland. So yes: chance.

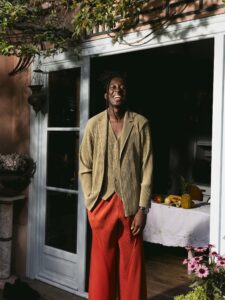

herman de vries – always lower case, because he does not believe in hierarchy, least of all in any hierarchy between letters. So: herman de vries. Now 86. An artist for 65 years. You recognise him by his silver curls, beard, moustache, bushy eyebrows, and bald forehead. He speaks softly, almost hoarsely, weighing his words in a language somewhere between Dutch and German. Or, as a friend once put it: ‘herman doesn’t speak Germanic, he speaks Hermanic’ – an open, questioning language, as it turns out, filled with poetic constructions, such as: ‘You may ask me anything. I know no mysteries.’

He lives in a former school building on the village’s main road. The school has long since become a welcoming home – a place where you immediately feel embraced. It’s hard to say exactly why, but it’s perhaps because the house makes no pretence. It is simply a place to create, to store, to gather. A living studio, or a domestic museum, without decoration or frills. Or, as his friend and researcher Co Seegers puts it: ‘There’s a sense that the artist takes himself seriously and preserves everything he’s ever made. A goldmine for any researcher.’

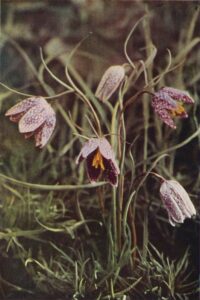

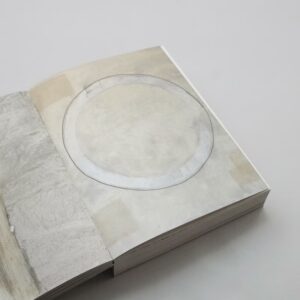

Indeed, the front room holds open shelving full of works; upstairs are archival drawers brimming with all manner of material; and in the attic are thirteen crates of letters, projects, and clippings. Nature works by de vries hang on every wall; stones rest on windowsills; twigs are collected in baskets – so that the outside is brought in and you look at it differently. And that is precisely de vries’s intention: to isolate a leaf, a rosebud, so that you can see nature again – our primary reality.

He lives and works here with his wife, Susanne Jacob, stepdaughter of the German ZERO artist Hermann Goepfert. Had he gone to Ireland, he would never have met her. Heads or tails? Heads. de vries: ‘After a failed marriage, she was someone with whom I entered into a continuous process of mutuality, now 46 years long.’

Susanne was 28 when she met herman. She had already survived a brain tumour and major surgery, which left her with lasting difficulties walking and speaking. It was herman who took her under his wing, she says, sitting in the kitchen. He travelled with her, held her hand, helped her keep her balance through all their journeys together.

Are they an artist duo? ‘Yes. No. Ja-nein.’ Perhaps it’s like this: just as Susanne uses his hand to travel, herman uses hers to work. He initiates – he finds things in nature – and she mounts them on paper. But she’s also his first and best critic. de vries: ‘Susanne makes sure things stay simple. “Is that necessary?” she often asks.’ That’s why he uses the Futura typeface: ‘A letterform that’s simple and clear.’ He uses it for everything that needs lettering – his poems, books, and the inscriptions he carves into stone in the Steigerwald.

In his three-year-old Volvo V70 (he really should study the thick manual one day to understand all the buttons on the dashboard), he drives us into his beloved Steigerwald. He has permission from the state of Bavaria to drive into the protected nature reserve – a privilege he shares only with the forest ranger. As the German landscape slides past, the soft sounds of the Arabic oud fill the car.

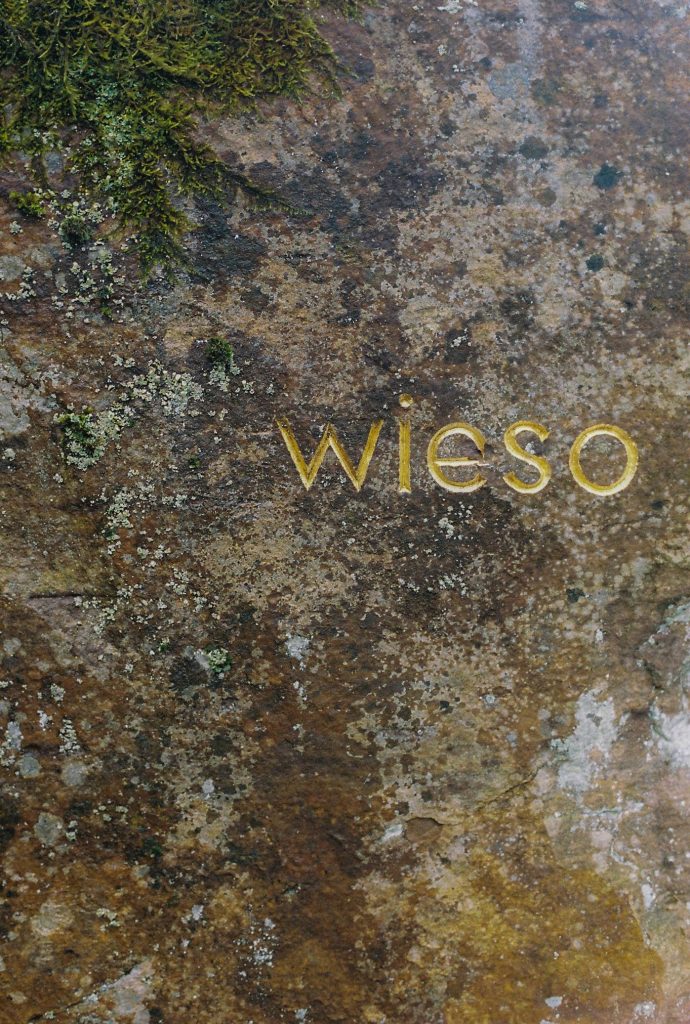

While walking, he leads the way with his Nordic walking stick, skewering wet beech leaves on its tip. At the end of the path, at the foot of the forest’s largest oak tree, lies veritas existentiae – the truth of existence.

He recounts how, over time, the ‘traces’ he left in the Steigerwald have taken on lives of their own. Stones have grown over, become mossy; even the durable gold leaf has weathered. And there was the stone bearing the inscription ambulo ergo sum, which rolled down the mountain. The boulder with the ouroboros – the snake biting its tail – was lifted and taken away by someone in a pickup truck. And then there’s the one with a Sanskrit text, which someone chiselled away. It read, he prefers to say it in English:

‘This is perfect. That is perfect. Perfect comes from perfect. Take perfect away from perfect and it remains perfect.’ de vries picked up the fragments to create a new piece at home. He discussed it with his friend Fabien Faure, professor of art philosophy in Marseille. The next day Faure called and asked to buy the work unseen, saying: ‘It remains perfect.’

This brings him to the power — and powerlessness — of language. ‘Language isolates things from one another,’ de vries says. ‘Take the word “perfect.” In language, we need to contrast it with something — “imperfect”. But that’s a false opposition. Words polarise, whereas things are in fact connected. The great power of visual art is its ability to express what language cannot. That’s why art can make us feel the fundamental principle of the world: unity.’

Everything belongs together. Everything has its place and purpose —otherwise it wouldn’t exist. If the function disappears, so does the place. In the plant world, vegetation succeeds itself: first so-called weeds colonise bare ground, making it possible for other plants to grow. This succession is a key concept in phytosociology. The ultimate stage of succession is a forest – like the magnificent deciduous one here in Eschenau. ‘It’s why I’ve stayed here all these years.’

‘But realise this,’ he says, ‘trees cannot exist without soil bacteria. Those bacteria make the ground fertile. That’s why you can’t say trees are more important than the bacteria. Hierarchies don’t exist. One grows out of the other. And that’s true for everything and everyone. We emerge from one another and are equal: all in one – one in all.’

Does this fundamental realisation have anything to do with his extreme drug experiences? ‘The whole drug thing is quite a nice biographical detail,’ de vries laughs. He’s taken a lot, and read even more. Upstairs is a comprehensive library on magical and mind-altering plants – one of the largest drug libraries in Europe – which he plans to donate in its entirety to the RKD, the Netherlands Institute for Art History, in The Hague. Drugs had a decisive influence on his life: ‘Yes, they opened my eyes to the world and left me with a lasting sense of oneness.’

Would he like to talk about it?

‘If I can talk about it.’

As a child, de vries was severely asthmatic, with attacks lasting weeks. ‘Because I was a weak, skinny boy, I had to eat porridge and drink milk all through my youth.’ Only in adulthood did he learn he was allergic. The attacks lessened, but the chronic tightness remained. He began to feel stifled in his first marriage and in his job at the Institute for Applied Biological Research in Nature (ITBON).

In 1968, he left his wife and four children. A chaotic period followed, in which the company doctor prescribed ever-increasing doses of Valium: 3, 15, eventually 120 mg a day. ‘Harmless,’ according to the doctor, but he became utterly dependent. Declared unfit for work, he took leave and left for Algeria with a girlfriend and a jam jar full of blue pills. In Algiers’ Kasbah, he lost control, wallowed in self-pity, and decided to quit. He remembers how jittery he was, how he had to pull himself up the stairs by the banister.

A few days later, he met some German car dealers who needed an extra driver to take cars to Togo. Can you imagine: ‘Withdrawing from Valium, I was driving a VW bus through the Sahara.’ They stopped in Tamentit, a village in southern Saoura. One night, a local man keeping watch invited him to sit by the fire. The gatekeeper passed around a pipe of kief, marijuana. de vries had first smoked it in Paris in 1954. Fresh off Valium, he now sat under the night sky with a mind-expanding pipe. It did him good. Drugs do him good, he says – though these days he sticks to a puff on the water pipe. ‘But that night – it was beautiful to be so open, lying on my back in the Sahara, looking at a vapourless sky filled with stars and the visible Milky Way.’

The life-altering LSD trip was still ahead of him at that point. He remembers the exact date: January 17, 1970. The day he was cured of his asthma, became a vegetarian, and broke forever with old patterns of thought and living. During that trip, he felt an acute asthma attack coming on. Such attacks were always preceded by certain vague thoughts. But never before had he been so aware of them as during that trip. In a moment of clarity, he thought: I must not think these thoughts. I need to take a different mental path. What that path was, he couldn’t say, but he took it, and it led to a spectacular, vividly colored, all-encompassing landscape. The shortness of breath disappeared – and never returned. His life expectancy had been no more than fifty years. But he’s still here, thanks to LSD.

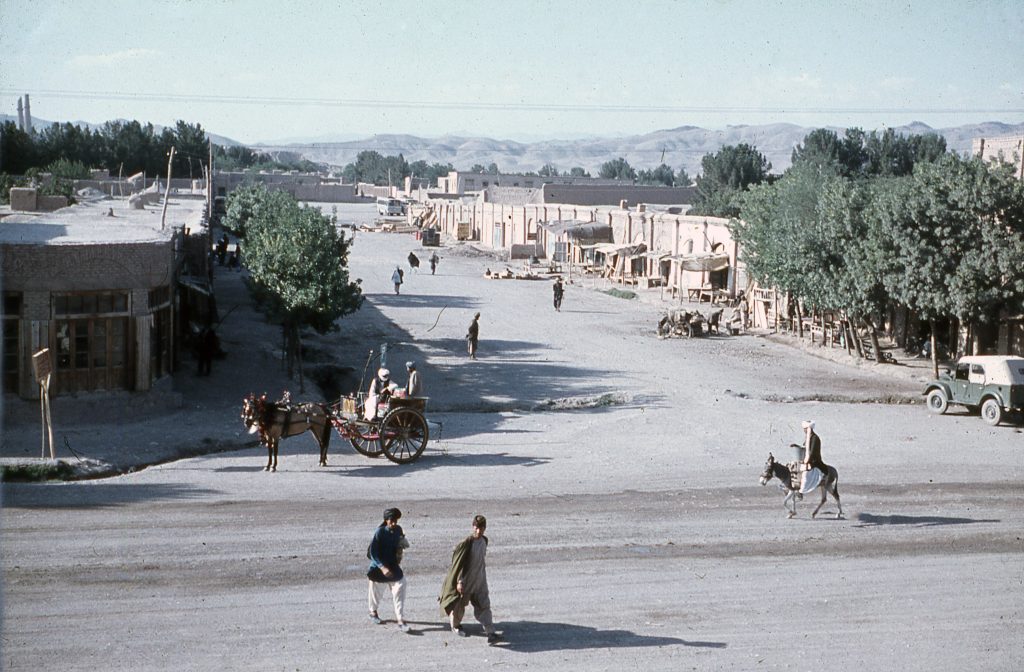

Shortly after his lsd experience, he left for the Indian Ocean with friends in spring: ‘We wanted to buy an island in the Seychelles. The island of Aride.’ Among them was one who had become a millionaire with real estate in Monaco. Who was happy to spend 65,000 British pounds on it. De vries travelled to Istanbul, Tehran and via the Caspian Sea to Afghanistan to join his friends in Herat who had already travelled ahead. In Bombay, they embarked on a ship that sailed via the Seychelles to South Africa. A seven-day journey, through a gale of wind force eight. When they were off the coast, customs prevented them from entering the country. The Seychelles did not want hippies visiting. Buying their palm island with white beaches became nothing. They could only see Aride in the distance. The Seychelles adventure did have a surprising twist, because against the friends’ strict travel agreement, de vries had a tola (14 grams) of Bombay grass sewn into the soles of his leather flip-flops at a shoemaker in Bombay. A smuggling operation that could have ended dramatically but, once successful, was greatly appreciated by all. Thus, after their down, the friends experienced a mindblowing up. De vries travelled over Kenya back to the Netherlands, and Aride was sold to the Cadbury family, those of English chocolate.

Dusk falls over Eschenau after a day of talking, driving, walking and lunching. The photographer wants to do one final round through the house, just in case, to take one last picture. ‘Go ahead,’ says De Vries. ‘Would you like a hemp cookie?’

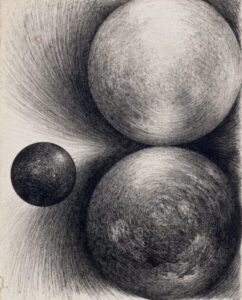

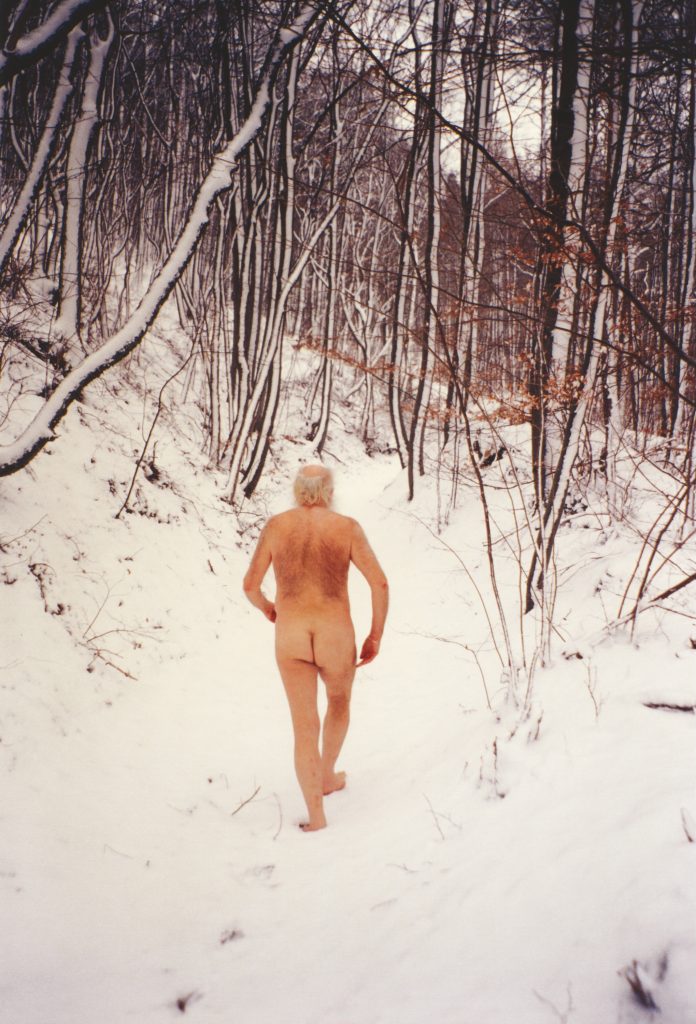

We take in the house one more time – the gong in the stairwell, the pencils on the windowsill, and the latest piece he finished just a few days ago in his bedroom. With the bed in the middle of the room, he has a free wall to work on. He says he draws best when he’s tired. Tiredness, for him, is a kind of emptiness. It often happens that late at night, already undressed, he heads quietly into the studio, free and naked, selects a piece of burnt wood, and pulls a sheet from the stack. He tapes the paper to the wall and then, without hesitation, drags the charcoal across it in a single short, fierce movement. If he were to pause to think between those actions, it would fail – of that, he’s sure. It has to happen volcanically, like a sudden eruption of personal expression. An attack. A primal cry. Done. And yes, he says, this is different from anything he’s done before – spontaneous, unlike his earlier work – but it makes him happy.

Did fear of the blank page, fear of free creation, keep him locked in a rigid working method for 65 years? He pauses for a moment, then takes a gracious detour: ‘Fear of the blank page? I’ve even left paper blank on purpose. Sheets I labelled with my name on the back. Once they even hung one of them up backwards,’ he laughs.

Did no one ever tell him it was time to stop with that nonsense? Oh yes. He recalls ‘the most delightful piece of criticism’ he ever received. In 1960, he submitted a white painting titled White Painting for the Quarles van Ufford Prize. A local art critic from Wageningen and fellow townsman wrote in Veluwepost: ‘This is emptiness squared. It doesn’t get more ridiculous than this.’ That year, the prize was awarded to no one.

He still works and walks every day – just at a slower pace. He used to walk ten kilometres a day; now he’s happy to manage 1,500 metres. Especially after his fall in late August 2017, when he jumped across a stream:

‘You go your whole life without incident, and then one day – something goes wrong.’ He didn’t break anything, but the wound became infected and kept him in the hospital for three weeks. Difficult for a man who prefers treating ailments with (mind-expanding) plants. He even asked for morphine – ‘wonderful and very fine stuff’ – but they didn’t think it was necessary.

Ah well, those physical troubles come with age. He calls them ‘obstacles’ – the five stents in his arteries, the persistent fatigue, the stiffness and shortness of breath – but what hasn’t changed is his drive to create, to travel, to experience new things. There are still so many places he hasn’t been. Island regions, for example. Australia. Japan. The Greek island of Gavdos. The tropical São Tomé in the Gulf of Guinea. He doesn’t think he’ll make it there anymore, but he’s mapped out the route:‘I can fly there from Lisbon in just six hours!’

And how does that longing relate to death? Death doesn’t worry him, he says casually. What would be nice, though, is to be given the freedom zu sterben so man sterben will – to die the way one wishes. When the time comes, he hopes to lie down and simply fall asleep. Beyond that, he’s free of ideas about what happens after death. But if he may hope for something, it’s that the end is truly the end. No reincarnation, thank you.

‘If I get the assignment to start all over again, I’ll curse in German: Scheisse, Kakke,’ he laughs – because the whole process of being raised and forced to drink milk is something he’s well and truly done with. He feels a kinship with Buddhism, though most Buddhists embrace the idea of reincarnation. He’s the type who’d prefer not to come back. A Zen master once had a beautiful expression for it, describing birth and death as ‘surfacing and submerging in the world of existence’. If that submerging simply means disappearing – well, that would be perfect: ‘Let me just slip off the face of the Earth and not be anywhere anymore.’