Guernica de la Ecologia

Interview with Claudy Jongstra

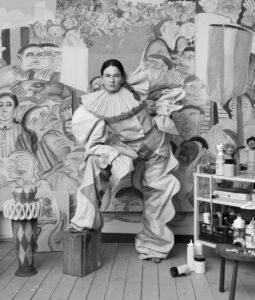

A new movement is gathering steam: Artivism. And internationally acclaimed artist Claudy Jongstra is amongst its pioneers. The scale and stature of her latest work shows that she means business. See All This presents Guernica de la Ecologia and spends a day with the artist in her studio and garden.

Thursday 28 October 2021 is an unforgettable autumn day, with light so crystal clear that long shadows extend from every berry, stake and teasel in the botanical garden at Studio Claudy Jongstra. In the early morning, the photographer and I drive north along the A5 and A7. She’s caught up in her thoughts about her unsettling time at the Gerrit Rietveld Academie in Amsterdam – apparently being unsettled makes you a better artist – and I have to keep reminding her to pay attention to the endless vistas and wide horizons of the North Holland landscape: the long lines of poplars, the parcelled-out polders under painterly skies, and the refraction of light on the waves of the IJsselmeer. In Húns, the Frisian village where Jongstra lives with her partner Claudia Busson and their two sons, we park the car on the boggy verge of their country lane. To take it up the driveway feels like an intrusion.

Behind the wall of foliage screening them from the empty pastureland stands their unpretentious white house with coral red window frames, together with an outbuilding with a cobalt blue door, a futuristic cellar and a period greenhouse. The dyeing workshop and studio barn are ten kilometres away, in Spannum.

This is the domain where Jongstra is busy constructing an ingenious self-sufficient system in which nothing exists in isolation, but everything is part of something else. The way she expresses herself in her work – the weaving and felting of wool and silk to create tactile landscapes – proves to be the foundation of her entire biotope: she weaves, felts and interconnects everything and everyone to produce an interconnected mass of people, animals and plants at the service of art.

But making art for art’s sake is not enough for her. She’s too impatient in every fibre and too afraid that both the craft skills and the necessary plants to dye textiles naturally will have died out in another twenty years’ time. She wants to make a difference. Because she can see it happening before her very eyes. The disappearance of people willing to learn craft skills. The disappearance of wild dye plants: woad, weld, comfrey, sorrel, St John’s wort, yarrow, tansy, goldenrod, horsetail and chamomile.

Her art is to be a standard bearer, gain a political voice, create social cohesion, sound the alarm and act as a rallying cry, but to do all this in soft, cuddly wool, reassuring and comforting. A new movement is gathering steam: Artivism. And Claudy Jongstra is amongst its pioneers. The scale and stature of her latest work, Guernica de la Ecologia (2021), shows that she means business.

‘A Guernica?!’ I ask, awestruck.

‘Yes,’ she replies simply. ‘As large and monochrome as Picasso’s.’

To tread in the footsteps of one of the most iconic works in the history of modern art is to invite criticism. It takes courage and perhaps even a sense of desperation. Maybe by claiming the title you can drop a pebble in the pond, or place a woollen bomb under a world order that diminishes biodiversity and fails to show love and care for the planet?

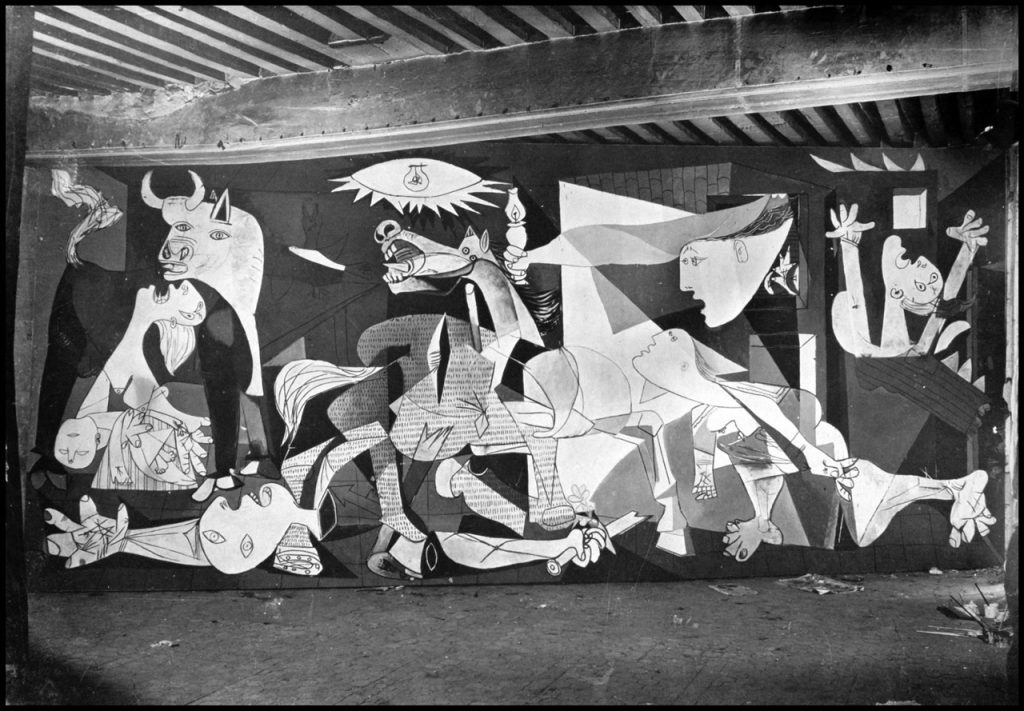

Picasso’s Guernica (1937) depicts the aftermath of the first ever carpet bombing in Europe. Carried out by German and Italian aircraft during the Spanish Civil War, the attack destroyed the Basque town of Guernica, killing mainly women and children. This crime against humanity, committed on 26 April 1937, would prompt Picasso, working in his Paris studio, to depict the chaos and devastation of the scene in matte black, white and grey house paint. He painted a horse, a bull, a dead soldier and a screaming mother holding her dead baby in her arms. Picasso was assisted by his lover, artist Dora Maar, who documented the painting’s creation and suggested its monochrome palette: as immediate and compelling as the black-and-white photography in which she herself specialised.

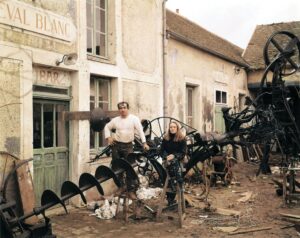

Ten years ago, when Jongstra saw the tapestry replicas of various works of art, including Guernica, at the upstate New York country home of the Rockefeller family, it was this absence of colour that struck her most forcibly. That Guernica was commissioned in 1955 by politician Nelson A. Rockefeller, a friend of Picasso, from the French tapestry weaver Jacqueline de la Baume Dürrbach. On the same visit, Jongstra saw the various logbooks containing the maker’s thoughts, colour experiments and sample pieces of weaving – evidence of the artist taking her time – and thought in surprise ‘That’s how we do it too.’

But what moved her most was the deliberate extinction of light in Guernica by the consistent absence of colour. And you know why? ‘Because of its symbolism and alchemy. Because it’s actually in black and white that the greatest colour saturation can be achieved. For example, the deepest plant-based black on earth, Burgundian Black, was achieved during the dyeing process by repeated dye baths of different colours, including one of indigo blue and one of red madder or cochineal. Imagine, dense black is the result of mixing all the colours of the rainbow!’

We sit with our back against the greenhouse in the autumn sun. A rare moment of relaxation, I know by now, after several months working together. Before us, the kitchen garden is a glorious wreckage of dying greenery lit by a sporadic flash of incandescent colour from a nasturtium flower and canopied by a backlit swarm of midges. Claudia Busson manages it by letting the plants do more or less what they like, rather than imposing her own will. Busson sits opposite us in her woolly hat and tattered Yamamoto sweater: ‘Look how she receives her guests,’ says Jongstra, in a reproachful tone but with ill-concealed pride.

She talks about the various kinds of people who visit the place. People from the art world whose shiny plastic jackets and shoes look out of touch in the garden. Gamers whose motor skills invariably make them good at spinning. Immigrant children whose enthusiasm and knowledge of nature are outstanding and who get together to wash up after lunch without being asked.

She thinks of everyone who visits Húns, and people she simply comes across elsewhere, as links in a potential chain: a growing caravan of people who can together make waves and get things moving: ‘You blow, and the community expands.’ Jongstra has a constant stream of ideas and is always keen to act on them: a mover and shaker.

She’s good at banging on doors too, when she encounters resistance, gets her syrup sold, pitches in yet again for nothing, writes a grant application or fights for funding for her latest brainchild: a weaving college in Spannum called the Phi School. She sighs, ‘These days I’m only willing to collaborate with people who are keen to move things forward, who energise you and have the gift of sharing.’

Jongstra stands up: ‘You two go on over to Spannum and see Isaac in the dyeing workshop, I’ll catch up with you there.’ She has to pick up her son from the driving test centre in Leeuwaarden, where he’s trying for his licence to ride a scooter. Successfully, as it turns out, making Jesk and his scooter a minor dissonant note in the almost cradle-to-cradle life of this community. And who can blame him? Now he’ll be free to brave the windswept lanes and the tall dikes beside the Wadden Sea.

Isaac Span is the young Frisian alchemist who experiments with centuries-old recipes to obtain the deepest colours from plants. Samples hang on the walls of the steam-filled workshop. Today he’s working on a special orange. In the nearby studio barn, the vast canvas of the Guernica de la Ecologia stands ready under a sloping roof. Jongstra crouches down to survey the area she’s working on, lays out the first patterns in carded wool, looks for sculptural effects and picks out details with handspun yarn, which will be used to do the first embroidery, emphasizing the softly rounded outlines of the flowers. We don’t yet know how it will look, but we think it will be good.

In the afternoon, we drive to the breathtakingly beautiful heathland area around Bakkeveen, where the Fryske Gea nature conservation organisation keeps the rare flock of indigenous Drenthe Heath sheep from which Jongstra obtains her wool. When we get there, it turns out that the sheep are being kept inside. Until recently, they were left out all winter but now there’s a wolf in the area.

In the dim light of the fold, where dried holly hangs from the rafters to ward off foot-and-mouth disease, the flock shuffles and snorts and the smell is of straw and sheep: ‘Isn’t that little black one something for you?’ shepherd Ko Maring asks Busson. ‘It’s a different breed and can’t keep up with the rest. If you’ve got a child seat in the car, I’ll belt it in.’

Busson takes the photographer back to Húns and I drive down the A6, along the bottom of the IJsselmeer. After recharging the Tesla in the car park of a chain hotel, I pass a row of wind turbines in the dark, while the oncoming traffic forms a string of lights like a tightly hung Christmas decoration: still so busy this late at night. I think that it may always have been the case: those who champion windmills end up tilting at them.

How do you get your voice heard? How can powerlessness be transformed into a sense that it matters what you say, think and do? We talk about it later on the phone. Jongstra tells me about the Greenland Inuit chosen by his tribe to be a runner – literally somebody who runs from place to place carrying important messages. They sent him out into the world with the message that the icecaps were melting. Nobody would listen. But this urgent message is starting ‘to resonate with us all,’ says Jongstra. Likewise, textile has been a messenger for centuries, but has been ignored and disregarded in recent decades. Because textile is a language, a carrier of meaning and symbolism. ‘I hope that the warm materiality of my Guernica will convey an invitation.’ An invitation to attend to the things around us. When it comes to caring for the planet, every square metre counts – every wisteria on the wall, every pot of geraniums on the pavement.

Picasso’s Guernica was displayed at the 1937 International Exhibition in Paris and then went on tour. It was shown in major museums like the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam (1956) and MoMA in New York, where it acted as a rallying point for campaigners against the Vietnam War in the 1960s. It was there that, in 1974, it was spray-painted in red with the slogan Kill Lies All. The painting is now in the permanent collection of the Museo Reina Sofía in Madrid.

From 1984, with the exception of the period following the renovation of the building, the tapestry version of the painting hung in the UN Headquarters in New York and served as a backdrop for many state portraits. That Guernica came to be seen as representing the conscience of the world. In early 2021, without stating its reasons, the Rockefeller family asked for the return of the totem. The wall at the entrance to the Security Council chamber is now empty. Who but Jongstra would spot the potential of that? That where there’s a gap, there is room for a new beginning.