A year in Piet’s garden

Interview with Piet Oudolf

Moving through the four seasons in Oudolf’s garden, there are days of silvery frost and burning sun. The landscape designer has revolutionised the idea of what a garden can be: a place in which to confront the circle of life, showing growth and decay in full sight. Oudolf’s reach is unrivalled and his influence exceptional. Still, it’s a one-man business. Commissions, sketches, PR and social media, he does it all: ‘No, I can’t hand things over to anyone else.

You know it immidiately, the moment you leave the everyday world (the meadows, the strips of monotonous greenery of the surrounding Dutch farmland) and enter the universe of Piet Oudolf. His large farm in the far east of the Netherlands was a ruin when he and his wife Anja bought it in 1981 but has since been expanded to form an estate boasting a comfortable farmhouse, an industrial building, a barn and a studio. You approach it via a driveway guarded on both sides by cubes of neatly clipped shrubs, now copper-coloured and brown. Driving on, you pass Piet Oudolf’s private gardens, still sunk in winter sleep and waiting for spring. All shrivelled stalks, blackened buds, skeletal plant forms, and seed heads. Decay as an integral part of nature: no more than a phase in the cycle of life.

‘That’s how it ought to be, isn’t it?’ asks Oudolf (b. 1944), sitting opposite me in his large, orderly studio. His gardens can be viewed as a multifaceted protest at the general veneration of flowers; every May, people go to garden centres to buy flowers and plants that are currently in blossom but will die the next winter. The following year, they do it all over again. Oudolf thinks that it’s all wrong. ‘The garden is a metaphor for human life, always changing and cyclical. We have our springtimes, when we are growing up; high summers, when we are in the midst of life; late summers, when we start to look back, there’s a chill in the air and we feel the time approaching to say goodbye. Then our autumns and winters. We are forced to think about the past. The glory fades from the garden; things start to decay. We humans experience the cycle from birth to death only once; in the garden, it’s an annual event. Unlike us, gardens are reborn time and again. But decay also produces life. Cobwebs, mists, insects.’

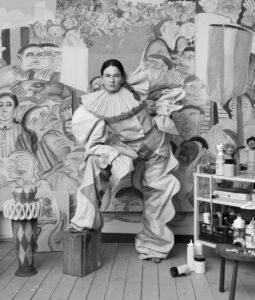

Oudolf is a striking figure: a big, broad-shouldered man in a green denim jacket. Heavy spectacle frames that can’t conceal his bright blue eyes. An old-fashioned rock ’n’ roll quiff of straight, grey hair. Between us, on the large drafting table in his studio, are fragrant cups of hot coffee from an old-fashioned drip coffee maker. Behind him, a white storage cabinet contains around a hundred rolls of his designs. On the left, bookcases overflow with gardening and plant books, their spines faded by the sun. There’s music too – lots of operas: Aida, La Traviata, Carmen… On the right, a second drafting table and containers holding dozens of drawing implements. This is the very heart of Oudolf’s world, the place where all the gardens adorning high-profile museums, institutions and luxury properties worldwide are designed and plotted. He himself spends less and less time outdoors. His own garden is managed by a retired gardener. ‘I’m an office worker,’ he jokes. When I ask if he misses the outdoor work, his response is swift (perhaps a little too quick): ‘You learn more from observing than from digging, you know. When you observe, you absorb far more information. Getting your hands in the soil is a romantic idea, but I’ve done it for long enough; it’s other people’s turn now. Anyway, I’m far too busy. All these projects. When I work outdoors these days, I soon feel stressed.’ Despite all the pressure, Oudolf works alone. He even deals with his own e-mails: an unheard-of thing for someone of his standing. ‘The work is far too personal to delegate. People tend to mail me when something’s going wrong in a garden, so what’s the point of an intermediary who won’t know what I know and can’t do what I can? No, I can’t hand things over to anyone else.’

Oudolf’s life story is paradoxical in various ways: on the one hand, he emphasises that he always felt destined (although he’s far too down-to-earth to use that word lightly) to do something ‘different’, something great. ‘I always thought I could do something other people couldn’t, I just had no idea what.’ On the other hand, he’s nothing like the archetypal artistic loner, knowing early on what he wants and retreating from the world in order to devote himself to art. Oudolf’s family ran a café and he grew up in Haarlem and Bloemendaal, on the edge of the dunes. It was a typical catering industry life: full of hustle and bustle, with hordes of people constantly around. He had a good time, hanging out with friends and thinking about the future no more than he had to. The young Oudolf had a variety of casual jobs, doing up houses, working at the fish market and in steel production – jobs he now describes as ‘cop-outs’ – and never really settled on anything. The family wanted him to go back and work in the café but he didn’t want to do that. So what did he want to do? No idea.

It all changed when he was twenty-five. He got a job in a garden centre selling Christmas trees. He must have been good at it, because the garden centre kept asking him to stay on. He worked in the plant nursery, managing deliveries to local authorities and landscaping businesses. Then he was moved to the tree nursery. And, for the first time in his adult life, Oudolf began to get really interested. He bought a book about plants and trees and began to visit gardens. He travelled further and further afield and bought more and more books. They piled up so much that he had to build shelves to hold them. So what was it that attracted him so to plants and trees? ‘It just welled up in me, a feeling that was entirely personal. It wouldn’t leave me alone. I wanted to know more and more. If something really grabs you, you respond.’

He started an apprenticeship with a landscaping company and learned the trade. Meanwhile, he attended evening classes and Anja ran a minigolf course. He got his first garden commissions. He created the garden beside the family café. ‘They liked that, at least I was doing something.’ He designed gardens in Heemstede, Haarlem and Amsterdam. But they were all private gardens and he wanted more than that: larger areas of land, open to the public. By now, his interest in plants was – as he puts it – ‘semi-obsessive’. Life was all about plants, soil, land. Every holiday was planned around visits to plant nurseries and landed estates with outstanding collections. In 1981, Anja and him left North Holland and moved to the Achterhoek, a region in the far east of the Netherlands.

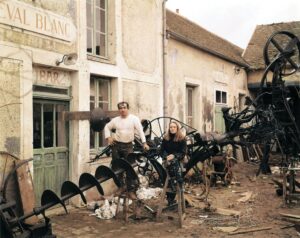

‘I was sure it was the right move, finally getting some elbowroom, but nobody in our circle understood it. Why were we going to live so far away? I was blinkered, sure, but I had to be. Otherwise, I’d never have taken the steps that I knew were necessary, even though I didn’t know why.’ They bought a piece of land with a dilapidated farm on it. ‘It was so much work. I built and laid out practically everything with my own hands.’ And it paid off: within a few years he’d developed a garden brimming with all sorts of unusual plants and people were travelling from all over the Netherlands to see it and to buy plants from him. Visitors became regular clients.

Oudolf’s design signature became ever clearer: his use of grasses gave the gardens he created a wild and spontaneous appearance. ‘The gardens are intended to look as if they have developed naturally and have not been cultivated. But we can’t use wild plants; they would crowd out the other species. We use less structured materials – grasses reminiscent of meadows – to help create that impression.’ Is there a connection between the use of coarse grasses and turf and his duneland childhood? ‘Looking back, maybe so’, he acknowledges. ‘In the past, I’d have said no. It’s only more recently that I’ve seen the connection. Lots of people owe their success to having a father who beat them. I have no traumas. I had the dunes.’

He is keen to emphasise, though, that the spontaneous appearance of his gardens can be achieved only with the right technical expertise. You need to know which plants will get along together and which won’t, how they will develop, and what they will look like in two years’ time. ‘My initial imaginative vision is spontaneous. When I receive a commission, I have all sorts of wild ideas, which I then underpin with knowledge, and later still modify when it turns out that, in practice, the plants develop differently than expected. I call my plants characters: they all have different strengths, display different behaviours, and possess individual personalities. They’re perpetually competing for light and space. Some plants proliferate, suddenly starting to take over and trying to crowd out others. You never entirely know how the competition will work out. So you sometimes have to exert control. The design is constantly changing. That’s why there must always be people with plant expertise on site, ready to intervene if necessary. And I regularly visit the gardens I have created. About every two years. Sometimes more frequently.’

An Oudolf garden begins with a list of potential plants, inspired by his original imaginative vision. That list gives rise to a rough sketch, which will be translated into neat design drawings. Then Oudolf informs his regular grower, Gerrit Lommerse, owner of the Future Plants plant nursery, what plants he wishes to use and how many of each kind he will need. This is the signal for Lommerse to start propagating, not only for the particular project, but also to ensure that the plants concerned will be available everywhere Oudolf works. Not just in Europe, but also in America, for instance, and in Korea. Because as soon as Oudolf uses a particular plant, demand for it takes off, both locally and worldwide. What Lommerse particularly admires in Oudolf, apart from his talent as a designer, is his plantsmanship. ‘He has hands-on knowledge of every step in the creation of a garden and he knows all the pitfalls. He has an unequalled knowledge of which plants go together and which don’t.’

‘Lots of people owe their success to having a father who beat them. I have no traumas. I had the dunes.’

The creation of an Oudolf garden is therefore the result of a lengthy and multifaceted process. It is years before what he sees in his mind’s eye is visible in the real world. In other words, his gardens are works of art that develop extremely slowly, like paintings in which the palette becomes apparent only over time. There is another difference between a garden and a painting: the garden continues to change; it remains a work-in-progress. When I suggest this to him, he responds immediately with ‘a third difference: it disappears. Transience is integral to the format. Anyway, I think my gardens are more like performance art than painting. Of course you can preserve their image in photos, but the garden itself will bloom and eventually die. To my mind, that only increases its beauty, because it’s like life itself.’

So he does see his work as art? He grins as if he’s caught me setting a trap for him, and perhaps I was. Piet Oudolf has the kind of down-to-earth mentality you often find in people whose work involves nature: a certain humility, as if they are aware of being just one element among many. How does such a man relate to the lofty concept of ‘art’? ‘It gets called art’, he says. ‘Very few people can do it.’ A politically correct answer, I retort. The grin vanishes. ‘Well, many people call it art. And not just the man in the street, but major figures in the art world. So I could go on saying it’s not art, as I did for a long time, but that would be rather silly. In the end it actually becomes a bit of a pose, to refuse to recognise a general consensus.’ The grin returns, slowly: a little tilt at the left-hand corner of his mouth. ‘We’re all looking for a narrative that elevates what we do above mere craftsmanship. And I think I’ve earned the right to believe in that narrative.’

He certainly has, through his countless renowned designs, of which the High Line in New York is perhaps the most conspicuous. Other high-profile designs include the Dream Park in the Swedish town of Enköping, Oudolf’s first ever commission for a public place. Created in 1995, it is often described as his breakthrough. Then there is the garden of the Hauser & Wirth art gallery on Menorca, a project to which he regularly returns because the heat makes it so difficult to maintain. Or the garden of the Noma restaurant in Copenhagen, where the challenge was its elongated shape: ‘I didn’t have the luxury of space to tell a story; the garden was a long, narrow strip that had to be interesting all the time; every view had to be spot on.’

Oudolf has recently begun work on his first Asian garden, in South Korea. ‘The Koreans had been on at me for ages to come and make a garden there. But I kept fending them off. I was too busy. And anyway I was a bit afraid of it. The bigger your name, the more you have to lose. And when I try to keep things simple, I’m always overcome by my imagination and ambition; simple is just not my thing. I can’t get away from myself. And then there was the difference in climate. I found a garden in Spain difficult enough, so how should I know what plants would thrive in Korea? But they were persistent. In the end we set up a test garden. For two years, we monitored what grew there and what could be exported. I also worked with a number of plants with which I had no experience: a variety of eupatorium and a kind of aster I’d seen there. It did me good to see that there’s still so much to learn and discover, even for me.’

How can such ambitious long-distance projects be reconciled with ideals of ecological sustainability? To minimise their carbon footprint, Oudolf and his nurseryman Lommerse strive whenever possible to use local growers (instructed by themselves). ‘That way, you embed the knowledge and expertise at a local level too’, Lommerse says. ‘And it gets people personally involved in the implementation of the design.’ They also try to include native species. But that’s not always easy. ‘Not all native species are properly described and tested’, Lommerse explains. ‘Or they’re not available. Sometimes they are simply not cultivated, or not suitable for cultivation. They look wonderful growing wild, but in a complex plant community like the ones Oudolf creates they are likely to behave too aggressively. When maintaining and revising planting schemes, native species can often play a greater role.’

Alongside the many designs Oudolf currently has in hand, there is now a Piet Oudolf Collection: a selection of plants available to the general public and guaranteed to be long-lasting and sustainable. ‘Lots of beautiful plants are unavailable to ordinary people. That’s a pity, don’t you think? We have a great collection, so why not make it accessible?’ When I call the plan ‘generous’, he protests. ‘I’m giving a lot away, but it costs me nothing. All my knowledge is available for free, I have no secrets. This is my passion and I want to share it. It gives me great satisfaction when other people are able to enjoy the same things I do, so you could just as well say it’s selfish. Gardens shouldn’t be shut away where nobody can see them. Let everyone start their own garden.’

Here, once again, Oudolf’s paradoxical side is on display: ‘It isn’t a revolution. People aren’t going to change the way they act. For the last forty years we’ve been trying to make the world a better place and do you have the impression it’s produced a radical reorientation? It’s true younger people are more eco-aware than their elders; they recognise the importance of greenery in public spaces. There is more of it, but not enough. If you generalise, if you stand back and look at the world, you quickly become defeatist and see what you do as insignificant. But if you zoom in to the personal level, you see that there is hope. You have to go on believing that you’re doing some good. The trick is to see that, on the one hand, it’s a big bad world, while on the other the world is small enough that even your little garden or your one plant can make a difference.’ At the end of the interview, we share a meal – two brown bread sandwiches each, with cheese and sausage – served to us by Anja. Then he asks if I’d like to see the garden.