Back to the Future

A conversation with Lidewij Edelkoort

To truly see things, you must live on the edge of society, maintaining a distance from what you seek to comprehend, Lidewij Edelkoort says. The internationally acclaimed forecaster predicts an era in which creativity takes center stage, heralding what she calls the Age of the Amateur: ‘Whether it’s through play, dance, song, culinary arts, gardening, craftsmanship, or visual arts, creating by hand has always brought us joy, purpose, and pride.’

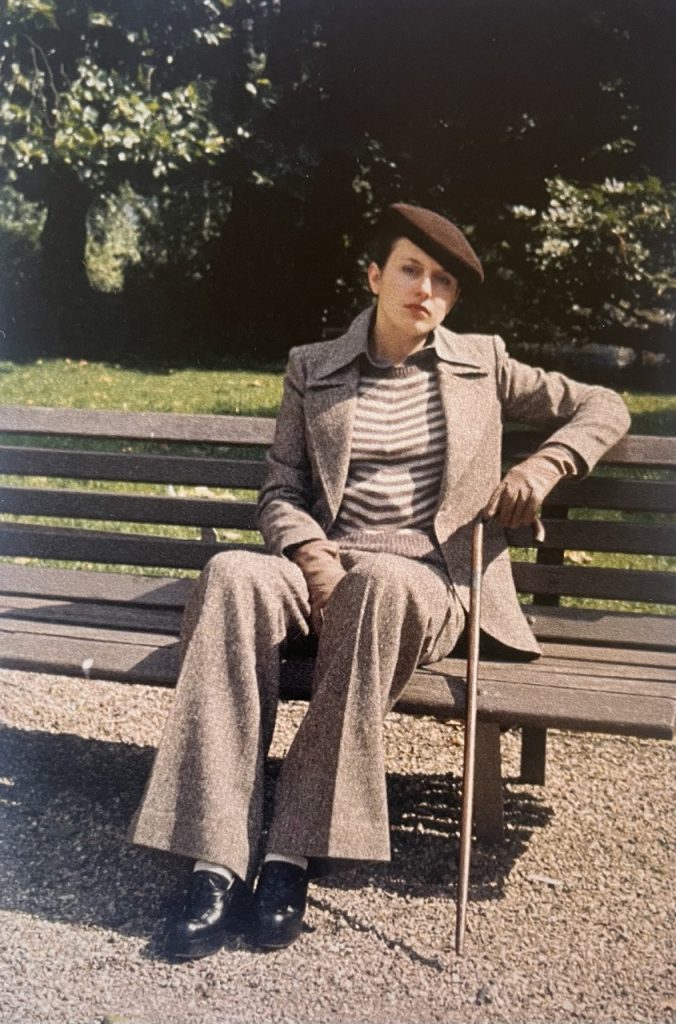

What does time represent to someone who predicts the future? And how do you become a pioneer, a time traveller, an interpreter of things that lie ahead? Trendforecaster Lidewij Edelkoort (b. 1950) increasingly finds herself living in the future she once foresaw. And more than once she has wondered if she was right with her visions of a world-conquering colour palette, a new silhouette, a tendency, or a change in our societal preferences. Since founding her company Trend Union in Paris in 1986, she has not only predicted the future but also played a role in shaping it. For example, when Madame Edelkoort declared pink was on its way, the future turned pink. In 2003, Time Magazine honoured her as one of the twenty-five most influential people in the fashion world. In 2012, she received the Culture Fund Prize in the Netherlands, and by the spring of 2024, she was listed among the fifty most influential women in architecture and design by the prestigious magazine Dezeen.

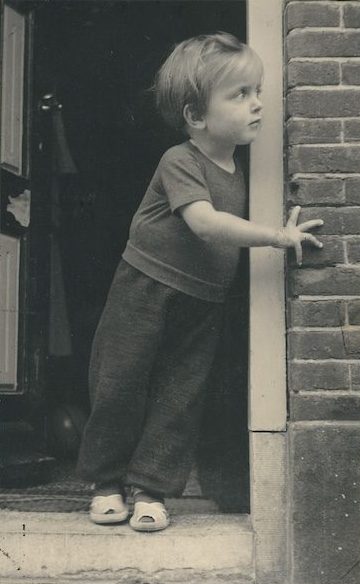

Meanwhile, seventy years separate the remarkable eminence grise and the toddler she once was, captured in a childhood photo: a girl dressed in a knitted sweater, jersey pants and tiny sandals, her gaze fixed on the distance with an open, observant demeanour. It is one of the things that immediately strike you when first meeting her in her home on the coast of Normandy, that unwavering, curious gaze in her light blue eyes.

How do you develop a way of looking and feeling that enables you to register what changes are on the horizon?

To truly see and interpret things, you must live on the edge of society, maintaining a distance from what you seek to comprehend. This detachment is essential. That’s why travel is crucial – it offers freedom from one’s own culture and allows for the exploration of new ones. Wherever I go, I strive to observe the unusual, as it’s often the exceptions that foreshadow the future. The future unfolds through thoughts, actions, and creations of certain individuals, initially embraced by a small group before rapidly proliferating into a trend

What defines trends? Where do they originate?

A trend emerges from a collective consciousness that transcends individual minds.

Our thoughts extend beyond our brain and coalesce into a shared field of contemplation. When this field reaches critical mass, with an important portion of people thinking along similar lines, it becomes a shared movement from which we all draw inspiration. When this mass approaches around 20% it becomes commonplace and solidifies into an acknowledged phenomenon.

Like a vast cosmic database?

Yes, essentially all our experiences, thoughts, and desires are swirling around, waiting for someone to grasp them. Some individuals are more adept at catching these insights earlier than others. There’s almost always someone who expresses a desire, such as “I really want a red sweater,” and then, lo and behold, two years later, it becomes a reality. We all have these moments of foresight. But it takes dedication and rigorous training to turn this intuition into a profession.

How do you cultivate that intuition?

By listening attentively. In the beginning I sometimes used to ignore that inner voice, only to realize later that I was wrong. Therefore, I made a conscious decision to wholeheartedly trust my intuition. By remaining committed, you start receiving instinctive signals. It could be a sudden revelation about a colour, a sculptural form, or deep insight into emerging social dynamics or pivotal societal shifts. It’s incredibly nuanced and at times I even feel it physically. My shoulders yearn to broaden, or my legs might long to elongate. And no, this is not about my personal desires, it is more like an internal cue. Speaking of which, it’s high time for a trend of longer legs.

Legs, you say?

Yes, long legs. But first we’ve got to address the issue of breasts because, obviously, that’s a major concern.

Breasts are problematic?

The obsession with constantly enlarging and enhancing breasts is detrimental to both our health and fashion. As they become the focal point, they cause the shoulder lines to droop backward, which becomes a strange silhouette. It’s just a weird fixation with breasts.

Why is that?

I believe it can be traced back to the AIDS epidemic of the late 80s and 90s, which decimated many gay individuals in creative fields. Entire communities from art, dance, style, makeup, and fashion were affected. Consequently, these industries fell under the influence and tastes of conventional heterosexual men. Suddenly, high heels and handbags were back in vogue. We had made strides to move away from them, since we had pants and jackets with pockets, boots, shirts, and then, abruptly, they vanished. The dress was back. Another peculiar shift was the taboo on nipples. Did you know that’s why bras became so heavily padded and moulded? However, I observed a reversal during the recent fashion shows of 2025, where alongside the return of salacious pubic hair, the nipple is making a comeback.

Did you always have that sense of what’s about to happen?

I’ve always been a natural inventor. At the Fashion Academy in Arnhem, I wasn’t the best at drawing or designing, but I had a knack for advising my peers on how to best utilize the fabrics at our disposal. Quickly I became the art director for the group. Even as a child, I didn’t need kindergarten because I entertained myself at home. In my toddler years, I yearned to emulate adults, constructing a cardboard house in the corner of the living room, complete with a cardboard record player and makeshift records, which would play music to my ears. I even crafted a briefcase, obviously also from cardboard. At that time, in the 50s, I loved to wear my cherished nightgown, stitched from used linen flour sacks from just after the war, handed down to me from my older sister. Despite its wear and tear, it was washed to a delightful softness, and made me feel like an angel. That gown also provided me with a sense of security, dispelling any fears – I had an active imagination and dreaded nocturnal encounters with wolves. This sense of security is one of the most remarkable aspects of clothing, offering us both physical and emotional protection. Furthermore, the way you dress can become a manifestation of self, commanding respect, appreciation, and sometimes even adoration from others.

How did you become a central figure in the fashion world?

My breakthrough in the fashion industry came after my time at the Dutch department store De Bijenkorf, where I was a stylist. In 1986, I founded the collective Trend Union with some friends in Paris. We created trend books and held international trend presentations. Nowadays, it’s all done via zoom, but back then, we toured Europe, America, and Japan, where we had many clients and went shopping for textiles. It was a time of great splendour. However, those days are gone. Now, people lack time to engage in such endeavours, they are less inclined to move somewhere and are often reluctant to invest in information. Consequently, the fashion landscape has undergone profound transformations.

Fashion today often relies on marketing, employs artificial intelligence for design, and bases all decisions solely on data. This approach is detrimental to fashion because it perpetuates the replication of past successes rather than fostering innovation. Nowadays, designers at famous fashion houses are constrained to reproducing last year’s bestsellers and translating current trends to their collections, leaving minimal room for originality, limited to some ten pieces of clothing. Investments in the fashion industry are treated as investments in heavy industries that don’t move forward, while fashion thrives on evolution and change. Consequently, the fashion sector has stagnated. This current lack of substantial change has created a precarious situation, where sudden shifts can result in significant missteps. A recent example is the sudden disappearance of streetwear, leaving us inundated with surplus hoodies and puffer jackets. And the same is happening to all the discounted sneakers, caused by a sudden surge in demand for moccasins and lace-up boots. I have never witnessed such an unprecedented and drastic shift before.

Can you explain that radical halt, for example, using those sneakers?

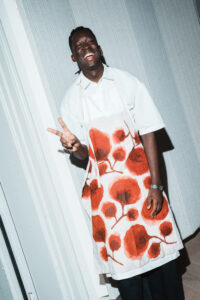

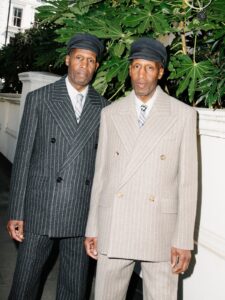

It’s all intertwined, really. The Black creative community, rooted in hip-hop and rap culture, pioneered brands like Off-White and Supreme. When designer Virgil Abloh ventured into Louis Vuitton territory, it ignited a grandiose, flamboyant movement, with Balenciaga joining in with even more oversized stuff. Even sneakers followed suit, expanding, and spilling out. I’m referring to the entire gentrification of street fashion, where many people made much money. However, Abloh’s unfortunate passing marked a sudden end to it all. His death wasn’t the cause, but rather the catalyst for its abrupt conclusion. Suddenly, those individuals sought vintage shirts and shoes. The pandemic played a role too, as people grew weary of lounging in shapeless clothes at home. Post-lockdown, a collective desire for structure and tailoring emerged

Does sustainability play a role in that?

That’s an enormous problem because it’s essentially unregulated. And progress in this area is very slow. Only occasionally do we see initiatives, at houses like Hermès, that truly care about sustainable practices. And new brands like Bode that only collect and recycle antique fabrics are also making strides in the right direction. Additionally, there are young people who repurpose old garments to create new ones, but collectively, these efforts represent only a fraction of the industry. It’s deeply concerning, but there is hope, as there’s still one entity capable of affecting change, which is the consumer. By adopting an alternative perspective towards our wardrobe and way of dressing, we can make a difference. Treating our clothes like curated art collections – valuing frugality, care, and preservation – can bring transformation. With just one thoughtfully chosen new piece, endless combinations and variations can bring new life to our existing closets. This is where the consumer becomes the collector.

Beyond fashion, many systems are in need of a radical overhaul, a reimagining. How do you envision the future on a macro level?

You know who inspire me? My students at the fashion institute Polimoda in Florence, where I designed a master’s program called From Farm to Fabric to Fashion. Since nobody remembers where materials come from and how they are produced, we’re returning to the roots of textiles in our curriculum, literally going to the farm. Students engage with fibres, spinning yarn from wool and flax, learning how to weave, knit, and embellish, and they only delve into fashion design at a later stage. I’ve witnessed a remarkable transformation in the students – not just academically, but even physically. Their inner passion glows and makes them more beautiful. Sadly, they represent just a small fraction of aspiring designers. But what also gives me confidence is my experience with the World Hope Forum that we founded during the pandemic.

Every month we visit another country online where an ambassador curates a program of speakers that care for people, animals and the planet. They lead the way to creating a new world. It is a free forum enjoyed by thousands of people. For humanity as a whole, I foresee colossal upheaval. In roughly fifteen years, AI will likely dominate most aspects of our work. This implies that from now on we need to contemplate our identity in a world without traditional employment. With the disruption of earnings and daily routines, our educational systems must reinvent themselves to teach differently and to keep up with the world. What will define us and give meaning to our existence on this planet? While some days evoke a sense of impending doom, through my optimistic lens, I forecast that an extraordinary role will be reserved for creativity. Whether it’s through play, dance, song, culinary arts, gardening, craftsmanship, or visual arts, creating by hand has always brought humans joy, purpose, and pride throughout history. I call this the Age of the Amateur

For now, Lidewij Edelkoort continues to do what she’s always done: moving and working at a fast pace, making things possible for as many people as she can. How does she manage to keep up with that? ‘I actually feel like I’m getting mentally younger,’ she says. That’s beautiful. While she propels us into the uncertain future in yellow she herself travels back in time on those timeless sandals of hers.