Visionary Women

Who Shaped Art History

In a world where art history has traditionally celebrated male patrons and dealers, a remarkable group of women quietly revolutionised the art landscape of the nineteenth century. These visionary collectors and dealers – once relegated to footnotes in museum catalogues – were instrumental in shaping artistic taste, supporting emerging talents, and building collections that would later form the cornerstone of major museums worldwide.

The Netherlands Institute for Art History (RKD) has unearthed some of these extraordinary stories of forgotten Dutch pioneers through meticulous research, revealing a vibrant network of women.

1. Sara de Swart (1861-1951)

After her mother’s death, Sara de Swart left her hometown of Arnhem for Amsterdam, where she quickly became part of a group of young artists and writers known as the Tachtigers. She took modelling classes and trained as a sculptor. Unmarried and queer, Sara was a striking figure in the group of friends. She regularly purchased works from her friends, followed by acquisitions from French artists Odilon Redon and Auguste Rodin. As early as 1889, De Swart had personal contact with Rodin and was one of the first Dutch collectors of his work.

Together with her partner, the needle artist Emilie van Kerckhoff, de Swart lived in Villa De Hoeve in Laren and travelled to Asia and Egypt. In 1914, it came to light that De Swart was financially ruined. She then had a few of the artworks in her possession auctioned off, but it was not enough. The couple fled to Rome and later settled in Capri, where De Swart died in 1951 at the age of 90.

2. Helene Schemel (1850-1907)

In the autumn of 1893, Helene Schemel founded an art gallery on the ground floor of her home in The Hague. Her husband, the artist Adolphe Artz, had died three years prior, and apart from caring for their two young children, she now also had to support herself. Since she already knew many artists personally, starting an art gallery was the obvious choice. After running the ‘Kunsthandel Mevr. De Wed. Artz-Schemel’ for several years on her own, Schemel remarried in 1897. The business was then renamed Maison Artz and moved to a different location. Schemel sold paintings, watercolours and drawings by the artists of The Hague School and their followers to Dutch collectors. Their work was also in great demand in the United States, which was convenient because Schemel liked to travel and made several crossings.

3. Gerarda Henriëtte Matthijssen (1830-1907)

Matthijssen initially worked as an artist and drawing teacher in her hometown of Leeuwarden. In 1878, she opened the Salon for Modern Art in Leeuwarden. This was her latest venture after starting a successful photography studio ten years earlier. The art gallery regularly held exhibitions of works for sale, including those by artists such as Hendrik Willem Mesdag, Frits Mondriaan (the uncle of) and Laurens Alma Tadema.

4. Anna Christina van Zegwaard (1832-1913)

After turning fifty, Anna Christina van Zegwaard from The Hague embarked on an ambitious collecting journey. Following the death of her parents and six siblings, she became the sole survivor of her family and inherited the entire family fortune. Her collection would eventually encompass 161 watercolours, 37 paintings and six works on paper, primarily by Dutch artists. Van Zegwaard – who liked to paint and watercolour herself – also acquired works by nineteenth-century Italian artists and singular pieces by English, French, Norwegian and Russian artists. She likely purchased these during her travels, on which she was accompanied by a personal chamberlain.

The sums she invested in watercolours varied considerably – from 200 guilders to the substantial 4,000 guilders she paid in 1901 for a watercolour by renowned Hague School artist Jozef Israëls. Van Zegwaard lived on the prestigious Koninginnegracht in The Hague, where she preserved her watercolours and works on paper in large albums. Following her death, the collection was auctioned and the artworks became dispersed. Thanks to the catalogue from that auction, the composition of her collection can be reconstructed today.

Regrettably, no personal documents or photographs of her survived. In her will, she specifically instructed: ‘I desire that all family portraits, whether in oil or photographies, shall be destroyed, as well as the painting work made by myself.’

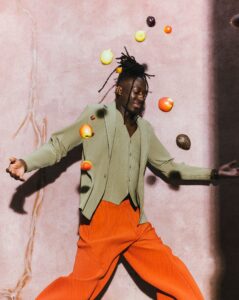

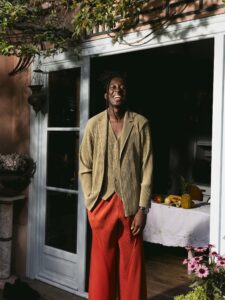

5. Griettie Smith-van Stolk (1860-1941)

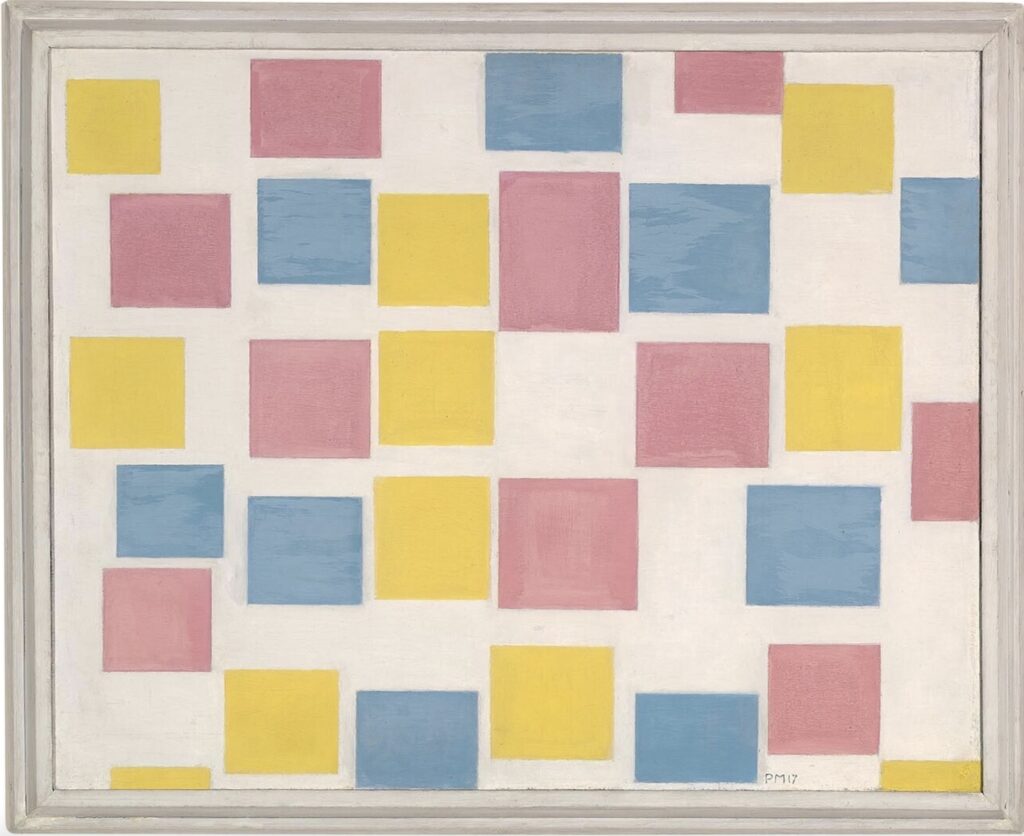

Griettie Smith-van Stolk was raised surrounded by art: her father, Adriaan Pieter van Stolk (1822-1894), was an art collector who provided financial support to the artist George Breitner – who she also posed for (see above). Smith-van Stolk was an accomplished artist in her own right. She created watercolours and drawings depicting her surroundings and daily family life, although she chose not to exhibit these works publicly. She amassed an impressive art collection comprising nearly 200 objects, including 150 paintings. Among these were innovative works by artists such as Piet Mondriaan and Bart van der Leck. Most of her acquisitions were made through the art adviser H.P. Bremmer. Smith-van Stolk was also a patron to several artists. A number of works from her collection eventually found their way into Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen in Rotterdam.

6. Adriana Johanna van Boekhoven-Leijdenroth (1840-1917)

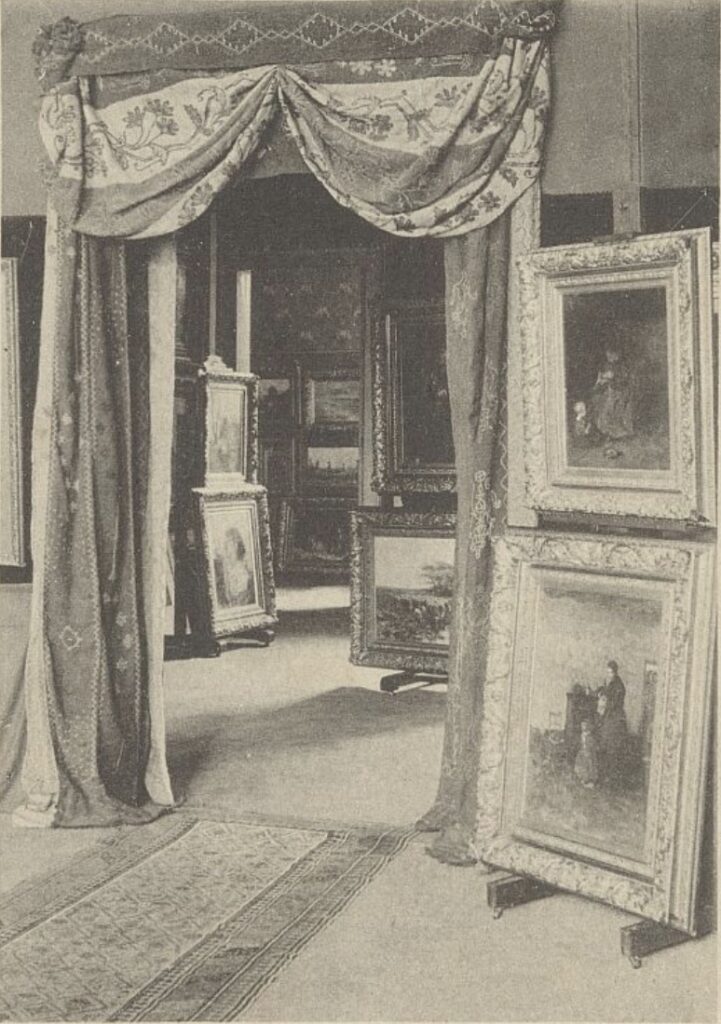

Born in The Hague, Adriana Johanna Leijdenroth was the daughter of a hat manufacturer. In her early thirties, she enrolled as a student at the Academy of Fine Arts in The Hague. Only two paintings by her hand are known (both in the collection of the Centraal Museum Utrecht), and it appears she never exhibited her work publicly. At the age of 43, Leijdenroth married Jacobus van Boekhoven, who was Utrecht-born and 30 years her senior. He had founded a successful printing business. When van Boekhoven died in 1897, she inherited both the printing house, which she would subsequently run with a co-founder, and total assets exceeding 250,000 guilders. Following this inheritance, van Boekhoven-Leijdenroth commissioned a new villa in Utrecht, designed by the renowned architect Eduard Cuypers. No expense was spared for the sumptuous interior of the house, which featured a dedicated paintings room. The villa’s other rooms were also filled with works of art. A year after her death, her impressive art collection – comprising 66 paintings and nearly 100 works on paper – was auctioned.

7. Louise Thurkow-van Huffel (1900-1987)

Louise van Huffel grew up in Utrecht, where her father owned a well-known antiquarian bookshop. After working for the municipality of Utrecht for some time, she married engineer Christianus Theodorus Franciscus Thurkow (1882-1970) in 1933. Ten years earlier, Thurkow had begun collecting mainly Dutch paintings from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. After his mother’s death, Thurkow inherited not only a large villa at Plein 1813 in The Hague, which had been in the family for generations, but also the means to start collecting. Paintings, such as Salomon de Bray’s Jael, Deborah and Barak [or Adriaan Coortes’ still life], were given a place in the house that Thurkow had redecorated a few years before his marriage. It is not yet clear how the couple came to make their purchases and whether Van Huffel had different tastes from her husband. In any case, she was involved in documenting the collection. This resulted in a catalogue she compiled in 1962, which she created especially for her husband’s 80th birthday. In addition to that catalogue, she also compiled three albums with photographs of the paintings and the interior, so that we now know how and where the works hung in the large house. After her husband’s death in 1970, Van Huffel made no further purchases. In 1978, she moved to a smaller house. She kept some of the artworks with her, while others were donated to museums, auctioned or distributed among the family. After her death in 1987, she left thirteen paintings to the Dutch State.

8. Josephina van Baaren (1890-1959)

Josephina van Baaren and her brother Lambertus (1888-1964) assembled a collection of more than 400 paintings and drawings by French and Dutch artists from the nineteenth century, as well as Japanese prints and silver. Their father, who started out as a carpenter-contractor and appraiser, developed into an expert in real estate. The Van Baaren siblings inherited the fortune, and Lambertus expanded it even further. This enabled them to build up this extensive art collection between 1925 and 1964. They mainly bought from art dealers in their hometown of Utrecht, but also in The Hague and Amsterdam. Their first purchase was a series of Japanese prints from A.J. van Huffels Antiquariaat in Utrecht. Their purchases were strongly influenced by the art educator H.P. Bremmer. Both unmarried, Josephina and Lambertus remained together throughout their lives. They collected and lived together in their childhood home on the Oude Gracht in Utrecht. After their death, the house was opened to the public. Since 1980, the art collection has been on long-term loan to the Centraal Museum.

9. Kora Cosman (1897-1964)

Kora Cosman was born in Amsterdam and was the daughter of lawyer and poet Mr Herman Cosman (1862-1921) and Dina Hyacinthe Kann (1867-1919). Although she had graduated with flying colours from the Amsterdam Gymnasium, she went on to train as a nurse. Her teacher Helene Melk (1888-1970) was one of the first nursing teachers in the Netherlands. She would eventually become her life partner. After a trip through the United States in 1928, the couple settled in Blaricum. Cosman already had a collection of several Dutch nineteenth-century paintings and drawings. She probably inherited most of the works from her father. She also added a number of her own purchases, such as drawings by Marius Bauer, which she bought from the Amsterdam art dealer E.J. van Wisselingh & Co. During the Second World War, Cosman, who was Jewish, had to go into hiding. Cosman and Melk also took in a number of people in hiding. Between 1940 and 1942, she sold a number of works of art from her collection. According to tradition, Cosman was ‘excellent in hiding, cautious without panicking, calm and cheerful, focused on her household tasks and full of interest in the outside world’. (Romein-Verschoor, p. 46) After the war, she lived in Baarn. Upon her death in 1964, she left several works of art, including works by George Breitner, Gerrit Dijsselhof and Willem Maris, to the nearby Singer Museum in Laren.

The RKD is examining the underrepresented role of female collectors in the Netherlands between 1780 and 1980. The results of the research will be described in a digital publication in the RKD Studies series, which will be published in the autumn of 2025.