The Great Goddess

Essay Griselda Pollock

As one of the most influential voices in feminist art history, Holberg Prize-winner Griselda Pollock lends her insights to our Pretty Brillian issue on Goddesses. Pollock has transformed the art historical canon and served as ‘a beacon for generations of art and cultural historians’. For See All This, she explores how we can use the term ‘goddess’ to examine the long history of human imagination.

This story lives where art and insight meet.

We invite you to enter the world of See All This — Join those who journey deeper.

This essay is included in See All This #38. Order a copy here.

Recent stories

-

![]()

Article •

The one essential ingredient: Editorial #40

-

![]()

Interview • No. 40 •

Mory Sacko: A Remarkable Recipe

-

![Carrie Mae Weems, Untitled (Woman with Friends) from The Kitchen Table Series, 1990, platinum print]()

Article • No. 40 •

The Dinner Party: How shared meals can change your life

-

![Salvador Dalí and Gala’s fundraiser party A Surrealist Night in a Surrealist Forest, 1941, Monterey]()

Article • No. 40 •

5x Hosting Like an Artist: From Judy Chicago to Salvador Dalí

-

![Copper Terracotta Kadai and Tokri Chafing Basket Small]()

Column •

Li’s Forecast #6: Pots and Pans

-

![Adrián Villar Rojas, Untitled (From the Series The Language of the Enemy), 2025. Installation view, Audemars Piguet; Le Brassus; Switzerland © courtesy of the artist, Aspen Art Museum, Audemars Piguet Contemporary and Kunstgiesserei St. Gallen. photographed by Jörg Baumann]()

Article •

Adrián Villar Rojas at Le Brassus: Through Layers of Time

-

![]()

Column •

BREAKING #290: A dizzying web

-

![]()

Guide •

Seven in a Week: In 7 exhibitions to Madrid

-

![]()

-

![]()

Column •

BREAKING #289: A six star review

-

![Grace Wales Bonner]()

Article •

Grace Wales Bonner at Hermès: Not just a headline

-

![]()

Column •

Li’s Forecast #5: A glazed pig as the emblem of an economy

-

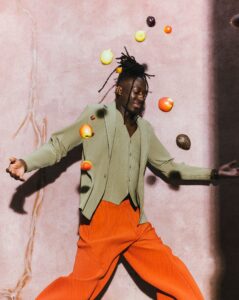

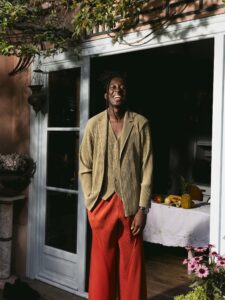

![Mory Sacko]()

Article •

Mory Sacko: Guest Curator of See All This’ anniversary issue: Cooking is Caring

-

![A spread of the See All This Magazine]()

Article •

Mercur Award Nomination: Media Brand of the Year 2025

-

![]()

Column •

Asma’s Beauty Case: ‘Art lives in the small things’

-

![]()

Column •

BREAKING #286: A good acorn year

-

![]()

Column •

BREAKING #285: ‘Do you keep sheep?’

-

![]()

Column •

BREAKING #283: Mory Sacko

-

![]()

Column •

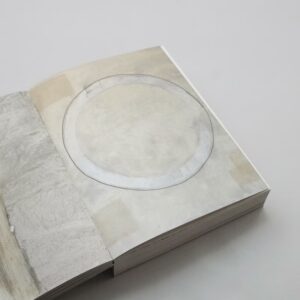

Li’s Forecast #4: The Book Maker: From Homo Sapiens to Homo Luminous

-

![Bar Magritte Hotel, Amigo, Brussels]()

Guide • No. 39 •

Brussels Bound: A city guide