The Future Library

Katie Paterson and the library that is yet to come

A forest where the voices of a hundred writers whisper in a library that is yet to come. An interview with artist Katie Paterson about The Future Library, which will open in 2114.

At the edge of a Norwegian forest grows The Future Library. You can already wander there, but no book is to be found yet. Over the next century, a hundred authors will write a manuscript for this place, to be printed in 2114 on paper made from the thousand spruces currently growing. This breathtaking anthology is the work of visual artist Katie Paterson, who intertwines the vastness of time and the universe with our ability to imagine distant realms.

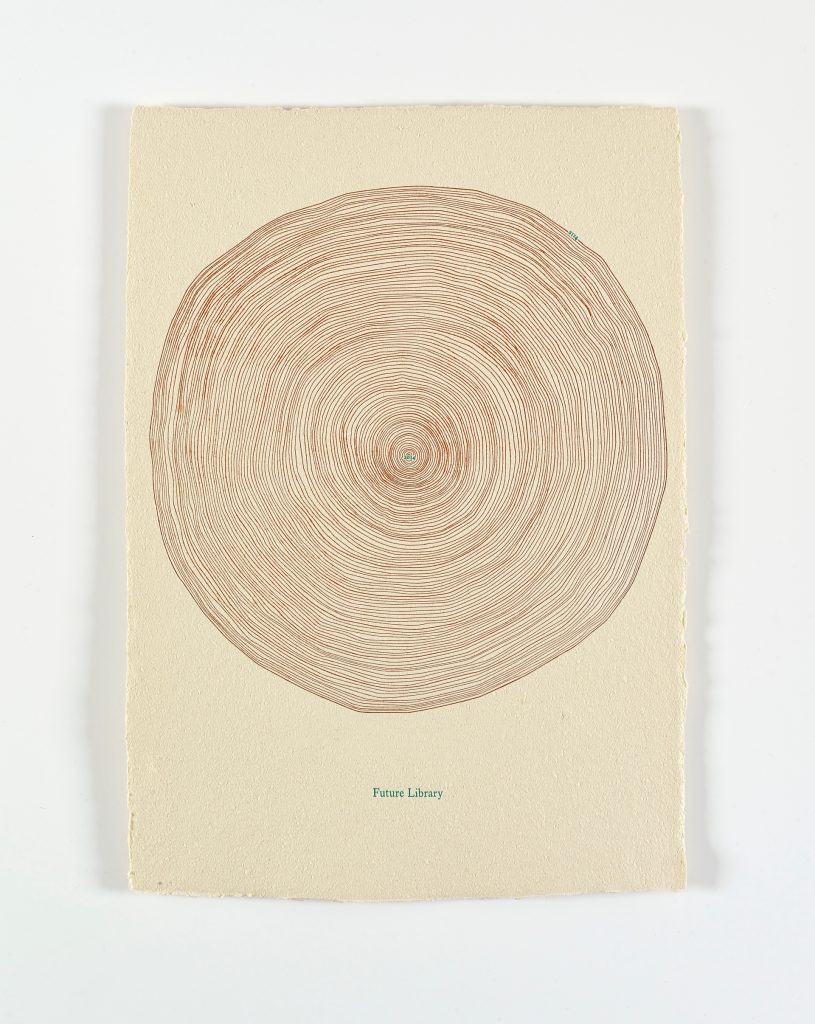

Katie Paterson (1981) lives and works in Glasgow. She has previously mapped dead stars, broadcast the sound of melting ice caps on the radio, and shot a meteorite back into space. Her work explores various dimensions, making bold leaps from the edge of the universe to the title of an unread saga. I called her for the grand story behind The Future Library, which she shared with me with modesty. ‘I was daydreaming while drawing tree rings on a book when I saw the connection between the circles and chapters in a story: each filled with worlds that grow with time.’ The idea simmered for a while, but when the artist visited a festival in a Norwegian forest, it resurfaced. This time, she became so enthusiastic that she decided to stay in the forest for ten days to think it over. ‘I had no electricity or running water and was completely alone. Slowly, the idea for an artwork began to emerge: a forest that will grow for a century, with the voices of a hundred different authors.’

Beyond Time

At first, the project seemed impossible, but fortunately, many people were willing to help make it a reality. They formed a trust, and foresters helped find the perfect location. It had to be a place that was easy to reach but still felt far away. Grand, but intimate. It turned out to be a forest near Oslo. ‘We first cut down the trees that were already there. Then we planted the thousand spruces that are now growing.’ The artist then made a wish list of authors with the trust. ‘They are selected for their ability to look beyond time and generations, so of course, we asked Margaret Atwood.’ When she said ‘yes,’ everything fell into place: if Atwood participates, others will also help. David Mitchell, Sjón, and Elif Shafak followed. ‘It’s amazing that they are willing to create work for which they will never receive recognition during their lifetimes. It’s incredibly generous, and I can’t wait to see who will follow in their footsteps.’

The artist explains how the authors each resonate with the project in different ways. ‘Atwood’s stories travel far into the future and speculate on what the world will look like. Her participation feels like a brilliant first chapter of The Future Library. David Mitchell also makes leaps through time: light-years ahead, then reaching back thousands of miles through the present. It feels like a fascinating parallel to the project. Icelandic Sjón writes books, poems, and operas that are connected to time and mythology. His work fits so well with the project that it almost feels like a story he could have written himself. Elif Shafak’s work is magical. It often deals with contemporary issues and borders, but she has the power to look beyond them and connect people: from minority groups to huge nations.’ The rules for authors are strict: the book must be written in the original language, it can be of any genre, and its length can range from one word to a thousand pages. But no one may read it, and they cannot talk about it. The only thing they can share is the title. ‘It gives the authors a lot of freedom. They can write whatever they want, and no one from their generation will judge them.’

Writing on the Moon

The manuscripts are handed over during an annual ritual in the forest. The author arrives and walks with a group of people to the forest. There they drink coffee by a fire, and the title is revealed. Margaret Atwood’s book is called Scribbler Moon. ‘I have a great fascination with the moon, so I was delighted when I heard the title. It’s incredibly evocative, and I love to imagine what it might mean. Maybe it’s about writing on the moon, or writing about the moon. I have no idea, but with Atwood, I suspect it’s very activist.’

David Mitchell’s title comes from a Japanese composer and is called Through me Flows What You Call Time. ‘I imagine a story in a river of time, where you paddle across it and it can take you anywhere. Sjón’s title is so long and poetic that it’s almost a poem in itself. The English translation of his title is: VII: As My Brow Brushes on the Tunics of Angels or The Drop Tower, the Roller Coaster, the Whirling Cups and Other Instruments of Worship from the Post-Industrial Age. It could really be anything: from a few words to pages of poetry. Maybe it’s a song. Elif Shafak’s contribution is called The Last Taboo. The title suggests much and is laden with emotion. I imagine it will be a controversial and political work.’

The first two books of The Future Library are in English. Sjón’s book is in Icelandic, and it is unknown whether Elif Shafak wrote her work in English or Turkish, as she writes in both languages. ‘Diversity is an important part of the project. Of course, I want all the authors to have a genuine connection with the project, but I hope they express that in different ways: with their unique style and voice. My dream is that a hundred writers from around the world will participate, creating a rich variety of languages, styles, and sounds.’

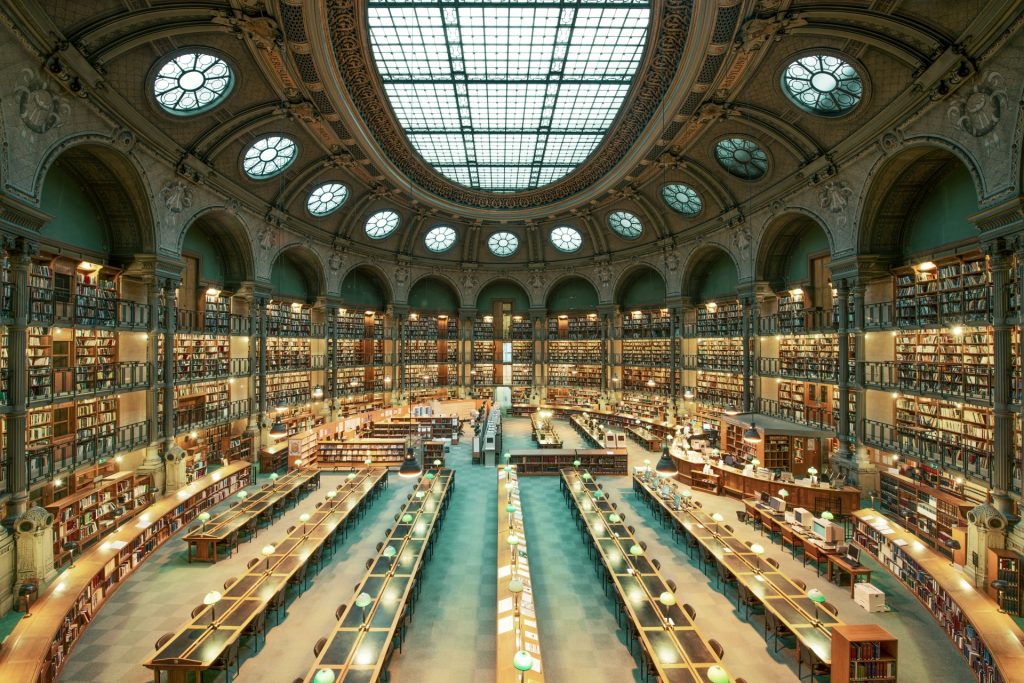

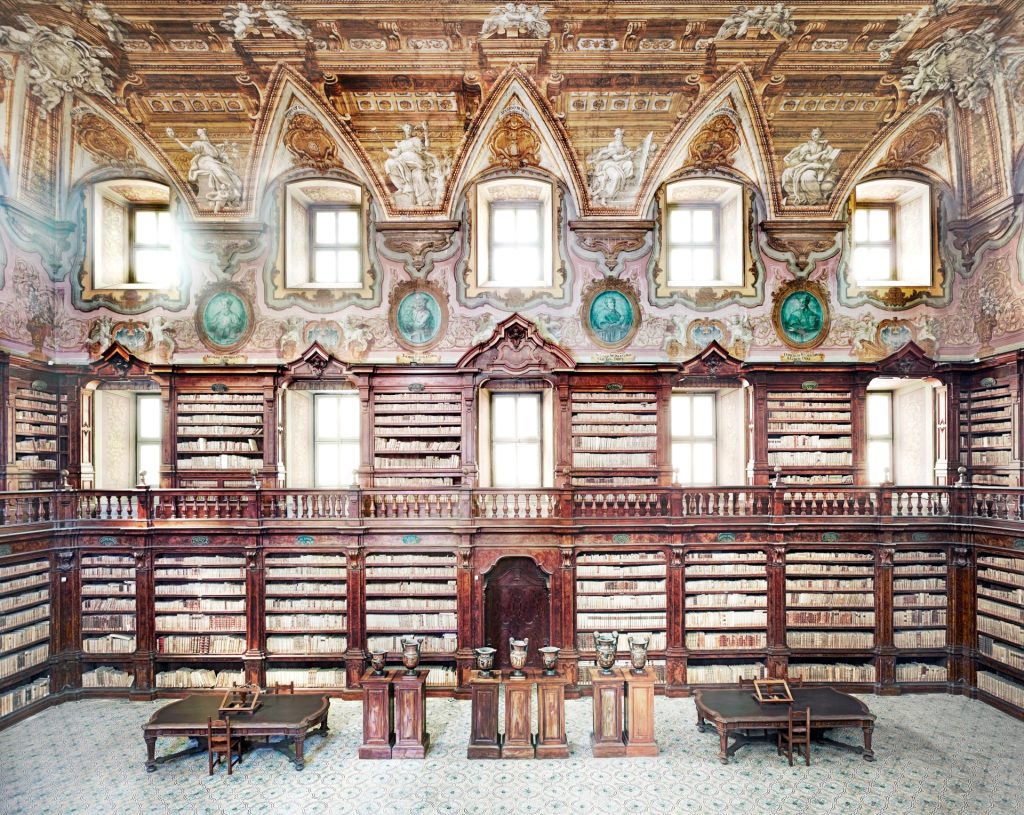

All the manuscripts will be stored in the new library in Oslo, which will open in 2020. ‘Together with an architect, I’m designing a room that will be built from the trees that were felled in the forest. It will be very minimalist. The books will be kept in drawers and will only have the author’s name, the year, and the title. Visitors can look at them and imagine what’s inside.’ The digital copy will go to the city archive and will be transferred over the years as technology changes.

A Beautiful Mystery

On August 31, the Future Library author for 2019 was announced: Han Kang. Paterson is delighted with her participation and is already looking forward to the annual ritual: ‘It’s such an incredibly special and emotional moment. I have a child who is almost one year old. He was there for the first time this year, and I like to imagine that he’ll be part of the generation that will be old enough to read the books. The library will grow with him. The trees are already thirty centimeters tall, and in twenty years, they will reach our shoulders. The most fundamental thing is that the project survives. We still have 96 years to go, and during the process, the world will change. People from the trust will pass away, and new people will join. I think a lot about the fact that I will also die during the project. That side of it feels confronting, but at the same time, its mystery is what makes it so beautiful. I have no idea who the people will be who will gather in the forest in 2114. Most of them haven’t even been born yet. I find that magical. We are making something for people who do not yet exist, but we think of them because they are the future.’ Paterson is aware of the uncertainties due to climate change and global issues, but she remains hopeful for the future and points to trees, stories, and imagination: ‘It’s incredible to think about everything that has changed in the last hundred years, but books are still here. They even still have the same form as they did a century ago! I want to believe that will endure. That we—humanity and nature—will endure, a giant leap forward.’