Amid a thousand messy wonders

Hans Arp

text: Annemiek Leclaire

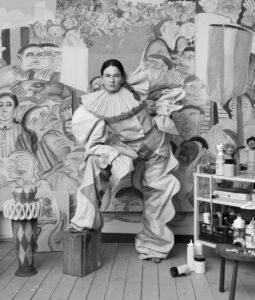

Hans Arp was a painter, illustrator, publicist and poet but became best known for his organic sculptures, which he preferred to give poetic titles such as Sculpture to lose in the woods. Together with his beloved Sophie, he belonged to the core of the European avant-garde.

It is 1909. 25-year-old Hans Arp has retired to a remote family cottage in Switzerland. The young artist wants to break away from his figurative way of working, but it is not easy. ‘It was an unbearable time,’ he will later write about it. ‘I lived lonely at the foot of the Rigi, between Weggis and Greppen. In winter I didn’t see a human being for months on end. I read, wrote poetry, drew, painted, carved little sculptures, and from the window of my small room I stared at the mountains covered in clouds of snow. It was an abstract landscape of uncompromising severity.

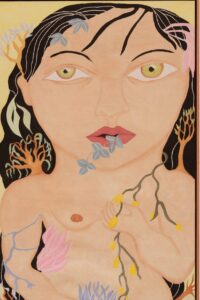

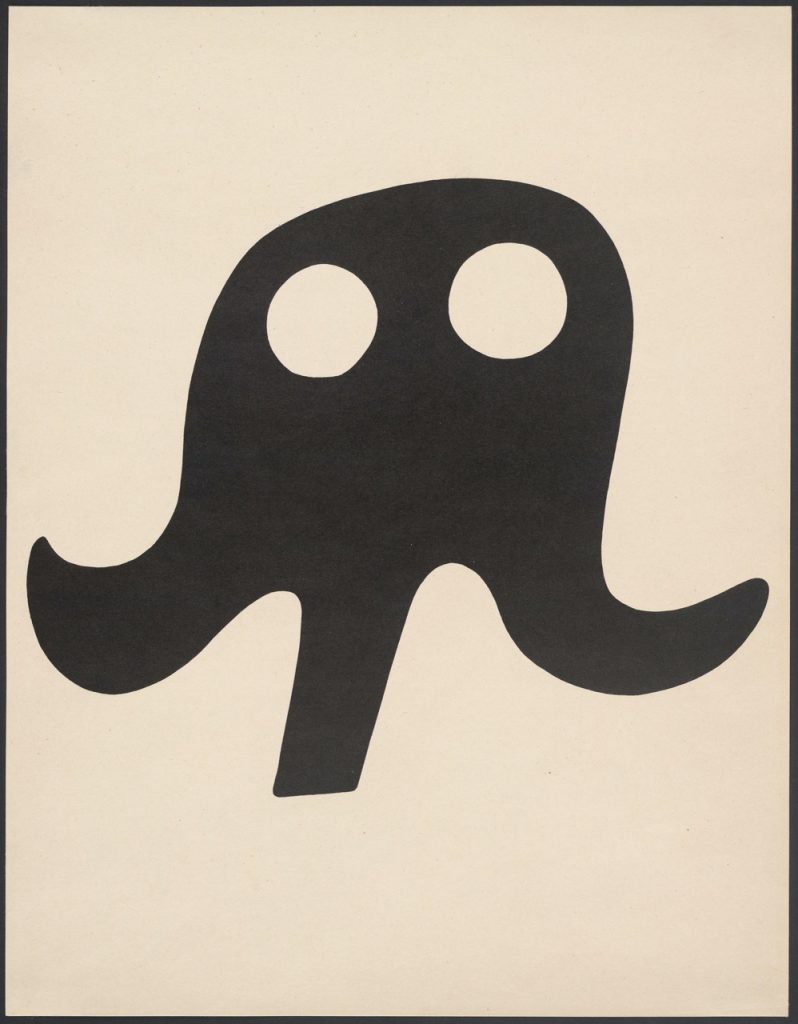

His struggle produces a series of monochromatic paintings in black, gray and white, which he discards afterwards. Nevertheless, he later calls that winter a decisive period in his artistry, because it succeeded in developing a personal style. Hans Arp (1886–1966) was born in the region of Alsace-Lorraine, which was still part of Germany at the time. In German, he calls himself ‘Hans,’ in French, ‘Jean.’ He was a poet, painter, and created collages, wooden reliefs, and sculptures. Arp’s visual language is referred to as ‘biomorphic’ or ‘organic abstraction’: these are mostly abstract, undulating forms that reference nature. Sculpture to lose yourself in the forest is a piece of work made of overlapping pebble-like forms.

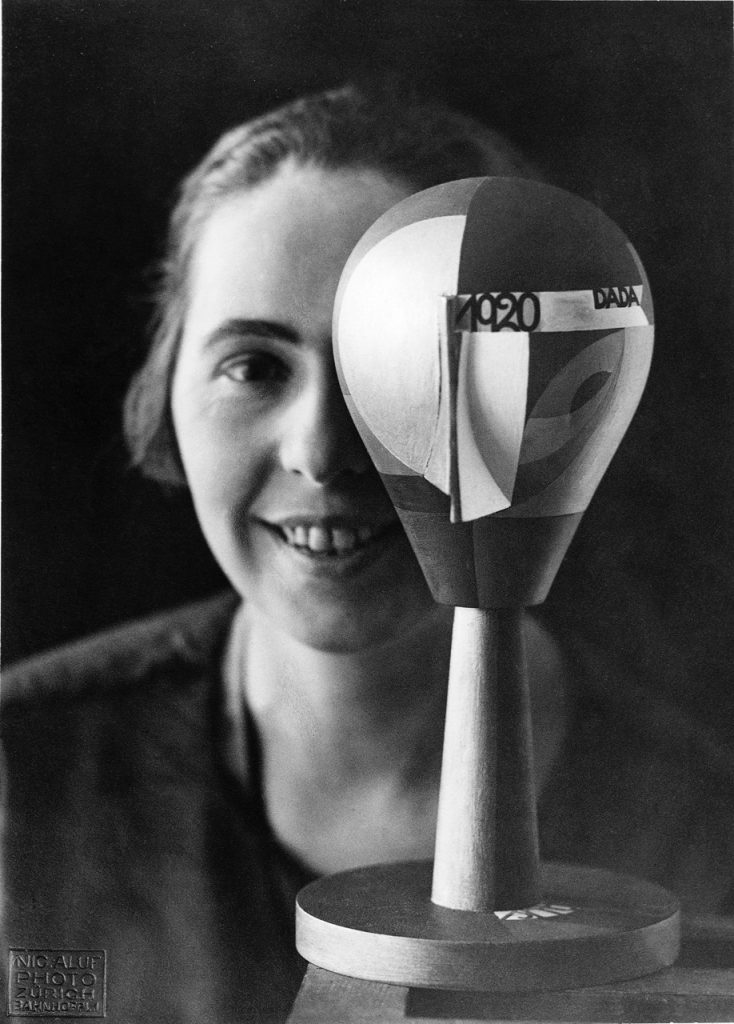

At the beginning of the twentieth century, Arp was not the only one working on the development of autonomous art. In Munich, he collaborated with the Russian-French expressionist Wassily Kandinsky and Paul Klee, who was inspired by primitive art. In Zurich, he and his fiancée, painter and dancer Sophie Taeuber, were among the co-founders of Dadaism, which, through collage art and nonsensical poetry, sought to ridicule conventional notions of art. Arp met Sophie during an exhibition in Zurich; it was love at first sight. ‘It was Sophie who, through the example of her clear work and her clear life, showed me the right path, the path of beauty,’ he wrote about it. They often worked together on collages and tapestries.

‘It was Sophie who showed me the way of beauty through the example of her bright life’

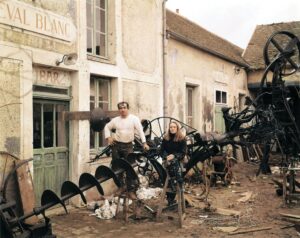

In 1923, he and Sophie moved into a studio in Montmartre, Paris, where they joined the surrealists. In the evenings, they met avant-garde artists like Joan Miró, Max Ernst, Salvador Dalí, and André Breton in the cafés of Place Blanche. In 1925, Arp exhibited alongside Giorgio de Chirico, Max Ernst, Paul Klee, Man Ray, and Joan Miró at the first surrealist exhibition in Paris. By then, he and Sophie had moved into their self-built house in Meudon, a suburb of Paris. They also hosted friends such as Piet Mondrian and Theo van Doesburg, the founder of De Stijl. The house is now a museum: La Fondation Arp.

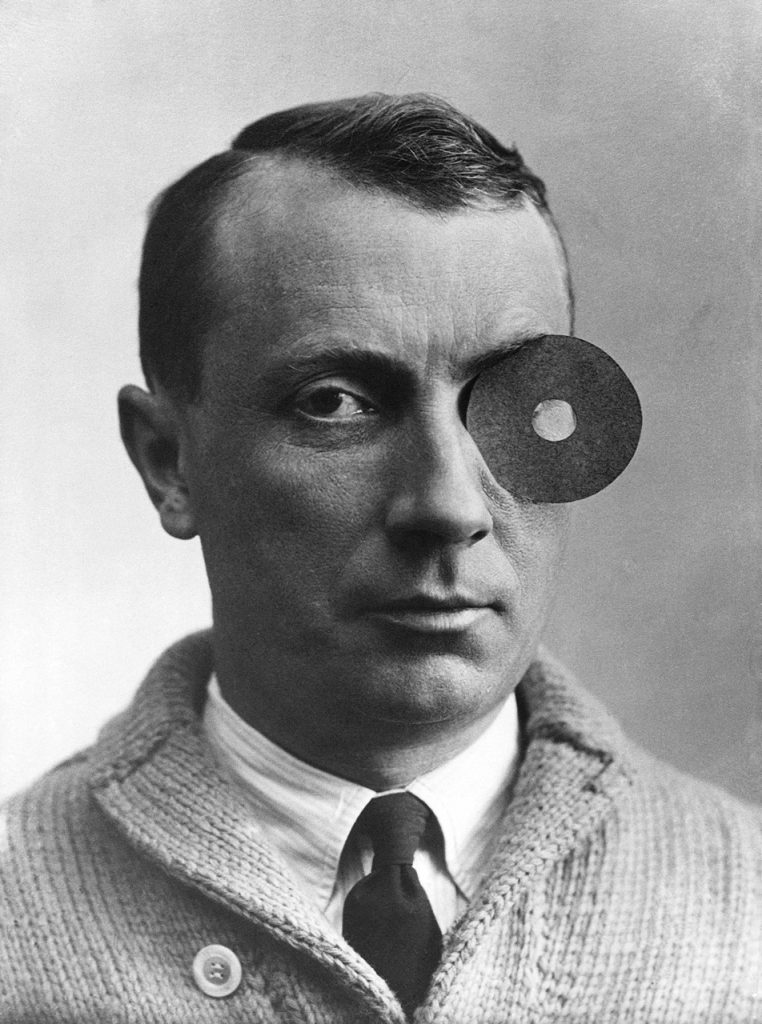

During these years, Arp explored chance as a driving force in art. He would drop pieces of paper randomly onto a sheet and glue them where they landed. Dreams, chance, and fantasy — what comes from chaos — played an important role in his work. This was based on the idea that what comes from the subconscious is ‘more natural’ than what humans devise. It is, after all, ‘reason’ that repeatedly leads to the horrors of war. How deeply Arp despised ‘reason’ is evident when, during World War I, he was detained by the German authorities in Switzerland and ordered to enlist in the army. When Arp had to fill in his details, he wrote his birthdate multiple times and added it up to create a nonsensical number. Arp was rejected on the grounds of insanity. ‘Behind his playful disregard for rationalism and patriotism lay a deep hostility toward the stupidity of the human race, and a sharp sense of the power of language, especially to tell lies,’ writes Eric Robertson in Arp: painter, poet, sculptor.

“At the end of 1942, Arp and Sophie fled to neutral Switzerland once again due to the war. Shortly after their arrival, Sophie died from carbon monoxide poisoning in the house where they were staying. Arp sank into a years-long depression, during which only poetry held his interest. The playfulness of juggling with clichés, as he had done in his Dada period, now eluded him. His poems became melancholic dreams of beauty and harmony in an empty life, in a war-torn Europe. Like Sophie dreamed Sophie painted Sophie danced (1944):

You dreamed of stars with wings,

of flowers that caress flowers / on the lips of the infinite,

of springs that unfold light,

of eggs that break symmetrically,

of breathing silken fabrics, / of serene sciences,

far from the houses with a thousand thorns,

with the kneeling of naïve deserts,

amidst a thousand careless wonders.

Critics find the poems uncharacteristically kitschy. ‘The fatally struck are not interested in issues of form,’ Arp himself writes about this. He is pulled back to life when he begins a relationship with Marguerite Hagenbach, an art collector and loyal friend of both Arp and Sophie. Hagenbach takes on the practical and financial responsibilities, allowing Arp to devote himself to art. These become the years of his greatest fame. The artist creates monumental sculptures for prestigious organizations, receives international awards, and holds retrospective exhibitions. But no matter what he creates, the heart of his work remains the timeless, undulating form language that gives his art its emotional power to this day.

In 1959, Hagenbach and Arp bought an estate in Locarno, Switzerland, and got married. There is a beautiful photo of the two on their wedding day: two happy older people having tea, sunbeams dancing on a table under the trees. When Arp passed away in 1966, he was buried in the grave of his first wife, Sophie. Since 1994, Hagenbach has also rested in this shared grave.