Ladies of the Night

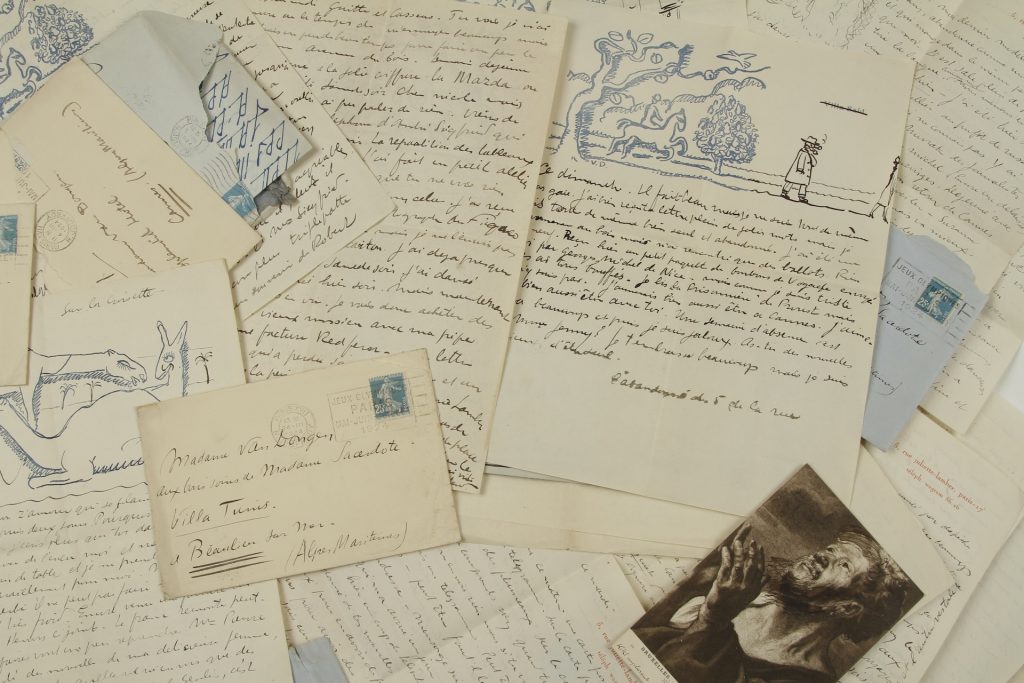

Profile of Kees van Dongen

Kees van Dongen, who was fascinated by women, is one of the 19th-century painters represented in the Van Gogh Museum’s exhibition Easy Virtue, devoted to the subject of prostitution in art from 1850 to 1900. Author Gustaaf Peek explores Van Dongen’s bold approach to these colourful women.

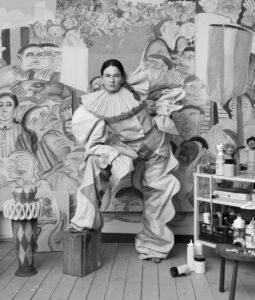

The first thing you might notice when you see archival photographs of the Dutch artist Kees van Dongen (1877-1968) are his strikingly bright, clear eyes. They seem to catch light, giving the artist an intense, piercing look. If these portraits had been in colour, Van Dongen’s eyes would have been lost in a variegated mass of hair shades and clothing hues. The fascinating, eternal attraction of black-and-white photos is that they emphasise the key elements and highlight the real pictorial world. No one recognises themselves in a good photo because no one is able to see in themselves what a photo reveals: the skin, the texture, the hair, the eyeballs, the cheekbones. In other words, the external appearance without the complications of the person within.

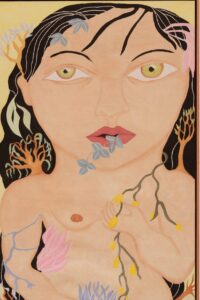

High-contrast black-and-white images of Van Dongen present a marked contrast to the artist’s work, which is extremely colourful. Van Dongen was one of the key Fauves and, like his fellow artists from that early 20th-century movement, he created paintings that explode off the canvas with the boldest possible pigments, chosen to achieve maximum effect.

In the 19th century, photography took over important functions from drawings and paintings. If you wanted to know what something looked like, you increasingly relied on photography. This was a godsend, in a certain sense, for painters. Photography released painting from the requirement to represent reality, and allowed it to enter new territories, with room for any and every notion or insight, dream or nightmare, in whatever form.

Colours convey meaning, operate at a primitive level and communicate primeval ideas about time and life. The primary colours, so central to the work of the Fauves, are the first colours that we humans are able to distinguish. Babies are able to differentiate between red, yellow and blue after three months. Only in the fourth month do infants develop the ability to perceive depth, which is one of the painterly elements that the Fauves deliberately omitted from their work. Van Dongen lived a long and productive life, remaining faithful to the Fauvist principles – and the technique of applying an expressive use of colour – throughout his long, successful career. This fidelity did not make his work monotonous; on the contrary, he created a wide range of works and explored the lines of his own talents to its various logical ends. He knew better than anyone who he was and what he was capable of. However, his varied approach to his work resulted in some misunderstandings.

During his lifetime, Van Dongen’s reputation changed over time. After the Salon d’Automne in Paris in 1905, he was regarded as one of the leading Fauves, but by 1968, when he died in Monaco, he had been demoted to a mere ‘society painter’. This seems like the tragic end to a bad film: a talented man fights his way to the top, rising far above his modest but meaningful beginnings only to end his life in decadence and bitterness. But studying his life, one gets a strong impression that he was surprisingly aware of his own talents and ambitions, of the advantages of fame and the scope of an artist’s life.

Something ‘Different’

Van Dongen doesn’t fit the cliché of the tormented, socially alienated artist. His early paintings of prostitutes and half-nude female dancers aren’t a document a bohemian existence he lived among the rough social classes. Rather, they are an expression of his lifelong exploration of the essence of Woman. Prostitutes and dancers just happened to be the kind of women he was surrounded by at that point.

Later, once his work received the popularity it deserved, Van Dongen moved to ever larger and more richly furnished studios, which he also used for parties, networking and receiving collectors. All that champagne and dancing did not make him any less of an artist; it simply changed his subject matter. Suddenly the women in his circles were wearing expensive clothes and sporting stylish haircuts, but he continued to explore their posture and mannerisms with the same intense scrutiny as before. As an artist, Van Dongen has always remained straightforward,engrossed by his subjects and obsessed with the effects wrought in the paint.

The Role of Extra

Art history has its favourites. The grand twosome Picasso and Matisse seem to relegate other exceptional artists around them, like Van Dongen, to the role of extras in the large narrative of art history. But this limited canonisation is an opaque, unjust process. Both Matisse and Picasso died wealthy in self-glorifying conditions, but they were not saddled with accusations of unbridled ambition and greed as Van Dongen was. Eventually, enough years will pass to obliterate memories and leave only a few artworks, and who knows where the extras will end up in the hierarchy then.

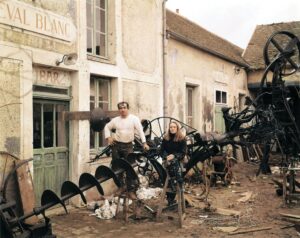

There is a photograph of Van Dongen in his fifties, apparently carefully studying a woman who is wrapped in towels, undergoing a beauty treatment. The artist’s hair and beard are both completely white, and he seems respectably dressed. His stance appears to be a pose but he also seems slightly amused. This photo fits perfectly with the image I have of Van Dongen in my mind: a generous man with an inquiring mind whose self-confidence was not affected by superficial matters.

I discovered somewhere in my research that Van Dongen earned money during those tough initial years in Paris ‘by selling newspapers and performing as a wrestler’. Why shouldn’t someone from Delfshaven in Rotterdam, who grew up in his father’s malt-houses travel to Paris to become an artist? Why shouldn’t someone who wrestled to make ends meet go on to parade Monaco’s boulevards? I am always amazed by the power of the imagination in artists, the huge chasm they are able to bridge between what is and what they envision, with such assurance.

Van Dongen was a hard worker who also knew how to enjoy life, an entrepreneur and avid traveller, a good host, a good dancer and tireless networker. He is the artist who captured a variety of different women with a kind cheerful obsessiveness. Each woman, whether prostitute, wife, actress or grande dame, is accorded the same attention and the same inquisitive, firmly caressing gaze.

What’s clear is that Van Dongen must have been endlessly fascinated by women. In Seated Woman from 1911, a young girl reclines with one leg tucked behind her on a floral sofa. She has a pensive look on her face, and she rests her arms on two richly decorated cushions. Her left breast is exposed, but it is striking how unobtrusive and casual an element this is in such a riveting, captivating work.

On the subject of painting women, it is a pity that Van Dongen once said: ‘The essential rule is to paint them to look a bit taller and thinner. Next you have to make their jewellery appear slightly larger. Then they’re always satisfied.’ These hardly seem like the words of someone who worked year in year out on turning his female models into intriguing myths, who as a boy studied and drew the prostitutes of Rotterdam and at the end of his long life exaggerated the jewellery in his paintings. But why shouldn’t he?