I am the one who devours

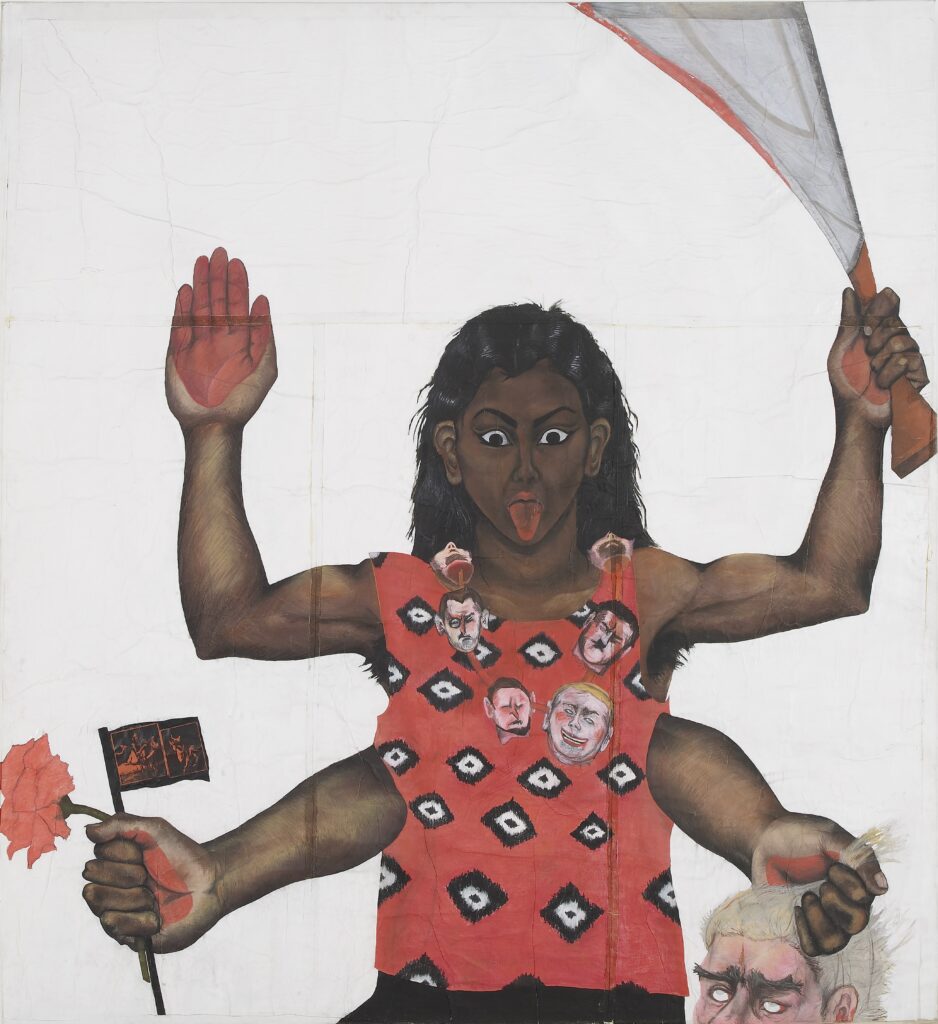

Goddess Kali

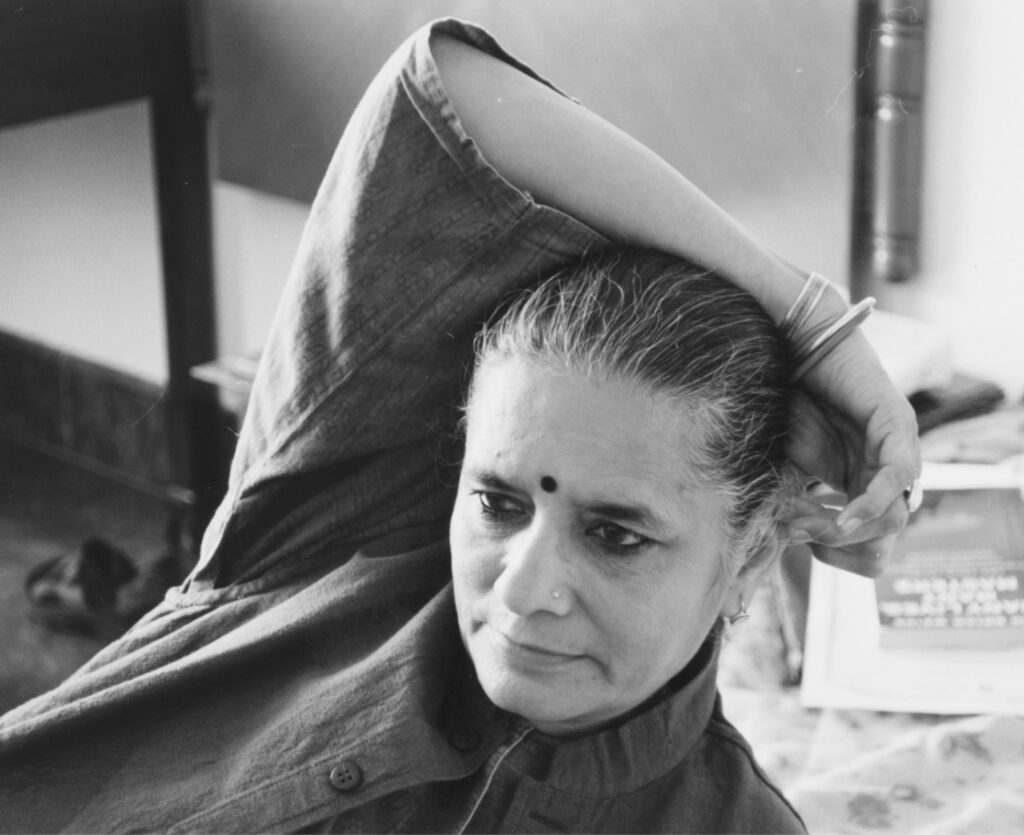

Leading the way through See All This #38 are six divine figures – goddesses from various eras and cultures. Artist Sutapa Biswas, grew up surrounded by images of goddesses. ‘There is one in particular with eight arms, riding a tiger which I hung above my bed. She was my muse,’ she tells about Hindu Goddess Kali: goddess of creation and destruction, time and change.

‘Ever-blissful Kali,

Bewitcher of the Destructive Lord,

Mother –

for Your own amusement

You dance,

clapping Your hands.

You with the moon on Your forehead,

really You are primordial, eternal, void.

When there was no world, Mother, where did You get that garland of skulls?

You alone are the operator,

we Your instruments, moving as You direct.

Where You place us, we stand; the words You give us, we speak.

Restless Kamalakanta says, rebukingly:

You grabbed Your sword, All-Destroyer,

and now You’ve cut down evil and good.’

— Kamalakanta Bhattacharya, from: Rachel Fell McDermott, Singing to the Goddess,

Poems to Kali and Uma from Bengal, Oxford University Press, 2001

Since its creation between 1983 and 1985, my painting Housewives with Steak-knives has occupied a life of its own, becoming an iconic and recognisable work of the late 20th century. It began life in my studio during my undergraduate studentship at the University of Leeds. My hands moved the soft Rembrandt pastels across a narrow strip of utilitarian paper to mark the presence of the brown face of a woman who resembled myself. It was as if the articulation came both from my body and some external force. Her tongue gesturing outwards, she looked back at me as if to command that I cut more strips of paper and add these to either side of her head, thus making space to bring her body to life. I worked on the flat of her torso adorning the tabard she wears with the Ikat pattern borrowed from a tunic I had purchased locally from a fashion house and frequently wore. ‘Kali’ projecting herself outwards and back towards me like the canvas sail of a boat caught in wind’s speed. Her arms grew wider occupying with certainty the large space of the papery folds behind her, from which she emerged.

Almost a year after completing this painting, and nearly twenty years after arriving in England, I made my first return journey to India, my birthplace. Among my first visits was the former home of my adoptive paternal grandmother (Didima), with whom I had been close as a young child but who had passed away years before my return. Didima had been widowed only days after her marriage. Unknown to me at the time of making Housewives with Steak-knives, she was renowned in her district as a strong devotee of the goddess Kali and a prototype feminist. Even more remarkable was that she had left me a small print in her will – one she had kept on her mantelpiece depicting the goddess Kali. The pattern on Kali’s clothing in this print exactly matched the Ikat design of the tunic I had purchased, which I had incorporated onto the body of my painting Housewives.

On my return to England, I asked my mother why, when she had first encountered this painting in an exhibition at the ICA in London, she had not mentioned these connections to me. She replied that she assumed I must have known. I didn’t. It was around this time that I began to consider the spiritual, ghosts, and the unconscious. Searching for the beginnings of my connection with goddesses and spirits, remembered as if seen through the eye of a bird, my mind travels across geographies unravelling words –like threads pulling loose from the embroidered details at the edges of my mother’s clothes.

‘My hands moved the soft Rembrandt pastels across the paper to mark the presence of the brown face of a woman who resembled myself’

The etymology of my given name ‘Sutapa’ functions as both noun and a verb. My father told me that in Sanskrit, it’s associated with the spirit goddess of wisdom. Existing in both masculine and feminine forms, it represents a spirit belonging to the underworld. My family’s pet name for me derives from the Sanskrit word ‘bhootas’ – a spiritual being who has the power to exist in liminal space between worlds. In classical Sanskrit in Tantric traditions, ‘bhootas’ are powerful, enigmatic entities known for revealing hidden knowledge. Often considered a lower realm spirit (ghost), the Karna Pishachini specifically is associated with the ear (karna) and is said to whisper arcane wisdom directly into the practitioner’s ear.

Each child, it seems to me, possesses a spiritual dimension – an inner quiet gift to commune with dimensions beyond the immediate scope of being quantifiable via accepted traditions. We marvel at their imaginings, which sometimes feel almost magical. Yet in Western, Eurocentric contexts, a child’s ability to think abstractly, is something that, around age five, our capitalist cultures begin to ‘school’ out of them.

I was born in Shantiniketan, India in 1962 while my father, an agronomist, ecologist, and academic, taught at the university. It was part of a complex of educational institutions founded on the philosophy that the arts, theatre, literature, philosophy, science and maths physics, should sit together, allowing the mind to study and flow seamlessly between disciplines. A place where the physics and mathematics of cosmos co-existed on stage, in a dance with the mundane.

Though my family left when I was still an infant, leaving me with few memories of this extraordinary place, I recall my father chanting his mantra ‘dance, music and play’ as being the very essence of life. It became a compass for me as I developed deep connections with nature, trees, and the animal world. Connections sealed through witnessing the hypnotic concentration of women as they painted rangoli on brown earth with flour and coloured spices during the many festivals (pujas) each year. A time when children played with abandon, ate sweetmeats while perched in trees, surrounded by the musical din of drums and chanted prayers. All this unfolded in open spaces that seemd to transcend the mortal world, where even fireflies drew one’s gaze toward the night sky and beyond.

‘I recall my father chanting his mantra “dance, music and play” as being the very essence of life’

Like most children, I made art from a very early age. However, it was perhaps my first encounter with classic Indian films in a London cinema that truly sparked my understanding of the connection between art and life. On screen, dark-skinned characters with black hair spoke my parents’ language, their images projected across the cavernous theater. Aware of the concentration of my parents’ faces, though too young to follow the plot, my attention was intermittently drawn towards the specks of dust momentarily suspended in beams of projected light. I couldn’t articulate it then, but this framed triangulation – the cosmic dance created by light, film and my parents – continued to hold me.

The worlds of goddesses and ghosts continued to inhabit my life through female divinities displayed in makeshift shrines throughout our home – in my mother’s room, on mantel pieces, and on kitchen calendars. Above my bed hung an image from an old calendar depicting a goddess with eight arms carrying an assortment of objects: a dahlia flower, a bow, a spinning chakra, a sword, and a conch shell. Dressed in an embroidered red sari with a distinctive halo illuminating her black curly locks, she confidently moving across the moonlit landscape. We communed often, as children do with pictures in books. Perhaps unsurprisingly, my early paintings from about age eleven depicted mysterious adult female figures caught in a process of transformation, emerging from the tree bark in moonlight. In my mind’s eye, they were goddesses and creatures from a matriarchal world that inhabited my imaginary.

‘The experience was a rude awakening’

During my first undergraduate year at the University of Leeds – studying Fine Art, Art History, and History and Philosophy Science — a white female visiting lecturer who identified as feminist made disparaging remarks about my artwork without understanding my upbringing or the matriarchal cultural references of goddesses that had shaped me. The works portrayed the female body morphing between different forms of figuration, which she dismissed as merely complying with stereotypically oppressive representations of women in the mainstream dominant culture – without acknowledging that she was referring specifically to the Western canon. Hierarchically implicit in her remarks was a notion that the Western canon was what was significant. When I mentioned artist Leonor Fini as an example that surely transcended these stereotypes, the tutor asserted that Fini possessed the knowledge, skills and intellect to subvert such dominant representations of women and that I was incapable of achieving this. The experience was a rude awakening. Rather than embodying feminist ideology’s commitment to equal exchange and willingness to learn from voices outside Eurocentric narratives, her approach was undermining and dismissive.

This encounter didn’t sit in isolation within the Fine Art and Art History course. Despite claims of being rooted in radical Marxist, feminist, and post-structuralist approaches, the curriculum remained very Eurocentric. It was in this context that my painting Housewives with Steak-knives was born – created in resistance, anger, and defiance, in communion with all the spirits and deities who are simultaneously ordinary women and ‘goddesses’ that captured my imagination and with whom I have since communed.

Artists featured in this chapter:

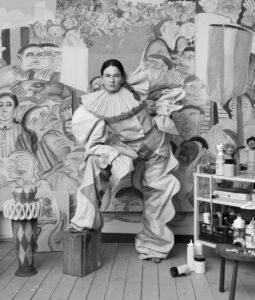

Sutapa Biswas

‘The iconographic images of ancient goddesses I have drawn on are images of goddesses I grew up with, which were displayed in our home… There is one particular image of a goddess with eight arms, riding a tiger, which I hung above my bed. She was my muse.’

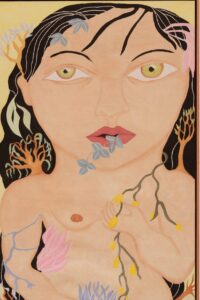

Samira Abbassy

‘Everyone is born on a fault line, if only they knew it. After reading Salman Rushdie’s Imaginary Homelands, I realised once you’ve left a place it becomes a kind of Never Never Land. So I became a “fictional historian”, reinterpreting stories about a place I barely knew.’

Jongsuk Yoon

‘I believe that painting is a medium that is able to demonstrate the authenticity and symbolism of art as a powerful tool of change.’

Samah Shihadi

‘I want to chase anything that gets in my way’

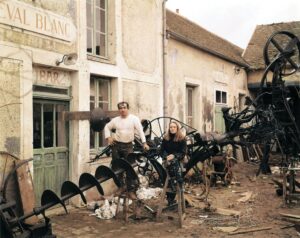

Madhvi Parekh

‘On my way back from school, the setting sun would set the whole world around on fire and bathe it in shimmering golden light. Those colours have become an integral part of me and they come to me quite naturally. ’

Arpita Singh

‘The affairs of political and social life come into my painting like the way light comes as colour and breeze comes as movement.’

Aysen Kaptanoğlu

‘I explore violence, its origins and the structures that reproduce it. Using memory and self-experience as means of assistance, I am trying to make sense of what doesn’t make sense.’