The urinal is not by Duchamp

Duchamps brutal act

Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain was declared “the most influential modern artwork ever” in 2004. The porcelain urinal is considered more significant than Picasso’s Guernica. But is Duchamp really the creator of this iconic piece? No: Fountain was made by Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, the very first artist to turn found objects—objets trouvés—into art. It’s high time we rewrite history and give this founding mother of modern art the recognition she deserves.

When {{Fountain}} suddenly appears in April 1917, it splits the New York art scene in two. In Europe, a world war has been raging for three years; the United States has so far remained on the sidelines, and New York is pulsing with optimism. It’s the era of New York Dada, a movement launched in 1915 by artists like Marcel Duchamp, Francis Picabia, and Man Ray. In 1916, the Society of Independent Artists is founded, inspired by French models, with the goal of organizing exhibitions for avant-garde artists. Duchamp joins the board.

From April 10 to May 6, 1917, the society hosts its first exhibition. Anyone who pays six dollars may exhibit. But it’s not the more than two thousand works, arranged alphabetically, that stir things up. One particular submission causes Duchamp to resign from the board and sends shockwaves through the New York art world: a porcelain urinal.

During the short time the piece is present at the exhibition, it leads a rather inglorious existence, hidden behind a shabby curtain. No visitor to the show ever sees it. The urinal bears the cryptic signature “R. Mutt.” The combination of banality and mystery proves too much for most organizers. The piece is rejected. Outraged by this decision, Duchamp steps down from the board.

Alfred Stieglitz photographs the urinal in his studio—this is the only image of the original. What happens to the piece afterward is shrouded in mystery. Some say it was smashed, either by accident or in the heat of an argument among board members. Others claim it was thrown out immediately and unceremoniously. There are stories of a furious Duchamp lugging it home, hanging it in his studio for a while, then discarding it. Duchamp’s biographer, Calvin Tomkins, suspects Stieglitz simply put it out with the trash after taking the photo.

But who, really, is the mysterious R. Mutt—the person who submitted the urinal?

Buddha of the Bathroom

Attached to the urinal is a label bearing the name “Richard Mutt,” written in a different handwriting than the signature on the porcelain itself. The address on the label is only partially legible, but it points to the temporary residence of Louise Norton, an artist and friend of Duchamp. The press soon discovers that the urinal was sent from Philadelphia, but finds no trace of a Richard Mutt.

The sender didn’t give the artwork a title. That came about by chance. In a review of the exhibition published on April 10 in the New York Herald, critic Gustav Kobbé refers to the urinal as a fountain. In keeping with the moral codes of the American media at the time, it was highly inappropriate to use the word “urinal” in print. Kobbé’s euphemism caught on. In the May issue of The Blind Man—the little magazine of the New York Dada scene, which also printed Stieglitz’s photo—the urinal is again referred to as a fountain: “They say any artist who pays six dollars may exhibit. Mr. Richard Mutt sent in a fountain. This object disappeared without discussion and was never shown.”

The fiery article was written by Louise Norton, whose temporary address was partially visible on the urinal’s label. In her piece, “Buddha of the Bathroom,” she writes: “Is it Mr. Mutt’s art, since a plumber made it? I simply answer that Fountain was not made by a plumber but by the force of imagination.” The foundational principles of conceptual art are stated above her article: “Whether Mr. Mutt made the fountain with his own hands or not has no importance. He CHOSE it.” Yet even here, Norton doesn’t reveal the identity of the person who made the artistic choice. Duchamp, too, remains silent. So who was it that chose to elevate the urinal to the status of art?

When André Breton publishes his article “La Phare de la mariée” in the surrealist journal Minotaure in 1935, Fountain is, for the first time, attributed to an artist. Breton names Duchamp as its creator.² On what basis, no one knows. “The article appears to be based on extensive conversations with the artist,” is the cautious verdict of Tate Modern, which holds a Duchamp-authorized replica in its collection.³ After Breton’s article, Richard Mutt vanishes from history and is never seen again.

Right?

What Duchamp himself would later say about the origins of Fountain hardly clarifies anything. Over the years, he circulated multiple versions of the story. Fifty years after the fact, in 1967, he confided in the painter Enrico Baj a tale about a party at the apartment of Walter Arensberg, the wealthy New York art collector and patron of Duchamp. A drunken guest, searching for a bathroom, climbed a staircase. “Partly because of the pressure on his bladder and partly out of mischief, he peed from the top of the stairs. A little stream trickled down, step by step, finding its way to the front door and the gathered guests.” Duchamp claimed he bought the urinal to satisfy Arensberg’s sudden need to install more sanitary facilities in the apartment.⁴

In an earlier account, which Duchamp put forward in 1964, he told how Joseph Stella, Walter Arensberg, and he walked in April 1917 to J.L. Mott Iron Works, a plumbing supply store at 118 Fifth Avenue in New York. There, Duchamp purchased a urinal, brought it back to his studio, laid it on its back, and signed it. “Mutt,” he claimed, was simply a nod to “Mott.”

In the 1960s, William Camfield, who became friends with Duchamp, wrote a book about Fountain, in which he called its origin “an intriguing mystery.”⁵ In a 2017 interview marking the centenary of Fountain, Camfield was asked if he had often discussed art with Duchamp. “Yes,” he replied, “but he didn’t like to talk about his work. For example, I never asked him anything about Fountain.”⁶

When the interviewer pressed him: “There’s some disagreement about whether Duchamp actually made the thing. It was him, right?” Camfield’s answer was brief: “For me, there’s no disagreement.” “So there’s no doubt?” “No doubt,” Camfield replied, curtly.

How Camfield came to that conclusion—despite admitting he didn’t know how the work came into being and had never spoken to Duchamp about it—remains unexplored. The origin of Fountain is a riddle, wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma. And it begins with the object itself.

One of My Lady Friends

“Although several replicas of Duchamp’s Fountain exist, it has proven impossible to find a surviving original of this type of urinal,” reflected Kirk Varnedoe of the Museum of Modern Art in 1990. “If it does exist, it is now an object of extraordinary rarity.” British art historian Glyn Thompson believes he found such a specimen in St. Louis after much searching. It was made by the Trenton Potteries Company of New Jersey, Thompson writes.⁷ But this model was not sold by J.L. Mott Iron Works in 1917. The company only sold what it manufactured itself. Moreover, Thompson discovered that the New York address in question was not a store, but merely a showroom. “This undermines Duchamp’s claim that he purchased the urinal at J.L. Mott Iron Works.” Another reason Duchamp couldn’t be the creator of Fountain, according to Thompson: Duchamp lived in New York, and the urinal was shipped from Philadelphia. His conclusion: Duchamp did not make Fountain.

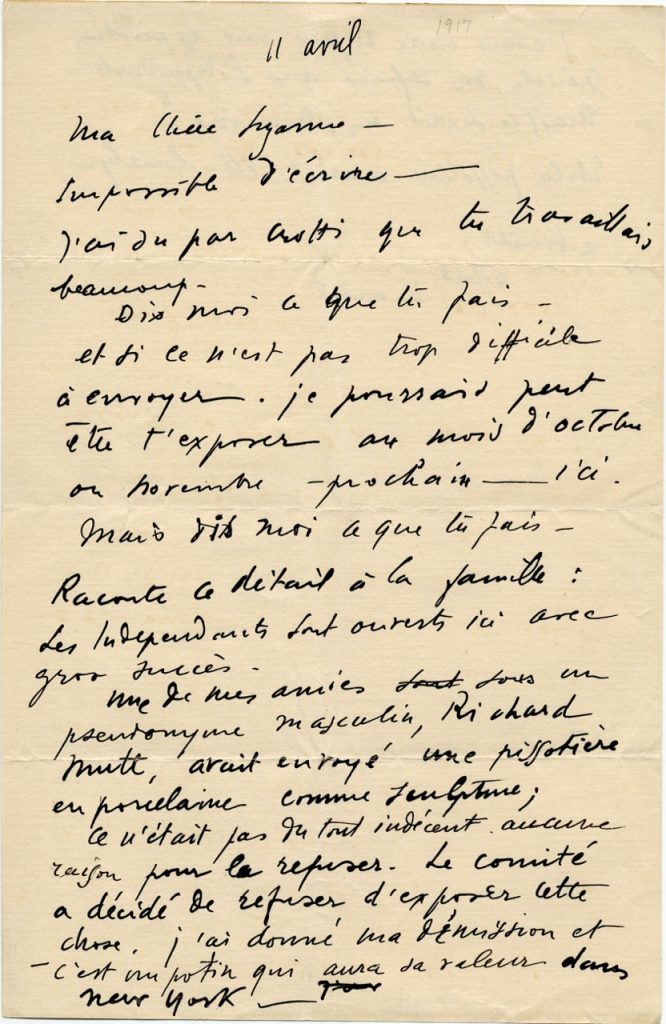

In 1982, a sensational article appeared containing ten newly discovered letters written by Duchamp to his sister Suzanne and her husband.⁸ “Marcel Duchamp didn’t like writing letters,” Francis M. Naumann notes in the foreword. “He claimed writing bored him to death and only wrote to his correspondents when he felt it necessary.”⁹ In other words, when Duchamp did write, it wasn’t idle chatter—Naumann seems to suggest it meant something. In one of these letters, Duchamp offers a surprisingly candid glimpse into the genesis of the most talked-about artwork of the twentieth century.

On April 11, 1917, shortly after the urinal caused a stir, Duchamp wrote a letter to his sister, who at the time was working as a nurse in war-ravaged Paris. One passage is stunningly revealing: “One of my lady friends, using a male pseudonym, Richard Mutt, sent in a porcelain urinal as a sculpture; it was not at all indecent—no reason to reject it. The committee decided to refuse it for the exhibition.” With this, Duchamp admits that it wasn’t he, but someone else who submitted the revolutionary work of art. A woman.

But who?

Loves Dada, Lives Dada

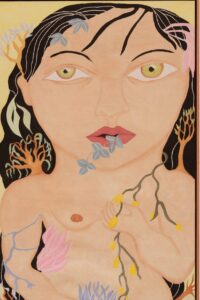

“She showed up at his studio and volunteered to model. She flung open her red raincoat to expose herself. Over her nipples she wore tin tomato cans, held in place by a green cord around her neck. Hanging between them was a tiny birdcage with a canary inside. One arm was adorned with curtain rings she had stolen from a department store. She had taken off her hat, which she had decorated with gilded carrots and other vegetables.” This is how artist George Biddle, in his 1939 memoirs, describes the American Dada artist Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven.¹⁰

Margaret Anderson, founder and editor of the literary New York magazine The Little Review, remembered her like this: “On her chest dangled two tea infusers with the nickel worn off. On her head she wore a cap with a feather and sorbet spoons… When one of the editors told her that her submitted poem was ‘wonderful,’ she replied, ‘Yes, it is.’ She called The Little Review ‘the only magazine about art that is itself art,’ and then promptly walked away. On her way out, she snatched a sheet of postage stamps.”¹¹

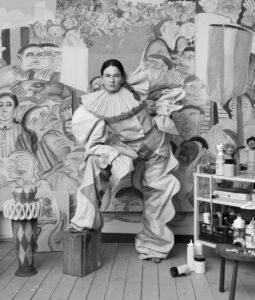

From 1918 to 1923, Elsa’s striking figure was often seen on the streets of Greenwich Village. The German-born artist even lived in the same building as Duchamp for a time. They spoke frequently. “Today, Elsa would be recognized as the iconoclastic, radically innovative and rebellious artist that she was,” explains Elsa’s biographer, Professor Irene Gammel. “She was a disruptive force, even within the Dada group. As Jane Heap, editor of The Little Review, said: the Baroness is the only person in the world who dresses Dada, loves Dada, lives Dada.”

Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven’s life was one of transformation, gender-bending, activist body art, and breaking conventions. That started shortly after her arrival in America, when she was arrested on the street for wearing men’s clothes. “I wore men’s clothing because I could move more freely in it, because I felt better in it, because there was no weight dragging me down, because I could travel anywhere without being harassed, because I believe a woman has the right to dress however she wants,” Elsa told the astonished police officers at the station on Sixth Street and Penn Avenue in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.¹²

It was September 1910, and Elsa—then still Elise Greve—had just arrived in America. Her husband cut her hair short. The suit she set out in cost barely $9. A police officer noticed by her shoes that she was a woman, and she was arrested. “We women pay heavy fines simply for our sex,” she told Gertrude Gordon of the Pittsburgh Press, with a smile “framed by a touch of cynicism.” Elise Greve was ahead of her time. It would be another ten years before Duchamp dared his own androgynous leap with his alter ego, Rrose Sélavy.

She *Is* the Future

In 1913, Elise married a German baron and became Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven. Everyone who knew her called her “the Baroness.” On the way to her wedding, she found an iron ring on the street and picked it up. For her, it wasn’t just a discarded object—it symbolized Venus, her femininity, which she had hidden in Pittsburgh beneath a mantle of supposed masculinity. She gave the object a name: Enduring Ornament.

“Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven deserves credit for declaring found objects or objets trouvés as art as early as 1913, before Duchamp had even arrived in New York,” Gammel clarifies. “She also pioneered assemblage art, creating sculptures from trash she found on the street.” Abstract artist Lorser Feitelson (1898–1978) remembers: “Freytag-Loringhoven came by with a bundle of pipes she’d picked up on the corner, dragging them up the stairs. It sounded like someone was tearing the building apart. She said, ‘Isn’t this a great sculpture?’ And she wasn’t joking.”¹³

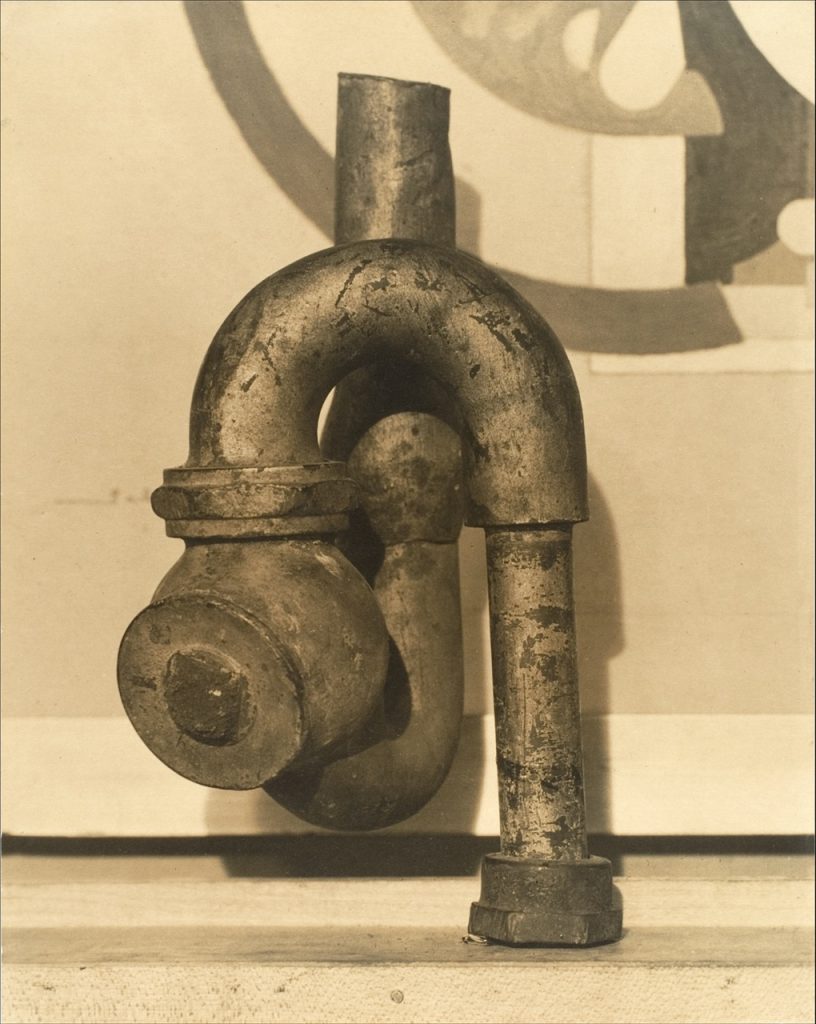

This is also how her remarkable 1917 sculpture God came about—a swan-neck pipe she had found. Only recently has it been established that God was the work of Elsa, not modernist painter and photographer Morton Schamberg.¹⁴ Created in the same year as Fountain and now attributed to Elsa, God is even seen as a sister piece to Fountain.¹⁵

In 2002, Gammel finally made the connection between Elsa and Fountain in her biography. In his book on Fountain, Camfield dismissed the information in Duchamp’s letter as a little lie. He speculated that the mysterious “lady friend” may not have come up with the idea, but simply shipped the urinal: “Did she live in Philadelphia,” he wrote, “because newspaper reports kept identifying Mutt as someone from Philadelphia? But no contact from Philadelphia has yet been identified.”¹⁶

“That’s not true,” says Gammel. She points out that Elsa was in Philadelphia at the time and concludes about Fountain: “There is a wealth of circumstantial evidence pointing to her artistic fingerprint.”¹⁷ She still stands by that. Elsa, about whom Duchamp himself said: “The Baroness is no Futurist. She is the future.”

House of Cards

Art critic, former museum director, and curator Julian Spalding is even more emphatic: “I’m convinced that Elsa is the creator. Duchamp had nothing to do with making or submitting the urinal, but later claimed it as his own. He didn’t just steal it, he stripped it of its meaning. Elsa’s urinal didn’t say that any found object becomes art if an artist says so (a false premise that became the foundation of conceptual art). It was in fact a remarkably penetrating and beautiful sculpture—the first physical (in this case, porcelain) poem, and the first great feminist artwork, deserving a place beside Man Ray’s Gift and Picasso’s Bull’s Head as one of the iconic images of the twentieth century. Worse, Duchamp buried the reputation of one of the true geniuses of early modern art—a female artist at that! The history of modern art must be rewritten.”

According to Spalding, there is ample evidence to credit Elsa as the author of Fountain. “The urinal fits completely within Elsa’s body of work, alongside her sculpture God, also from 1917. It works perfectly as an attack on America, which she saw as a men’s club (symbolized by a men’s toilet), and which had declared war on her motherland, Germany. Hence the wordplay in the signature: R. Mutt.” If you move the ‘R’ to the end of ‘Mutt’ and pronounce it phonetically, it sounds like Mutter, the German word for “mother.” Thompson also notes that R. Mutt wasn’t a real person but a pun—something Elsa often created in both English and German. Phonetically, R. Mutt can be heard as Armut, German for “poverty.” Gammel discusses other variants as well, including Urmutter, “primordial mother.”¹⁸

What pushed Spalding over the edge was Thompson’s discovery that J.L. Mott was not a store but a showroom: “The story Duchamp told about buying the urinal there had to be a lie. That, combined with the letter to his sister and the crucial fact that Duchamp had by then given up making art—he had turned to pun-making after Raymond Roussel—brought the whole house of cards crashing down.”

Why doesn’t this spark a louder debate in the art world? Spalding: “The art world refuses to consider it. It undermines everything the art world has promoted over the last forty years, and the art in which it has invested.”

Why did Duchamp steal the iconic work from Elsa? That remains speculation, says Spalding, but he has an idea:

“Duchamp was 73 in 1960 and felt death approaching. He wanted to go down in history as one of the founding fathers of modern art alongside Picasso, Matisse, Kandinsky and Mondrian. He had nothing astonishingly original from that period to show, so he claimed the urinal. In doing so, he erased the reputation of the primal mother of modern art.”

Why is Elsa still not recognized as the creator of Fountain?

Money and the existing power structures in the art world are to blame, says Thompson: “The establishment, the agencies that control what can be believed and published about Duchamp, fiercely protect their self-interest. Anything that threatens the dogma’s hegemony is excluded. Too much has been invested in the prevailing myth. The art world ignores what it does not want to know and ensures dissenting voices are never heard.”

Academics risk their careers by emphasizing this story, says Thompson.

Living in Poverty

Elsa lives in poverty in America—*Armut* in German, sounding like “R. Mutt.” She lives in shabby apartments or sleeps on the streets. She earns income by stealing or posing as a model. Despite her brilliant poetry and provocative art, she becomes estranged from the New York scene. Artists like Duchamp and Man Ray carefully cultivate the marketing of their work to curry favor with America’s capitalist elite. Elsa, by contrast, is passionately anti-capitalist. The price she pays is poverty.

Even for New York’s ‘avant-garde,’ this first New York Dadaist is too intense. In 1923, Elsa decides to return to Germany. She finds a shattered country. With no money to her name, she teeters on the brink of madness in a land full of madness, still reeling from the First World War.

One reason Duchamp may have left his “female friend” unnamed in his letter could be that, at the time of writing, America had declared war on Germany. In American newspapers, the name of a German general repeatedly appears: Von Freytag-Loringhoven. Censorship of mail may have prompted Duchamp not to mention Elsa by name. She had already been known for two years as the wife of a German prisoner of war. The American press wrote in 1915: “Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, without money in a strange city, her husband a prisoner of war somewhere in France, must pose as a model in the men’s class at the New York School of Applied Arts. Her husband is a lieutenant in a German regiment. His father is General Baron Freytag-Loringhoven on the German general staff.”

Elsa’s fortunes seem to improve when she moves to Paris. But then Wednesday, December 14, 1927, dawns—a cold, grim day. She falls asleep with the gas valve open. The next morning, she does not wake up. Her friend, writer Djuna Barnes, calls Elsa’s death “the result of a cruel joke taken too far” in her obituary.

Whether someone else was involved in her death remains unclear. Barnes asks Duchamp to curate Elsa’s estate. He agrees. Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, the creator of Fountain, is buried ten years after the artwork’s commotion in Père Lachaise, the famous cemetery for artists and creatives.

She Too

Schamberg’s photo of *God* was auctioned by Christie’s in 2011. The auction house estimated it at around $7,000. It ultimately sold for $390,000. The Philadelphia Museum of Art has since reluctantly acknowledged Elsa as co-author of *God*. But little more. A century later, Elsa still does not receive the credit she deserves—not for *God*, nor for *Fountain*. As her friend, American writer Emily Coleman, remembered her: “not as a saint or a madwoman, but as a genius, alone in the world, in despair.” Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven: marginalized and erased from art history. Yes—*she too*.