Late Greats

The new ‘hot young things’ of the art world

Could it be that female artists over 60 are the new ‘hot young things’ of the art world? With a slew of exhibitions and increased media attention focused on living female artists who received scant attention in their youth, it seems that these artists are finally getting their due.

People who make art and people who make it valuable spend a lot of time discussing the issue of what makes a work of art significant. What they don’t discuss as often or openly is what makes an artist standing before us in a gallery appear important. Or, even more the case in today’s quick-hit, first-impression-driven culture: What does a successful artist look like?

Siri Hustvedt’s last novel, The Blazing World, offers a particularly memorable take: ‘Anton Tisch looked right. He was tall, almost my height, a skinny kid in loose jeans with a significant nose and searching eyes that seemed unable to fix on anything for long, which gave him a distracted air that could be interpreted as a restless intelligence under the right circumstances.’ Later, he is described as a kindred spirit of Jeff Koons: a seeming boy genius who won’t – or can’t – speak in any depth about the impetus behind his work.

But readers know that’s just a façade: the exhibition that launches Tisch’s career was actually created by ‘Harry’ (Harriet) Burden, a sixty-something woman who is physically as well as intellectually intimidating. And in the narrative of the novel, the market experiment is a resounding success. When passed off as a man’s work, Burden’s psychologically loaded and visually layered artwork finally gets its due, resulting in sold-out New York shows, critical attention and posthumous museum surveys.

The novel gets at the rampant gender discrimination in the art world, the sort that feminist/activist groups from Guerrilla Girls to Pussy Galore and Gallery Tally have been vividly illustrating for many years.

Getting Their Due

There seems to be some promising, if hard to quantify, news for Burden and her real-life counterparts: a number of important women artists who have been actively showing in smaller venues are finally, in their 60s, 70s or even well into their 90s, receiving major museum retrospectives.

In the process they are beginning, slowly but stubbornly, to change the face of the successful contemporary artist, exposing that image of a lanky, attention-deficit-disorder-addled twenty-year-old man-boy as a blue-chip art-market fantasy.

The idea of the hot new artist taking the form of an older woman has even become subversive and fashionable in a way, featured in glossy magazines such as W Magazine and T, the style magazine of The New York Times. Here you can just imagine the middle-age editors of the youth-obsessed magazines feeling great relief as they find an antidote to all the attention that they themselves have lavished on hot young things, not unlike the way that French fashion brand Celine surprised the fashion world by using the American writer Joan Didion for its recent ad campaign by the German photographer Juergen Teller, transforming the 80-year-old writer, long a paragon of cool elegance, into an of-the-moment style icon.

The 68-year-old Canada-based artist Suzy Lake, whose early photographs and performances test boundaries of the self much like male contemporaries Chris Burden and Vito Acconci, received a proper retrospective at the Art Gallery of Ontario in 2014. The 74-year-old pioneering American artist Lynn Hershman Leeson also got what was billed as her ‘first comprehensive’ museum retrospective at the ZKM Museum of Contemporary Art in Karlsruhe Germany at the end of 2014. It showed her biggest projects, from the elaborate construction of an alter ego named Roberta Breitmore in the 1970s to her digital avatars of recent years.

LATE, LATE GREATS

Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun (1755-1842), an internationally famous court painter to Louis XIV and Marie-Antoinette in her day, received her first major exhibition at the Grand Palais in Paris 170 years after her death.

Sonia Delaunay (1885-1979) who cofounded with her husband, Robert Delaunay, the Orphism art movement, which was highly influential in the design world, was the first living female artist to have a retrospective exhibition at the Louvre, in 1964, when she was 79 years old.

Frida Kahlo (1907-1954) was only recognised by art historians and exhibited posthumously, starting in the 1970s.

Louise Bourgeois (1911-2010) now recognised as one of the key figures in modernism, received her first retrospective in 1982 at the MoMA in New York, at age 71.

Leonora Carrington (1917-2011) one of the early surrealist painters, received her first major retrospective in 2013, two years after her death, at the Irish Museum of Art, Dublin, followed by a retrospective at the Tate Liverpool in 2015.

ISA GENZKEN

‘Art should always be personal’

Isa Genzken, 2014

Arguably one of the most influential living female artists, the German artist Isa Genzken (born 1948) is the archetype of self-reinvention. While studying art history and philosophy at the University of Cologne, she took an art course at the Art Academy in Düsseldorf, where her classmates included Thomas Struth and Katharina Fritsch. Not long afterwards she met the German visual artist Gerhard Richter, whom she married in 1982. The relationship was one of mutual artistic influence, but ended in divorce in 1994.

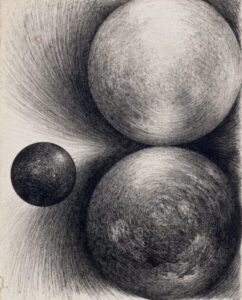

Her work has changed over the years. In the 1970s, she was known for colourful wooden ellipsoids; from 1997 onwards, she has made assemblages, which include objects ranging from consumer debris like toy dinosaurs to oyster shells.

Although she had several solo exhibitions in Europe, including at the Boijmans van Beuningen in Rotterdam (1989), her critical acclaim started to mount only in the early 2000s. She participated twice in the Venice Biennale (in 2002 and 2007), at Documenta 11 in Kassel in 2002, and was the subject of an exhibition at the Museum Ludwig in Cologne (2009). It wasn’t until 2013, at age 65, that she was recognised with a large-scale retrospective at New York’s MoMA. Now, the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam presents an extensive survey of her 40-year oeuvre.

Breakthrough: MoMA New York retrospective, 2013.

German artist Isa Genzken, who turned 67 in November, had her first comprehensive retrospective open at the Museum of Modern Art in 2013 and then travel to the MCA in Chicago and the Dallas Museum of Art. This winter, she has a survey at the Stedelijk that is being billed as the largest ever in the Netherlands, ranging from her early computer-generated abstract sculptures of the 1970s to her recent, and rather perplexing, sculptural tableaux.

The T magazine story, for its part, featured the extreme case of Cuban-born, New York-based minimalist painter Carmen Herrera. Now 100 years old, she is working on a major solo show at the Whitney Museum of American Art to take place this year that will feature her hard-edged, restricted-palette geometric painting from a forty-year period. The show comes on the heels of a retrospective exhibition that ran in 2009 at the nonprofit IKON Gallery in Birmingham, England, and in 2010 at the Pfalzgalerie Museum in Kaiserslautern, Germany.

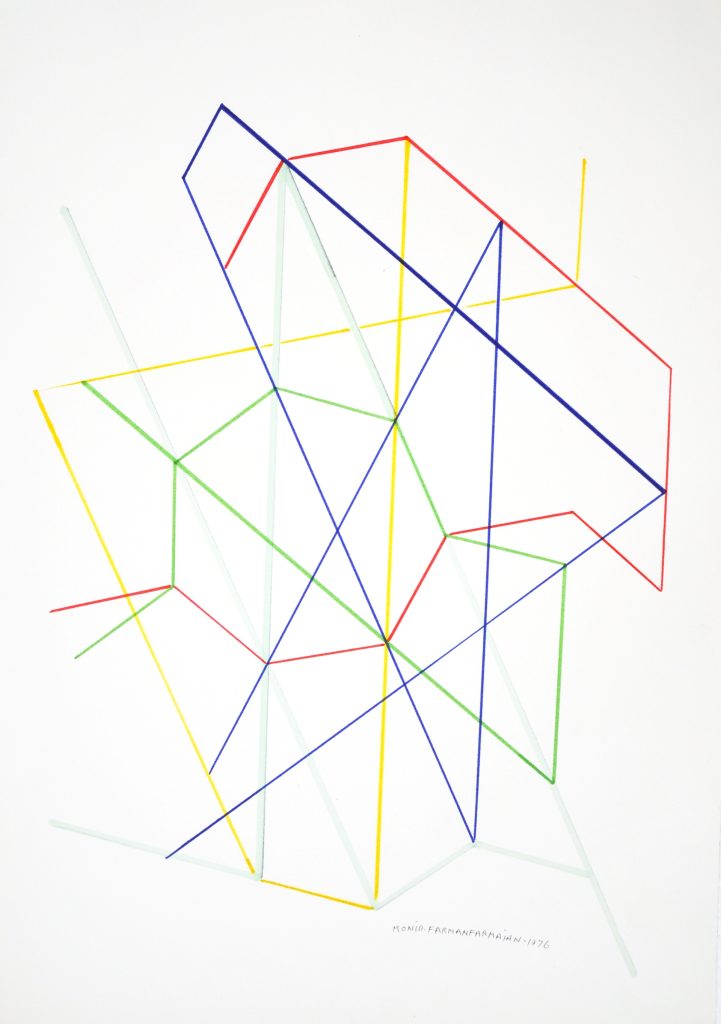

The same article also gave a spread to 91-year-old Iranian artist Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian, who creates intricate three-dimensional panels using mirrors and stucco that reference the history of Persian design. Once again based in Iran after a 26-year exile triggered by the Islamic Revolution of 1979, she recently received her first large retrospective, which opened in 2014 at the Serralves Museum in Portugal and reached the Guggenheim in New York in spring 2015.

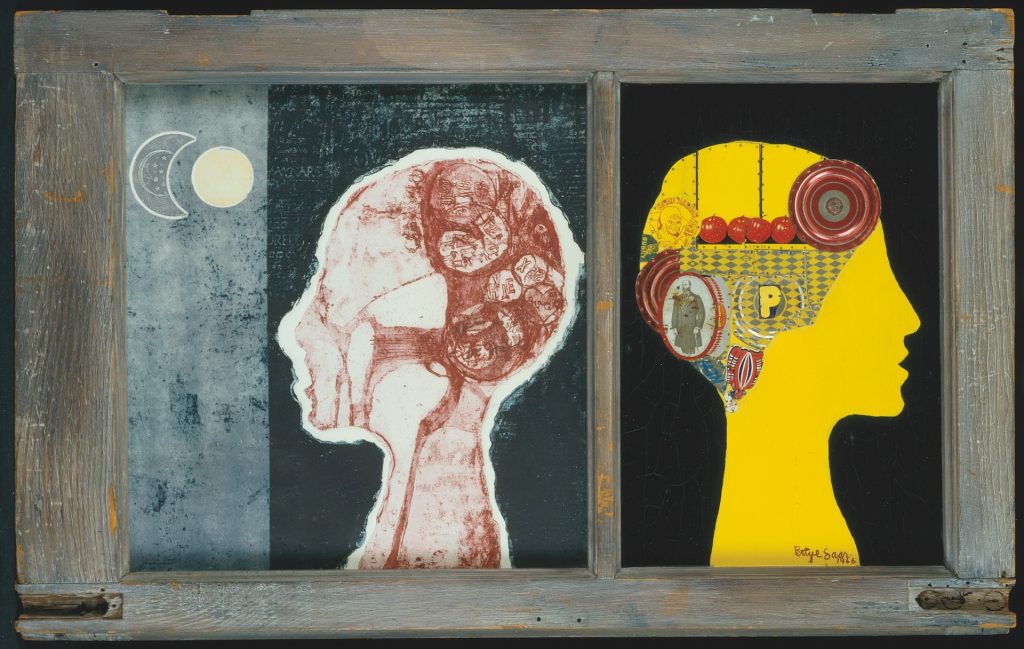

They could have considered Betye Saar as well, the 89-year-old Los Angeles-based American artist who has broadened the assemblage tradition of Joseph Cornell by incorporating in her boxes (also bird cages and other apparati) found objects that have cultural, racial and mystical narratives embedded in them. ‘I walk looking down all the time. I go to flea markets and garage sales… materials give me my ideas’, she once told an interviewer.

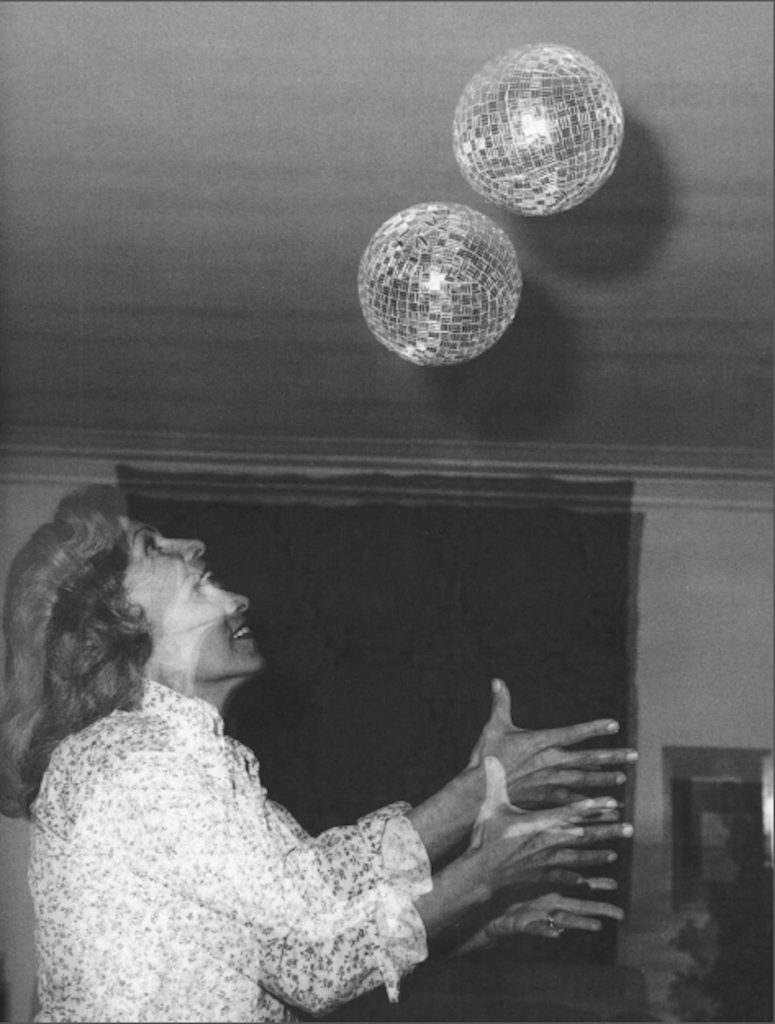

A decade ago, she had a retrospective focusing on her use of photography within the assemblages tour the United States. Now, she is getting more international attention, with a different retrospective given the spirited title Still Tickin’, spanning six decades of her work, that ended in November at the Museum Het Domein in Sittard, the Netherlands, and moves to the Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art in Arizona from 30 January through 1 May.

Heroic Painter Narratives

Curious about what’s motivating this trend, I made a list of the curators who have championed these artists to see if they are of the same generations and perhaps finally in positions of power that would enable them to devote serious museum space to artists of their choice. But that by and large isn’t the case.

As it turns out, it’s thirty-something or forty-something curators, men and women, who are giving older women artists their due, whether consciously driven by a desire for diversity or somehow free from the blinders of old white-male-worship. The Saar exhibition was curated by 41-year-old Roel Arkesteijn, the curator of contemporary art at Museum Het Domein, Sittard, while the Art Gallery of Ontario show Suzy Lake was organised by two forty- something associate curators: Georgiana Uhlyarik and Sophie Hackett. (Lake’s catalogue also had a guest essay by one of the most famous teenage writers today, 19-year-old Rookie magazine founder Tavi Gevinson.)

In short, there seems to be a younger generation of art historians who are helping to give more established artists their fame. It may be that the growing emphasis on race and gender in liberal arts study programmes at universities has influenced the way young curators think and operate. It could also be the result of an overall gender shift in the art world (according to ARTnews, women in 2005 ran 32 percent of the museums in the United States but they now run 42.6 percent). It might also be that with the extraordinary rise of the contemporary art market comes greater opportunities for a broader range of artists, whether they fit our heroic-painter narratives or not. This is admittedly an optimistic take.

Siri Hustvedt also offered a slightly more cynical explanation for why some artists who have been working for many decades don’t get recognition until later: a deep cultural prejudice against intelligence and serious ambitions in young (especially attractive) women. In a talk at the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art at the Brooklyn Museum, Hustvedt asked her audience to imagine being at a party where you spot ‘this gorgeous young woman in a low-cut dress. Then you are told she is working on her second post-doc in molecular biology at Rockefeller University. How surprised are you?’

‘It’s one of the reason that older women artists, writers, musicians, conductors, whatever are granted a position in a way that younger women aren’t’, she said. ‘You get wrinkles, you sag, and then it’s okay to respect you.’

Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian

‘The reflections, seem to liquefy you, for you’re a part of the art piece. Your own picture, your own face, your own clothing – you’re the connection: it is the mix of human being, reflection and artwork’

Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian in conversation with Hans Ulrich Obrist, 2008-2010

Living and navigating between two cultures, Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian (born 1924), derived her artistic language from her native Iran whilst living in New York. Travelling to America in the 1940s to study fashion illustration at the Parsons New School of Design, Farmanfarmaian rapidly found herself amidst the New York avant garde. She worked as a fashion illustrator, collaborating with Andy Warhol on windows for the Bonwit Teller department store and became part of the Greenwich Village scene, befriending such artists as Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning and Milton Avery.

Perhaps paradoxically, living in New York renewed her interest in traditional Iranian craftsmanship. In 1957 she returned to Iran. She created mirror mosaics, simple flower paintings and monotype paintings on glass and canvas. At the same time she collected local art, panelled Safavid-era doors and reverse-glass paintings. All of these possessions, including her own work, were confiscated, sold or destroyed in 1979 during the Islamic Revolution. She fled again to New York and remained there for 26 years.

In 1958 she represented Iran at the Venice Biennale for the first time. At the age of 91, she had her first major success with Infinite Possibility: Mirror Works and Drawings, at the Serralves Museum, Porto and the Guggenheim in New York in 2014/2015. At the same time, she was the subject of the documentary Monir by Bahman Kiarostami (2014).

Breakthrough: Infinite Possibility: Mirror Works and Drawings, Serralves Museum, Porto, to and Guggenheim in New York in 2014/2015.

Yet whatever the reasons, it must be said that these are still isolated examples and the numbers are still stacked against artists who happen to be women. As The New York Times art critic Roberta Smith wrote about Genzken’s MoMA show in 2013: ‘It counters the season’s trend of big retrospectives devoted to male artists and increases from a paltry four to a still paltry five the number of full-dress sixth-floor retrospectives the Modern has bestowed upon women since taking back its expanded building nine years ago’.

An article by the Sackler Center’s founding curator Maura Reilly, ‘Taking the Measure of Sexism’ in the May 2015 issue of ARTnews, a manifesto of sorts that sparked great debate and dialogue, ultimately painted a bleak picture of the proportion of women artists included in international biennials and museum collections over recent years. After collating a lot of data, she concluded, ‘women artists are in a far better position today’ than they were a half a century ago, ‘but inequality persists’.

Nowhere are the roadblocks more visible than in the marketplace, where it’s rare for a woman to ever break into the top ten lists for most expensive living artists. One list published on Artnet.com last year put Cady Noland at number 7 because of the $9.8 million sale of her Bluewald (1989) at Christie’s in May, though the number-1 ranked Jeff Koons brought at his height $58.4 million.

If there’s any benefit to not being discovered commercially earlier, it could be a willingness to venture beyond one signature (read: marketable) form of art, either by working within the deliberate loose traditions of assemblage, installation art and performance or by moving rather fluidly from one medium to another.

A ‘boy genius’ like Koons is pressured in various ways by the market to stick with his successful formula: in this case, big, shiny baubles. As much as they might not recommend it or desire it for obvious reasons, artists who are ‘discovered’ later in life (and not rewarded financially to the same degree anyway) might have a leg up when it comes to a willingness to follow their instincts into any form.

Though careful not to overplay her import, Roberta Smith for example called Genzken ‘one of a host of women who began in the late 1980s to view assemblage – the piecing of disparate parts into unruly wholes – as an expansive, unbounded, antiheroic mode that could be simultaneously personal, political and formal’.

I saw this firsthand when I curated a small exhibition in 2007 for the Santa Monica Museum of Art, Identity Theft, which featured role-playing projects by Hershman Leeson, Lake and another conceptual-leaning artist, Eleanor Antin, made in the 1970s before Cindy Sherman created her landmark Untitled Film Stills. But more than a photography show, this exhibition included a dizzying number of forms: recorded and documented performance, drawings, narrative texts, videos, collage, photo-collage, paper-doll cut-outs, costumes, letters, book pages and even a comic book about Roberta’s adventures. The formal inventiveness was striking.

Come to think of it, ‘identity theft’ is also an accurate way to describe the quasi-criminal and wonderfully provocative actions of Harry Burden, Siri Hustvedt’s fictional hero (heroine sounds inadequate in this context) in The Blazing World. And Burden’s artworks too are hard-to-pin-down, taking the form of messy installations and oversized dolls, culminating in one giant naked, pregnant female doll whose head is filled with miniature wax figures singing, dancing, writing and making art. As Hustvedt writes, ‘This woman had worlds inside her.’

BETYE SAAR

‘It’s a way of delving into the past and reaching into the future simultaneously’

Betye Saar, 1998

African-American artist Betye Saar (born 1926) combines found objects with caricaturist ‘black collectibles’ in provocative assemblages and collages that explore the texture of black history and the nature of femininity. Growing up in Pasadena, California, in the 1930s, she often visited her grandmother in Watts, where she came in contact with the artist Simon Rodia, who collected debris to construct and decorate his famous Watts Towers. In 1967, after seeing an exhibition by Joseph Cornell, she really began to make assemblages.

Her work has been exhibited throughout the United States, although often in small venues. Saar also curated exhibitions such as Black Mirror at Womanspace in 1973, devoted to black women artists, it was an instance in which the paradoxical nature of feminism became clear, hardly any white women artists would attend the exhibition’s activities and events.

In the United States she has had significant solo exhibitions, in 1975 her work was exhibited at the Whitney Museum for American Art and in 1984 at the Museum for Contemporary Art in Los Angeles. National acclaim was only followed up by international recognition in 2015 with the solo exhibition, Betye Saar: Still Tickin’, which was first on view at the Museum Het Domein in Sittard, the Netherlands.

Breakthrough: 1975, exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art.

Carmen Herrera

Havana-born artist Carmen Herrera had her first solo show in 1998 at the age of 83, and turned 100 years old in 2015; she’s now the subject of a new documentary film, The 100 Years Show, and is the focus of an upcoming autumn 2016 retrospective featuring fifty works from over four decades at the Whitney Museum of American Art. This relatively recent attention for her work comes as a surprise to the artist, who has been working quietly on her own for more than half a century.

Herrera moved from Cuba to the US in 1939 with her husband, and after WWII the couple spent several years in Paris. There, she discovered her pictorial style – early pre-minimalist, abstraction – and exhibited alongside artists such as Josef Albers, Jean Arp and Sonia Delaunay. The couple returned to New York in 1954 and it wasn’t until 1998 that she had her first solo exhibition, at the El Museo del Barrio in Harlem. She sold her first artwork in 2004, and later was collected by the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington DC and the Tatwe Modern in London.

‘I was amazed when my first painting sold,’ she says in the new documentary, ‘I still am amazed.’

Breakthrough: Solo exhibition at the El Museo del Barrio, New York, 1998.