An island of one’s own

An alternative history of women

This is an alternative history of women – how they found and lost liberty – set in the cold cluster of islands between the Atlantic and the North Sea. For See All This, Alice Albinia explored female power and female potential. She reaches deep into the matriarchal past to ask how radical we might be, if given the chance.

Patriarchy is a recent human invention; it is not our natural state. If you look far enough back into recorded human history, into enough different places, a pattern becomes clear: before written words encoded male dominance in the very language and texture of holy books, law codes and epics, a different social structure prevailed on earth. It made perfect sense to treasure and worship women for their particular gift of procreation: one of the most important and precious functions of life on earth for early human societies. Humans’ seasonal rhythm, their cultural construct, seems to have revolved around safeguarding this process.

The subsequent cult of male worship — the most successful of our world religions — crossed cultures and class, floating men to the top of the social hierarchy and keeping women as their subservient labour force. Since the populations of men and women are equal, however, it was only ever a mind trick (as with all hegemonies). With each new god or king, the pattern deepened, acquiring the patina of age and the authority of tradition. It takes only a few generations for societies to acquire such things as the generic masculine, whereby anybody hearing the word ‘judge’, or ‘mayor’, or ‘prime minister’ automatically thinks of a man.

Echoes of the earlier time remained in the cultural consciousness, however. Throughout the ensuing history of patriarchal dominance, stubborn golden flashes of an alternative way of living glint through the suffocating prevalence of male egos like phosphorescence in a bog. In ancient India, stories were told of a faraway land in the northern mountains where women ruled. In ancient Europe, these female holy lands were situated on islands away from the mainland — the ancient Greeks write about this, as do the Romans, and subsequently British island dwellers themselves. In place of later medieval convents or beguinages, ancient and medieval writers from across Europe gave independent women islands where they were free to control the weather, predict the future and live without men, or with them but in complete equality.

I realised this when I began researching my forthcoming book about Britain, The Britannias. After a certain point I became depressed and shocked by the number of male stories and histories I was reading and digesting. But I knew from my research into the early history of India that female counter-currents always exist, if you can only find them. Women always tell stories; men always have mothers; tales of female leadership and freedom will always out. This is what I discovered in the story of Britain: a continuous thread of female emancipation that weaves its way, undeterred, through the most egregiously male-fixated of ages.

From at least the time of Strabo, writing in around 7 BC, Britain was othered as a frozen land beyond the outer ocean — a place so barbaric that its women were chosen as leaders and its small islands were centres of goddess cults or inhabited by prophetesses who controlled the weather. Ancient Greek writers, colonial-era Romans, medieval Irish poets, Renaissance dramatists, Restoration travel writers: all in turn were tantalised by the intoxicating idea of islands (especially remote northern ones) ruled by women — witches, goddesses or prophetesses who controlled the weather. This could be why English is the only Indo-European language in which the word for a female ruler (queen, from Old English cwen) is not derived from the male word (king) and why it was in Britain, in more recent times, that women first got the vote (on the Isle of Man, in 1881).

Islands have a quality of apartness that makes them the ideal loaction for experimentation and novelty.

Both The Britannias and my accompanying novel Cwen take inspiration from the first indigenous writing about female freedom in Britain: a seventh-century secular Irish poem about the islands of women in the western ocean, a tale that, tantalisingly, is not only repeated in different iterations down the centuries, but is itself a reincarnation of stories already told of British women for hundreds of years before that.

Islands themselves have a quality of apartness that makes them the ideal location for experimentation and novelty. They can also be ‘enclosed, inward looking’ — as Cornelia Parker wrote of Brexit Britain in Island, the concluding installation of her major Tate Britain retrospective. But Strabo and his cohorts were right: something unusual happens to the mind whenever you set foot on an island. The close interaction between the elements of water, earth, fire, air — and women — disrupts the usual pattern; in the dance of these elements, some harmony is restored. These are the communications I am curious to explore.

Water

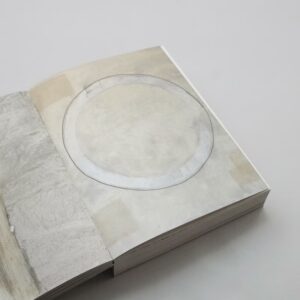

The island women surround themselves with shimmering liquid; it encircles their island like a golden torc. The seas are rough; they are bountiful. They create a necessary distance: the water keeps their thoughts in and predators out. It allows them the freedom to be together, and alone with their sex. It comes to seem primordial; entire communities cooperate to make island rituals honouring the mystery of women’s singular fecundity of body and mind. A sacred relationship is perceived between the silver orb of the moon, the tides, the rise and fall of women’s blood; between the goddess warmth of the sun, the swell of a belly, and the ripening of heads of corn. The desire to keep these liquid crucibles of life safe within the bounds of water grows in importance. Even before myths are constructed — of a mother and her lost daughter, seasons turning, and deathly quests for freedom deep within the glowing bowels of the earth—monuments are built, honouring the circles that women make and are, channelling the complimentary power of sun and moon, enshrining their freedom.

Writing arrives in the islands, and the very earliest commentary — in languages foreign and remote — expostulates on the freedom that being encircled by water allows these women. Stories are told of island prophetesses who predict the future, control the climate and hold the rattlebag of storms tight in their hands.

When Romans invade with their swords and their pens, patriarchal history begins to be written. Female independence is traduced. Women stand in the front line of the defence of the sacred island of Anglesey, off the north coast of Wales, watching Roman soldiers crossing the sacred boundary. The Romans cut down the island’s groves of sacred oak and build forts on the ashes.

As before, something survives. Already, stories have come from the south, telling of islands ruled by female magic (Calypso and Circe). These intermingle with tales filtering down from the north, telling of islands ruled by feminist notions. Then an amazing thing happens — the idea of islands ruled by women jumps from foreign-told travelogues to indigenous invocations. In early medieval Welsh and Irish poetry, local female independence finds new expression.

Like sunshine filtering down through a canopy of leaves, ancient ritual repurposed by early exotica inflects the way Britons speak of their island women. Whispers circulate about what islands do to women, and what women do to islands. Water is freedom, as I found myself, when I crossed the sea.

— And only now do I realise how unbound I was, once; what a world of time I had. Now my daughters are always here, in the room, on the island, in my mind, on the page. They populate my thoughts.

Earth

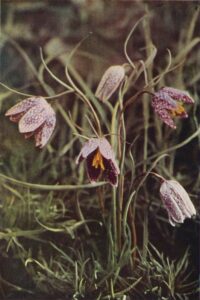

From within the sacred orb of water comes the healing medicine of herbs, roots and leaves — syrupy resins and rising saps watched and tended, plucked and dried, ground and distilled, things bitter and soothing, dangerous and sweet.

After months at sea, approaching land smells strong. Earth and its cultivation have always been important in remote island places. The careful curation of human waste once contributed to the luxuriance of life. Faeces, household detritus, food, animal excrement, was golden matter, used for insulation and sacred deposition. Up to medieval times in Europe, the midden — the stockpile of household waste — was mentioned in marriage contracts and wills. I grew up next to a lawn called the Midden: earth’s human wealth, the richness of all that could not be ingested, or had been digested, under my toes.

'Even Shakespeare can't help depriving his island witch of her land and power'

For eyes and fingers and noses that understood the rhythms of the tides, the waning and waxing of the moon, extracting the earth’s quintessence was a matter of trial and error, deduction and logic. An ancient association between island women and the magic of earth’s healing bubbles up from the macho underbelly of Thomas Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur (1485) like fragrant burps of watermint. The king’s court is the focus of Arthurian romances but in the hinterland are many powerful independent women: the lake gynocracy, ruled by the Lady of the Lake; Arthur’s half-sister, Morgan le Fay (‘the fairy’); the Queen of the Wasteland. It is they who ferry Arthur away across the water at the end of his life, for healing. It is they who inaugurate his reign with the lake- born sword that is the secret of his prowess.

Earth medicine women are not always lucky. Male hysteria sometimes has their wombs wandering around their bodies. Laws are passed, legislating the murder of old healers. Ancient knowledge is lost, or driven back underground. Even Shakespeare, who admired the logic of islands and was preoccupied with the logic of women, can’t help depriving his island witch of her land and power in The Tempest. Lore-death eviscerates a culture. But again, something survives. In Scotland, Gaelic preserved all the old magic and incantations even into the nineteenth century.

— On the train out of Glasgow, towards my writing retreat at Breachacha on the Isle of Coll, I sit down opposite a forester, older than me, reading a book I recognise. We talk all the way to Oban. He tells me that there are foresters in that country who even now refuse to cut down the rowan, because it is the fairy tree.

FIRE

The Scottish anthropologist James Frazer thought that Gaelic culture’s survival trick was to clothe the old ‘heathen’ goddesses ‘in a threadbare Christian cloak’. St Bridget, he wrote, was the fertility goddess — of fire and crops.

Once, the return of the fire orb in the sky cannot have seemed a certainty — it was a privilege that humans earned, rather than their right. Propitiating the sun with worship of its complementary female qualities on earth was a huge undertaking and required organisation and effort, as well as mathematical precision. Some of the most magnificent Neolithic engineering is found on the islands of Orkney, in the very north of Britain, where, at the darkest point of the year, the sunset is channelled like sperm into monumental stone structures to fill womb chambers with its radiance.

Photography is fire-writing, says the Orcadian photographer Rebecca Marr. She works with seaweed and light in her darkroom, drawing on the investigations of Anna Atkins, whose 1843 collection of cyanotypes, Photographs of British Algae, was the first photographic book ever published. Botany, Marr says, was seen as a natural pursuit for Victorian women, concerned as it is with God’s creation. The seashore, in particular, allowed them a great degree of freedom. ‘They could hitch up their skirts, walk along slippy rocks, all within confines of what was acceptable.’ Women were also associated with seaweed classification, as Robert K Grenville made clear in Algae Britannica (1830) when he thanked ‘my fair and intelligent countrywomen — to them we are indebted for much of what we know on the subject’.

When I lived in Orkney, in those dark/light islands, I too became obsessed with seaweed, through which I swam most mornings, as well as with the passage of the sun through the sky. I lived on the hilly island of Hoy — the dark mass of stone behind which the sun sank at the winter solstice — and all weathers swirled around my house. Every storm seemed a new form of art painted or etched or scribbled in the sky. I kept a stash of blueprint paper in my desk, so that when the sun came out I could rush the children outdoors and create sharp blue sunlines with the seaweed, shells, daisies, grasses, feathers and stones we picked up on the beach. Depending on the patience of the children, or the impatience of the wind, we might manage to make images of those moments, drawn in solar fire.

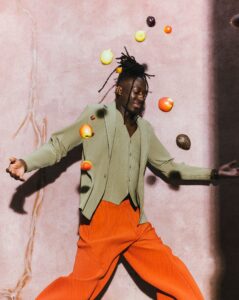

— With the Peruvian-French photographer Miguel Coquis, I work on a pinhole self-portrait. He has me turn, thrice, holding the box at arm’s length. We develop the film in his darkroom, bathing it in a tray of fluid, as I remember the tides lapping at my feet in Orkney. In darkness, we lift the film out of the tray, then take it outside. In the sky behind my head, the sun appears as a single streak of fire, as if I am one of Pomponius Mela’s island prophetesses making lightning.

AIR

An ‘Airy word’: that’s what Shakespeare calls speech in Romeo and Juliet — a metaphysical product of our bodies that comes out formed into language on the heat of our breath. ‘Air’ is the name for a tune, too — as if songs were trapped deep inside us, looking for a means of escape. If we could smell them, maybe they would tell of our hidden-most emotions — all the love and loss and longing of our bodies and minds. The acoustics of our bodies/their monuments is one of the ways we can approach our distant ancestors. Their bodies/ours, their monuments, their/our movement through them traverse this historical dissonance.

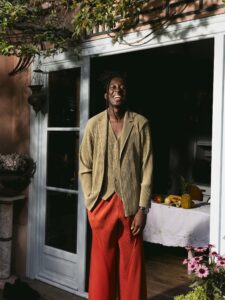

I made friends with the late Orcadian voice coach Kristin Linklater while experimenting with the acoustic of Orkney’s Neolithic monuments. In the 1990s, Kristin ran the world’s first all-female Shakespeare company, in Boston, but in her latter years she returned to Orkney to work with actors and singers, helping them find their voice, literally and metaphorically. Early one summer morning, we met at the Neolithic chambered cairn of Maeshowe — Kristin, ten of her students, the Edinburgh band Sink, my baby and I — to chant. It was Kristin who pointed out to me the monument’s womb shape.

Afterwards, I asked her, ‘What did you hear as we sang?’

‘The music of the spheres,’ she said.

Later, she came to visit me on the island of Hoy. We sat inside the Neolithic rockcarved chamber known as the Dwarfie Stone — which has a rich and resonant acoustic; a healing sound-bath, Sink’s violinist and singer had assured me — and she taught me the Selkie song. Sung in seallanguage, it tells of the love of a mortal woman for her mystical seaborne lover.

The voice is a portable instrument, as are songs, and Scotland’s islands, which lie in the midst of the seaways, have long been associated with musical innovation. New music is always being made on the islands — such as the album, Songs of Separation, recorded in 2016 on the isle of Eigg in English, Gaelic and even Norn (the now-extinct Norse language of Orkney and Shetland) by ten female musicians.

— But it is on Tiree, a nearby island, that, thanks to a man, I finally find the female acoustic of the Neolithic. Down by the sea, I tap a gigantic breast-shaped stone known as the Ringing Stone with a pebble. The stone’s Neolithic voice rings out: clear and metallic. Carved with cup marks, the boulder is believed by archaeologists to have been a site of Neolithic female reverence. At high tide, the Ringing Stone is surrounded by sea, an island off an island off an island.

VOID

On the neighbouring island of Coll is a large boulder, an erratic, magically deposited on a hill there by a glacier long before human time and held forever after by three smaller stones, where it balances to this day. Transported by ice, supported by earth, warmed by the sun, the stone encapsulates, in its relationship with the surrounding air, a truth about women: they need their own space. Where the stone has come to rest, a tiny space exists between it and the receiving earth, through which women are supposed to wriggle — according to local folklore — to call down the mysterious blessing of a child or to prove that they are not already with child. This complicated arrangement is called the Queen Stone.

If women have been suppressed and compressed down the centuries by their lack of independent space, then logically the apartness of women’s early island communities, imaginary or not, must have been among their greatest virtues.

At school I wrote about To the Lighthouse, Virginia Woolf’s 1927 novel of grief and time passing/women and creation. It is set on the Hebridean island of Skye. Only years later (now) do I notice that, immediately after finishing it, Woolf began writing about women’s need for independent space in A Room of One’s Own.

An island of one’s own. The earth-magic of witches and healers was also that: the finding of mental space. Chanting, singing, breath work; the alchemy of fire; the ingestion of carefully prepared plants with their varying levels of toxicity — all had the potential to open up the mind-space which daily life denied many women. Witchery was this, perhaps: a trick to overcome life’s limitations.

The best thing I dug out of the Orcadian midden where I was excavating as writer-in-residence in the sacred Neolithic island complex of the Ness of Brodgar was an incense burner. Neolithic pilgrims loved to breathe the fumes of hemp and poppy — they seem to have been interested in metamorphosis — just as they deployed the liminal properties of standing waves and the transforming glitter of water over rock in their rituals.

The discovery made me pause. The cultural lacuna at the heart of the West, which has contributed to women’s subsequent suppression, was possibly created as black- clothed druid women on the island of Anglesey called down curses on the Romans, singing the death knell of an epoch. During the long centuries of its colonialisation of the global south and east, the West greedily gathered up other cultures’ spaces, just as it now seeks out their indigenous medicines and rituals. What does a culture without indigenous space-ritual look like? It looks Roman: patriarchal, centre-dominated, with a homogenous aesthetic exported across the seas. It looks mainland, mainstream, North American, European, Western.

Women, tending the hearth-fires, whispering spells and prayers over their newborns, guarding the mother tongues that written laws set out to erase, were some of the safest keepers of residual lore. Peripheral island women were the safest of all. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, when song collectors began travelling through the Gaelic areas of Scotland, it was out to the islands that they went. There, only just before it was too late, they found ancient pagan incantations, cradle and hearth songs, and indigenous plant lore long-lost elsewhere.

— In my novel Cwen I wrote about this. And one day, for sure, I will do it for real. Take an island, carve a boulder with cup marks, sing, dance, gather indigenous plants — and witness the transformations, as womenscapes are born in our minds.